They’ve all told a story on Jackanory!

The list of celebrities and British icons to appear on the kids’ show is phenomenal, and that probably says it all about a programme that has touched many generations of Britons.

December 13 this year marks half a century since it all began, and it’s safe to say that Jackanory inspired millions of us to take up reading.

Yes, we all had books thrust at us by schoolteachers, but only Jackanory had the power to make reading seem like the greatest thing ever.

It was the brainchild of Anna Home, Molly Cox and Joy Whitby, but they had no idea that when it hit the small screen, it would last well over 3,500 episodes.

Born in the summer of 1930, Joy studied History at Oxford before working at a Delinquency Clinic, later joining the BBC as a studio manager.

In charge of coming up with sound effects for radio dramas, she worked her way up to producer, and took over Listen With Mother, another children’s telly classic.

In her other work on Watch With Mother and Play School, she always stressed the importance of presenters talking straight to camera, treating every child viewer as an individual.

And there was always subtle learning along the way, something Jackanory was brilliant at.

From ’65 onwards, as it immediately grabbed a vast young audience, the Beeb treated Jackanory with a philosophy of: “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

10 childhood school and playground games no-one born after 2000 will have played – click here to read more

Its winning format would stay the same for many years, and it just kept working — simply get a well-known actor or actress to sit in a comfy armchair and read!

Children’s stories, folk tales, Winnie the Pooh, as long as it grabbed the young ones, it was worthy of a slot on the show.

Specially-commissioned drawings to go with the words filled our imaginations, with each book usually lasting Monday to Friday, split into five quarter-hour episodes.

Come to think of it, perhaps this is why many of us still have an attention span of about 15 minutes, but at least it got us reading!

Helena Bonham Carter, Tom Baker, Kathy Burke, Brian Cant, Bernard Cribbins and Judi Dench all jumped at the chance to read from that famous chair.

But it’s fair to say getting Prince Charles to read from his own work, The Old Man Of Lochnagar, was quite a scoop!

Charles appeared in 1984, and it remains a unique moment in royal history and in many an adult’s memories.

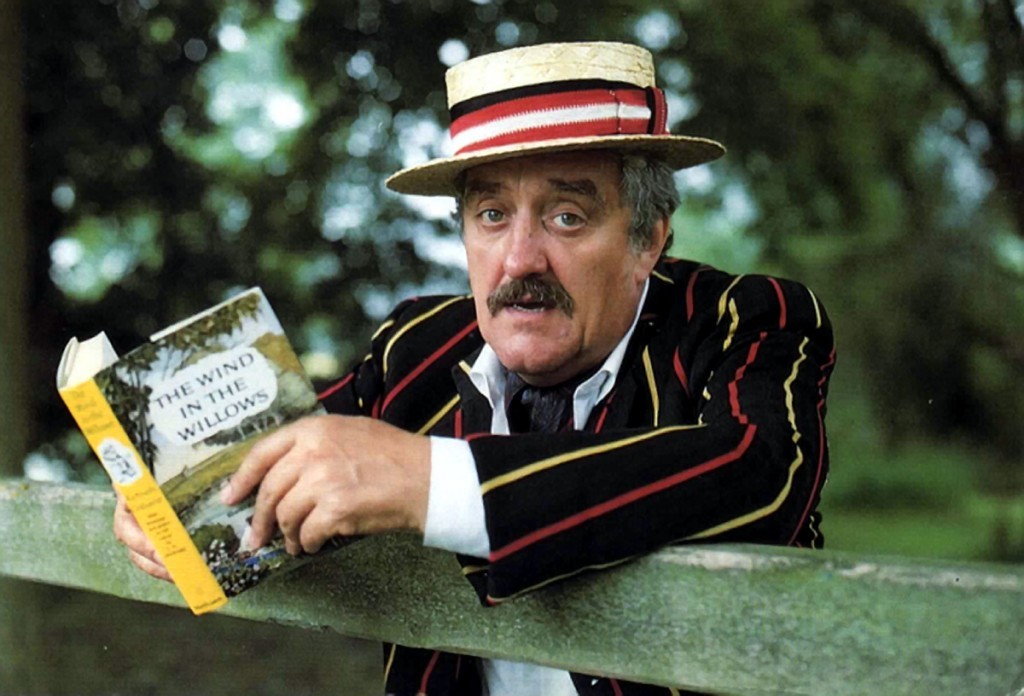

Bernard Cribbins appeared on multiple Jackanories, reading several tales from Roald Dahl, Lewis Carroll and JRR Tolkien.

He made more appearances than anyone else, in fact, racking up more than 100 readings, and he didn’t do too badly as the narrator of The Wombles, either.

Tufty in the 1960s road safety films was his, too, doubtless helped by the fact that British children knew his voice so well and always listened carefully when he spoke.

Even today, almost two decades after its final BBC appearance, folk of a certain vintage will mutter: “Jackanory, Jackanory” if they reckon someone is being less than truthful!

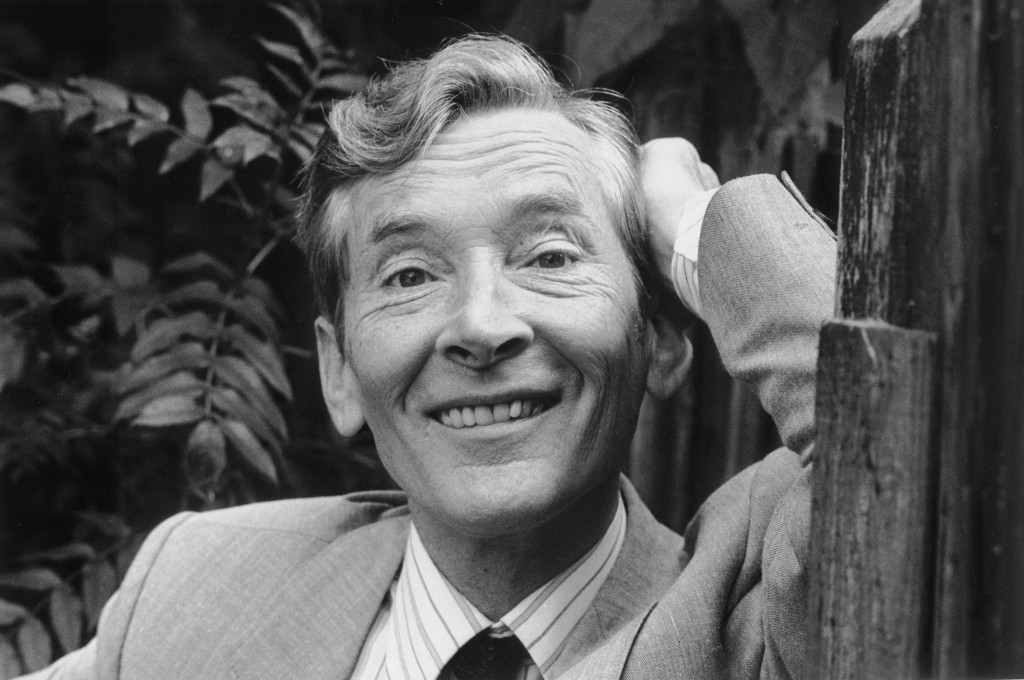

It seems bizarre, now, that Kenneth Williams was the second most-prolific Jackanory star.

Better known before that for his bawdy Carry On appearances, Williams would manage 69 stints on Jackanory — like many who tried it, he loved the experience.

Many a veteran actor has since revealed that it was the dream job — it took a mere half-day’s rehearsal before churning out a week’s worth, and no memorising as it was all done on autocue.

Williams thrived on his amazing relationship with kids — they loved his crazy face-pulling and the way he could bend and contort words, turning the language into an elastic new lingo.

A deeply-insecure man, he loved the fact they seemed to love him and demanded nothing except to please read something else tomorrow, and the day after, and the day after that.

David Benson was a young ’un in 1975, who sent his own little tale, Rag And Bone Man, into the Beeb as part of a competition.

When it won, he asked for it to be read by Kenneth, and many years later, he celebrated the memory when it became a full-blown stage show.

He turned the whole thing into a Kenneth Williams tribute.

Jackanory, and especially one of the Williams or Cribbins variety, meant a lot to kids, just as Joy Whitby had envisaged.

Williams’ readings were hilarious and spot-on, they even released them on cassette.

All the more incredible when you learn that Kenneth almost turned down the first offer of a Jackanory, worried they’d make him wear a hat!

He hated the things, and thought a hat would look rather daft on someone reading on a comfy chair.

Hats off to whoever decided no headwear was required.

From Tolstoy to Oscar Wilde, Gulliver’s Travels to Mary Poppins, the viewing audience were treated to childish escapism and some stories with a serious meaning.

Unknown to them, they were being secretly turned into a nation of bookworms, and many an English teacher has claimed Jackanory was a great help in making kids more aware of the power of the pen.

There are said to be few of the old shows left on tape, unless folk out there recorded them on hand-held cameras.

Many people did record their favourite TV shows this way, so we shouldn’t give up hope of any repeats just yet.

And if they uncover some of the many, many classics . . . now, that would be a very happy ending.

It all began in a log cabin!

JACKANORY was thought up in the unlikeliest of surroundings.

The show’s production team were on holiday in a traditional log cabin in one of Scotland’s more-remote regions, so the idea was quite apt.

With not a lot to do but sit and listen to each other telling stories, it just hit them like a lightbulb going on!

It took its name from an old nursery rhyme: “I’ll tell you a story about Jackanory, And now my story’s begun, I’ll tell you another about Jack and his brother, and now my story’s done.”

Anna Home, the first producer, revealed in her book Into The Box Of Delights that the word Jackanory once referred to political protest songs.

She joked that it had been disappointing to never receive any letters, accusing her of giving British kids any political prejudice or bias!

The very first Jackanory was read by English actor Lee Montague, who did it sitting on a white wrought-iron bench, next to a table bearing a jar of bulrushes.

Incredibly, it got criticism as it might put kids off reading, when they could just sit in front of the telly and watch someone else read for them.

Fast forward all these years, and they moan that kids are too busy watching telly to read at all!

Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which was repeated, was voted the viewers’ favourite in a 20th anniversary poll.

Rik wasn’t so marvellous

THE late, great actress Wendy Hiller was one of the unusual ones on Jackanory… she refused to use the autocue!

While many of the show’s readers were quite content to read from a small screen, Wendy was too short-sighted to read Little Grey Rabbit that way.

Her solution was to have the words, in extra-large type, pasted into a book. As a veteran of countless movies from the 1930s through to the 1990s, she was quite used to memorising large chunks of text, too.

Another much-missed star from a more recent era, Rik Mayall, caused a storm with his wild and wacky reading of the Roald Dahl story George’s Marvellous Medicine.

The tale of a young boy’s attempts to get rid of his granny, the BBC was inundated with mail, claiming both Rik’s presentation and the story were dangerous and offensive.

Cheap to make and with regular audiences of three million and upwards, the show would outlast many other series, with only minor adjustments through the decades.

Props appeared, some good, some pretty amateurish, along with drawings and the like, and there was also Jackanory Playhouse, a series of plays based on the scripts.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe