IT was shortly before 4.25 on the afternoon of Wednesday, May 31, 1916, and on board the battlecruiser HMS Queen Mary two shipmates were having a cheerful chat.

Midshipmen Archibald Dickson and Jocelyn Storey were stationed in ‘Q’ turret – Dickson in the ‘silent cabinet’ with the range clocks and Storey in the gunhouse.

Although he was only 16 Dickson, from Edinburgh, appeared happy and calm as he and his pal shared a joke.

Suddenly the order came through. “ACTION!”

Doors were slammed shut as a second order to load the guns was issued, and that was the last Storey saw of his young friend.

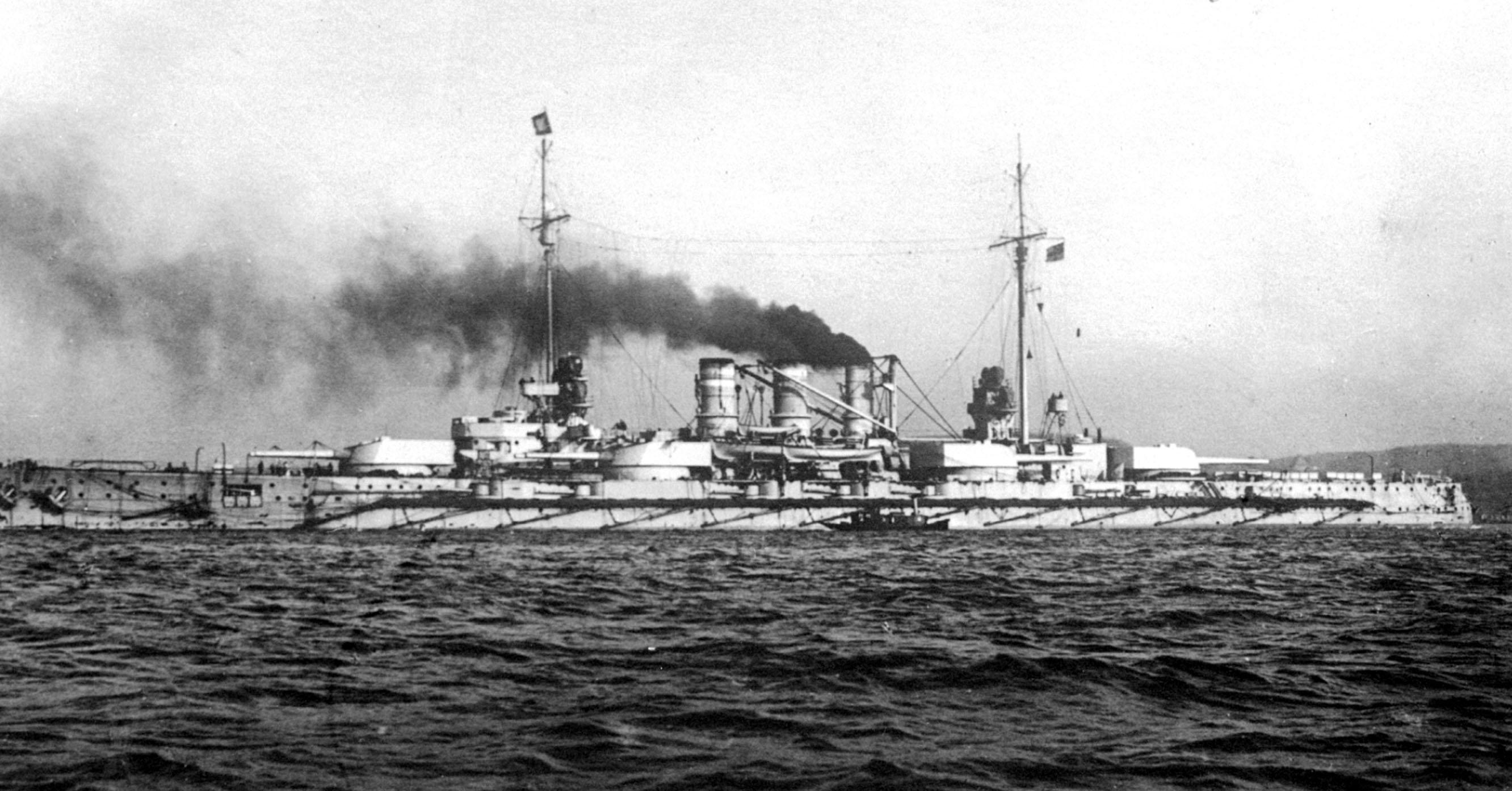

The Battle of Jutland was about to begin, and HMS Queen Mary was soon to be in the thick of it.

Within half an hour she would be blown apart by German shells, and take 1266 officers and men to the bottom of the North Sea. Archibald Dickson was one of them.

Tragically his big brother Robert was present during the battle, on the dreadnought HMS Benbow, though he had no idea at that stage of the fate that had befallen his beloved brother.

In a letter he wrote to his mother, Kathleen, immediately after the battle, he said: “I am awfully anxious about Archie, but we know nothing definite at present. It was indeed a fine sight to see the 1st Battle Cruiser Squadron tearing across our bows firing furiously . . . It was a finer show than anything we ever saw in the Dardanelles. Please wire to me at once when you get news of Archie.”

It would be all too soon that Archie’s family, like thousands of others, would receive the word they had been dreading in the form of a telegram delivered on Friday, June 2.

The letter Kathleen wrote to Robert after the devastating news is heartbreaking.

“My dearest and only boy. We can’t tell each other in writing what we are feeling today – my world was divided into three parts, and a third has crumbled away. You will, I hope, be some boy’s father some day, but you can never be his mother, so you can never know what I am feeling now.

“I am telling the simple truth when I say, that all mothers and sons are not what we are to each other. He had needed me so much always, and I was perhaps too proud of the big handsome man my delicate kiddie was growing into.

“Thank God you missed being in the Queen Mary. I know you will always try to fill a double place, and the memory of our time together is a great comfort to me now.

“You seem so near and real to me now!”

Even 100 years on it is hard to read those words without being deeply moved by the utter pain of loss felt by this one mother among countless thousands whose sons died during those dark years of war.

Her “delicate kiddie” was exactly that when he took his first steps into service at sea.

Although he may have seemed tragically young to have died at Jutland, he had in fact been in the Navy for four years by that point.

After attending Edinburgh Academy until the age of 12, he then entered the Royal Naval College on the Isle of Wight as a naval cadet.

After two years he went on to the Royal Naval College Dartmouth, before being commissioned as a midshipman on the Queen Mary at the age of 16.

His 18-year-old brother Robert – known as Bertie – was a seasoned veteran by the time of Jutland, having already served in the Falklands and at Gallipoli.

He’d even had a tragic connection with one of the most famous names of the First World War. On April 23, 1915, two days before the Gallipoli campaign began, he’d waded through the shallows of the Aegean Sea carrying a corpse from a hospital ship to be buried on shore.

The body was that of 27-year-old poet and British naval officer Rupert Brooke, who had died that afternoon from blood poisoning caused by a mosquito bite.

Although Bertie remained in the Navy until 1952, rising through the ranks to become a rear admiral, neither he nor his parents ever spoke about the Great War. The agony of losing young Archie must have clung to them through the years, never leaving them.

Of course, with a staggering 6094 British sailors killed, as well as 2551 from the German Fleet, many others would have felt the same sense of loss.

Whole communities were affected. In just one day the fishermen’s quarter in Wick in Caithness, received a hammer-blow.

No fewer than 11 local men were lost on HMS Invincible and four on the Queen Mary.

All but two were married. They left 13 widows and 33 fatherless children, as well as mothers, fathers, brothers and sisters.

The 6094 were the obvious victims of Jutland, but so many more – including Archie’s brother Bertie and his parents – bore the scars long after the guns fell silent.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe