They represent the worst of slap and tickle seaside humour and were – and remain – morally dubious, sexist and even exploitative.

Or, according to the author of a new book about the Carry On movies, they are empowering and full of strong women.

Caroline Frost studied the films’ representation of women, class and sexuality, concluding that the notoriously bawdy films have become misunderstood and she says some of the scripts from the long-running franchise might even be considered “defiantly feminist”.

She said: “The comedy of the films demanded women, like their male counterparts, were shoehorned into stereotypes – either stupid and beautiful with their underwear liable to fly off, or sexually frustrated harridans.

“But they offered a lot more than that. As early as 1959, in Carry On Teacher, Hattie Jacques said: ‘Mischief is a form of self-expression’. And even in the early days, Carry On Constable in 1960, Hattie’s police officer said: ‘Strange, don’t you think, that the only efficient rookie is a woman?’

“So, yes, there’s always a big caper, but there’s a message there. This idea that women are always seen as sex objects doesn’t bear out once you watch the films in a linear fashion.

“Carry On Cabby was a defiantly feminist script, recognising that women were no longer prepared to stay at home and cook their husbands’ dinners. Writer Talbot Rothwell had Hattie’s girls using their wiles to steal taxi rank customers away, as well as their brains. Women could be smart as well as alluring and the Carry On team recognised this.”

The author of Carry On Regardless argues that in an industry known for its questionable treatment of women in terms of pay and sexual exploitation, the Carry On girls were given status as equals.

She said: “The female stars I spoke to were all thrilled by their involvement in the films and their legacy. Exploited? Never, they said. Valerie Leon, who appeared in six films as well as being a Bond girl, told me she was treated very well by all involved, while Sally Geeson called it ‘an atmosphere of total respect and equality’.”

Frost writes in her book: “Hattie Jacques, Barbara Windsor, June Whitfield and Joan Sims were all fine actresses who took pride in creating the characters, and what a range it was – from young, romance-hungry, chaste and unchaste girls to older women full of sport and smiles, Lady Ruff-Diamond happy to betray the Empire for a turn with the Khasi, Matron protecting her nurses from Doctor Prodd, Augusta Prodworthy asking quite reasonably, ‘Why isn’t there a female public toilet?’ and Nurse Sandra May admiring that lovely-looking pear.”

Recalling that moment from Carry On Doctor which became one of the most famous lines of the films, and Barbara Windsor’s career, the author said: “This wasn’t Barbara being objectified, it was her getting in on the joke and winning it every time. She giggled conspiratorially with her male admirers, but that was as far as it went with them. In Carry On Again Doctor she made it very clear she wanted to be a woman working in her own right, rather than just the wife of a doctor. She was already stamping out her own territory.

“There she was in Carry On Girls, revving out of town on her motorbike when she realised the beauty competition might be fixed,” said Frost.

“Some people think these films are an exercise in objectification because they picture Windsor being manhandled or objectified by her male voyeurs. But it doesn’t stand up on closer scrutiny. She was smart, and that smartness came out right from the early days, she was always having the last laugh. She let them giggle, but kept her agency intact.

“The idea that there’s any predatory threat is stamped out and undermined – the women are in control, they have choice all the way through and nothing happens.”

And the fact that the women were given equal billing in a male-dominated industry is also a significant part of their legacy, Frost feels. “These women had a chance to express themselves in a way they perhaps wouldn’t have done in other roles,” she said.

“People are quick to say they’re being objectified in Carry On films, but if you compare them to other films at that time, these parts had more lines than they might have got elsewhere. They were very much a part of the troupe, equal and opposite.”

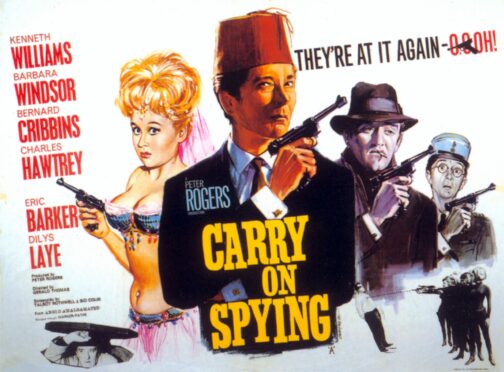

A total of 31 Carry On films were made between 1958 and 1992, forever connecting names like Sid James, and Bernard Cribbins to the franchise, which became a British movie institution.

She was commissioned to write the book prior to 2020’s lockdown, but once Covid struck, she discovered another unexpected quality to the movies. She said: “I had this bizarre experience of the world being frightening and chaotic outside and I’d tuck myself away and disappear into a nostalgic, comedy-fest of the ‘50s-‘70s.

“All you would hear from my house was Sid James’ laugh. That and Kenneth Williams’ ‘Ooh’s’ and Charles Hawtrey’s ‘I say’ got me through lockdown.”

Streaming service Britbox flagged the films for “mild language with mild sexual references, nude images and innuendo” featuring “sexual references, racial imagery and stereotypes that may cause offence”.

Frost agrees that some of the films’ depiction of race were “ignorant” and says some later films in the franchise, such as Carry on England and Carry On Emmanuel were “embarrassing and avoidable”.

But she said: “ When you see people like Bernard Bresslaw playing Charles Hawtrey’s native American son in Carry On Cowboy, then they’re overlooking the inappropriateness of that. It wouldn’t happen now. They didn’t set out to do any harm, they were ignorant as anyone else.”

She added: “Comedy is different these days. We’re free to say whatever we like about all sorts of activities and parts of the bodies, but equally not free because of being scared at who that might offend. In one sense there are no barriers, and too many barriers on the other. The success of the Carry On films depended on innuendo and double entendre and everyone was conspiring beautifully in that.”

Frost also argues that gay actors such as Hawtrey and Williams played important roles beyond the blue humour.

She said: “They were there and they were unashamed. Off screen they had more complicated, challenging lives. But when I spoke to some other older actors one of them said that when you’re growing up in west Wales, to turn on your screen and see people like Williams and Hawtrey being able to express themselves was important.”

Far from being a depressing reminder of the kind of humour many would rather forget, her research found the films offered a refreshing chance to be seen from a contemporary perspective.

She said: “They got me through lockdown in a way I was not expecting. I have a sophisticated cultural palette, but I think they celebrate something special about the consolation of company and comradeship in times of chaos.”

Carry On Regardless, published by White Owl, is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © ITV/Shutterstock

© ITV/Shutterstock