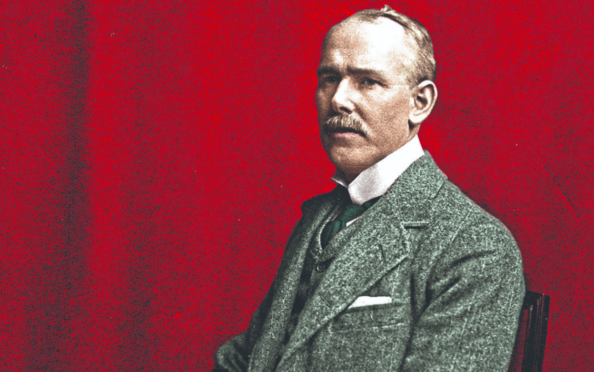

He was one of the world’s most renowned collectors who donated more than 6,000 artworks to his home town, a collection described by Sir Hector Hetherington, principal of Glasgow University, as “one of the greatest gifts ever made to any city in the world”.

However, Sir William Burrell, the shipping magnate who amassed that collection and then gave it away, remains both one of the best-known names and least-known characters in Scottish philanthropy.

Isobel MacDonald, co-author of a new biography, William Burrell: A Collector’s Life, said: “There’s a myth that he came from a very humble background but it was quite middle-class and his family’s home in Devonshire Gardens was full of art. His mother Isabella collected tapestries and textiles, and she was a major influence.

“There was a 1976 BBC documentary about Burrell, The Millionaire Magpie, that gave people the impression that he collected objects randomly and that he counted his pennies but we had access to archived letters from William Wells, who was appointed keeper of the collection in 1956, and he said Burrell would have been embarrassed if he had been asked about an object and couldn’t talk about it knowledgeably.”

The Millionaire Magpie

Burrell, who was born in 1861, left school at 13 to join his father and brother in the family business as a shipping merchant. He bought his first painting while still at school, with a few shillings he got from selling a cricket bat. It was the beginning of his 75-year collecting career.

“William Burrell’s art collecting first found its expression with work by the Glasgow-based animal painter George Brown, known familiarly as ‘Coo Broon’. The story goes that his father was less than impressed with his interest in art, suggesting that he would be better off investing in a cricket bat,” said MacDonald.

“He didn’t have a traditional education, but when you look at the heavy annotations in the books in his library, it’s clear he was trying to teach himself. Far from being a random and wide selection of artworks, his collection was considered, showing a real interest in artistry and craftsmanship, which you can see through his early support of the architect Robert Lorimer, who was connected to the Scottish Arts and Crafts movement.”

The authors had access to Burrell’s correspondence with Lorimer, held in the archives at the University of Edinburgh, which showed a different side to the wealthy businessman, who came to be known as a difficult man, driving a hard bargain with art dealers and the museum directors to whom he loaned parts of his collection.

“He would change his mind and could be difficult, but a lot of that was in his later life,” said MacDonald. “His early letters show how passionate and excited he was about finding objects as a young man, detailing trips to Vienna where he scoured the antique dealerships and was beginning to learn about ‘the game’, as he called it.”

There’s no doubt that Burrell was a hard-headed businessman who amassed a fortune by selling his fleet during boom times and buying up steamers during depressions. He was a canny collector who built a large, impressive collection, but not at any price, setting himself limits and refusing to pay more than what he thought something was worth.

“He approached his art purchases as business transactions,” said MacDonald. “He let his heart select the objects, but it was his head that bought them. Although he tried to get things as cheaply as possible, he always insisted that the dealers received a fair commission and he was meticulously punctual when it came to settling his bills.”

Burrell is sometimes compared to collectors such as the American newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst but, according to MacDonald, “he was rather disdainful of Hearst saying that he ‘paid whatever was asked whether genuine or spurious’. Later, Burrell was able to buy parts of that collection for a fraction of what Hearst paid.”

The biography comes out next month to coincide with the reopening of The Burrell Collection after a £66 million refurbishment with a third more gallery space to show more of the unique objects, some of which have not been seen for decades. Previously only 10% of the 9,000-strong collection, which has been added to over the years, could be displayed. The collection has important late-Gothic and early-Renaissance European art, including tapestries, stained glass and furniture that once graced Hutton Castle, near Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Burrell, who supported the construction of Glasgow School of Art designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh and was knighted in 1927 for services to art, spent his later years with his wife, Lady Constance, and their daughter, Marion, at the castle. The Burrell Collection includes the finest collections of Chinese porcelain in the UK, as well as 19th Century French art, with more than 20 works by Edgar Degas, paintings by Manet, Cezanne, and sculptures by Auguste Rodin.

He knew what he wanted and always knew how to get it

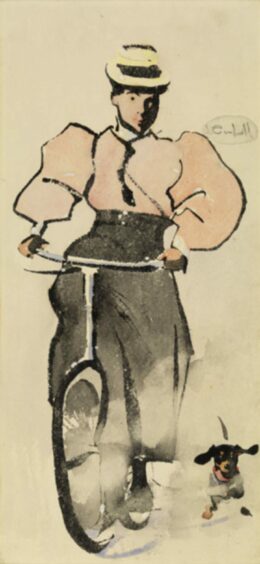

Sir William was a judicious collector, one of the first to buy Degas and Rodin when they were considered avant-garde and scandalous. There are also paintings by Whistler and Rembrandt, and by Glasgow Boys John Lavery, James Guthrie and Joseph Crawhall. The collection includes 140 works by Crawhall which Burrell bought despite the artist being denigrated by critics at the time.

“Burrell proved to have an innate talent for art collecting,” added MacDonald. “He understood what he was buying, and his refined taste led him to areas that other collectors dared not touch.” Burrell was fascinated with objects that had a royal connection, including a valance that adorned the marriage bed of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, believed to have been embroidered by the young queen herself. Other royal artefacts include a bedhead from the marriage of Henry VIII to Anne of Cleves, a hawking set owned by King James IV and I, and Prince Charles Edward Stuart’s christening apron.

Burrell believed in free education for all and wanted the nation to be able to share his delight in his collection, donating it to Glasgow in 1944. At the time of his gift, the collection was valued at more than £1 million and it came with £450,000 in cash to build a dedicated museum for it, but one that had to be well away from the city and pollution to protect the fragile tapestries.

After more than 30 years of searching for a suitable site, Glasgow obtained more funds from the Government and commissioned a purpose-built museum in Pollok Country Park, which was opened by the Queen in 1983 and has been compared to the National Gallery and the V&A in London.

“The opening occurred at just the right time to play a major role in the transformation of Glasgow from a post-industrial city with a poor reputation into an internationally renowned city of culture,” said MacDonald.

“I’m looking forward to The Burrell Collection re-opening. Every object was chosen by Burrell for a reason. There’s a reflection of him in each one and a story behind it.

“There is no doubt that Sir William was a difficult and complex character. He was immensely proud of his achievements but unwilling to brag about them.

“His actions in business and art were bold and daring but in person he was softly spoken and shy. He was socially and politically conservative but had an adventurous taste in modern art. And, like all men who reached his position, he had a ruthless streak. He knew what he wanted, and he knew how to get it.”

This excerpt from William Burrell: A Collector’s Life examines how he went about his business and collecting.

There is no doubt that Sir William was a difficult and complex character. In many ways he was a typical west of Scotland male; he was immensely proud of his achievements but unwilling to brag about them. His actions in business and art were bold and daring, but in person he was softly spoken and shy. He was socially and politically conservative, but had an adventurous taste in modern art. And like all men who reached his position, he had a ruthless streak.

He had exacting standards and expected others to meet them. This manifested itself in business when his younger brother was ousted from the family firm for not quite making the grade. In his personal life, when his daughter Marion made inappropriate romantic liaisons, he quickly intervened to call off her engagements.

In dealings with museums and galleries he was extremely demanding, though always scrupulously polite. He frequently began his letters with “Sorry to trouble you”, or “I hope I am not imposing upon your kindness”. After a particularly protracted and demanding correspondence with the director of the Tate Gallery he wrote: “I know I am making myself a nuisance but I seem to be asking you one favour after another.” He knew what he wanted and he knew how to get it.

Burrell was very much a product of the British Empire. His view of the world was based on growing up in Victorian Britain where it was considered part of the natural order of things that Britain controlled an empire and used it to advantage.

His business as a shipowner was founded on Britain’s dominance of maritime trade, at a time when nearly half the world’s ships were British, and much of this trade was a result of the exploitation of people and resources across the empire. His view of different peoples and cultures was seen through the eyes of a Victorian industrialist art collector. For example, he revered the bronze and ceramic art from China in his collection but exploited ordinary Chinese seamen on board his ships.

As with most collectors of this time, Burrell acquired a small number of objects that are today regarded as war loot or the plunder of empire. In a few cases he knew exactly how these pieces had been acquired but, with the sensibilities of the time, this was not considered problematic, just a natural consequence of British rule. But in most cases he was completely unaware, and it is only with modern research techniques and the opening up of digital archives and collections that the true provenance of some parts of the collection has been revealed.

It would be harsh to judge Burrell on this basis as in fact he was largely ethical in his approach to collecting.

William Burrell: A Collector’s Life by Martin Bellamy and Isobel MacDonald will be published by Birlinn on March 3

Collection’s stunning home reopens after £68m refurb

By Ross Crae

History lovers will soon be able to enjoy Sir William Burrell’s spectacular collection again as the museum dedicated to it reopens after a £68 million refurbishment.

The A-listed Burrell Collection will open next month for the first time since 2016 with capacity increasing by more than a third.

A new entrance and central stairway have been created to help people explore all three floors of the building for the first time. The outdoor green space has also been transformed and linked to its surroundings in Pollok Country Park.

A 35% expansion in gallery space will allow for more objects from the collection to be put on show, some for the first time. New displays will give visitors a better understanding of the artworks, the people who made them and some of the people who have owned them.

When the attraction was closed, the decision was made to lend and loan exhibits to museums and galleries around the world.

Pre-lockdown, the Burrell On Tour initiative meant treasures were seen by more than a million people, from New York to Amsterdam and London to Melbourne. The decision to take the works on tour was controversial, with Burrell’s bequest dictating they were not to be lent outside the UK.

However, a change in legislation paved the way for the loans which have been positively received.

Duncan Dornan, Glasgow Life’s head of museums, said: “It was a great chance to deploy the collection in a different way.

“We’ve been able to put Burrell’s works up against some of the finest holdings internationally. It really identifies it as a key international collection and helps put Glasgow very firmly on the map.”

Staff working on the refurbishment also had some fun during lockdown in 2020 by recreating some of the works and posting them on social media.

Using only objects found in their homes, they created replicas of some of the collection’s most famous works in a bid to keep people connected with the city’s treasures.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums

© CSG CIC Glasgow Museums