SHE was a key witness in the Glasgow murder case that was to rock high society and fascinate the creator of the world’s most famous detective.

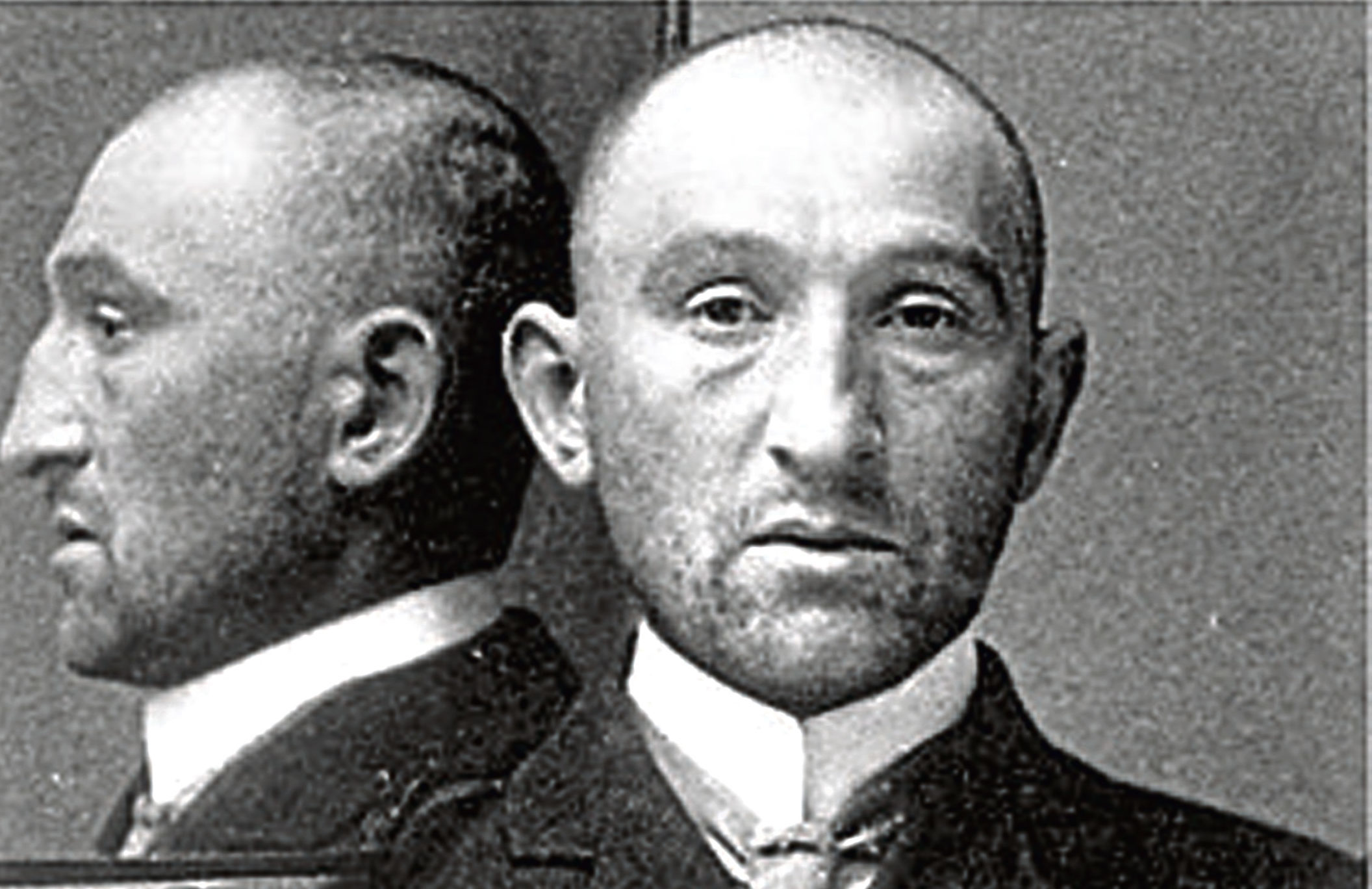

In December 1908, handmaid Helen Lambie stepped out to the shops, leaving her mistress alone for 10 minutes. By the time she returned, her employer, wealthy spinster Marion Gilchrist, had been bludgeoned to death. Lambie went on to become the central witness in the conviction of petty criminal Oscar Slater, who was sentenced to death.

Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle became fascinated with the murder and he turned his detective skills to clearing Slater’s name. Now, 110 years later, a New York Times journalist’s investigation has raised fresh questions over the handmaid’s tale.

Margalit Fox’s book Conan Doyle For The Defence points to 21-year-old Lambie as being vital to cracking the case. Speaking from New York, where she writes obituaries for her renowned newspaper, Margalit said: “Helen was described as cunning, crafty and being out for herself. What is astonishing is her employer was murdered during the 10 minutes it took to buy Miss Gilchrist her evening paper.

“What’s also notable is when she comes back to the flat with the downstairs neighbour who heard the crashing noises from upstairs is what Helen does, or doesn’t do. She doesn’t go looking for her mistress right away.

“And Helen sees a well-dressed stranger brushing past them and tearing down the stairs yet doesn’t say anything. If you were returning home and saw a strange person leaving your home you would say ‘stop, who are you?’”

Margalit explains how Arthur Conan Doyle called this “negative evidence”. His creation, Sherlock Holmes, used negative evidence in The Adventure Of Silver Blaze published nearly 20 years earlier, where a dog failing to bark ruled out the presence of a stranger at a crime scene.

“From then on Lambie was very secretive and unforthcoming in terms of talking about the case,” she said. “In 1927 she released a newspaper statement recanting her testimony, but a short time later she recanted her recantation.

“Lambie was living in Illinois here in the USA. One thing I uncovered were astonishing letters from Lambie to her mother. They’re in this childish scrawl, but they urge her mother to continue to not talk to the press. Over time, you can see from her letters that Helen seemed to get more and more invested in persuading herself of Slater’s guilt.”

Margalit maintains she is undecided about the truth of who murdered Marion Gilchrist – and that Helen, who died in 1960, took her secrets to the grave…and that includes the real identity of the killer.

“If I had to ask her one question it would be who she saw that night,” she added. “The evidence suggests she recognised the man who left the flat. Helen told Miss Gilchrist’s niece that she saw the man, and it was a highly placed member of Glasgow society.”

One of the theories is that Helen identified a physician who knew the victim. Subsequently, though, the murder was blamed on immigrant Slater, in what was described as a robbery gone wrong.

It sounds like a far-fetched conspiracy theory, but in 1914 a Glasgow detective, John Trench, released a document showing how his colleagues had doctored evidence. They suppressed the name of the doctor from the witness statements.

Slater had been convicted, though, and was sentenced to hang – which at the time could not be appealed.

Margalit said: “The truly terrifying thing was he was sentenced to death, and that was it. Scotland did not have a process to appeal such a sentence. There were very rare cases were sentences were reversed, but it had to be done by the monarch. That’s what happened when Slater’s conviction was commuted.

“But when the judge donned the black hat (a three-cornered tricorne which judges wore when passing a death sentence) it had a terrible finality.

“In part thanks to the agitation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Slater’s other supporters there is now a Court of Appeal in Scotland.”

It took nearly 20 years for Slater’s conviction to be quashed, though.

And, despite seeming like his foray into becoming a real-life detective was a success, the affair ended on a sour note for Conan Doyle, who had invested considerable time and money in clearing Slater’s name.

“In the end, Slater got £6,000 compensation which was quite a lot of money. He was a threadbare immigrant and he wasn’t prepared to reimburse anyone for any expenses. Conan Doyle was a Victorian man of honour, and insisted Slater reimburse people – including himself.

“Sir Arthur was very rich, this was about principle and honour. He and Slater had a vitriolic exchange of letters, first between themselves and then played out in open letters and articles in newspapers.

“The most shocking and painful thing I found in my research was a headline ‘Conan Doyle v Slater’ – eventually he had to take Slater, the man he had fought to free, to court.”

The case kept Conan Doyle captivated for decades, and Margalit can relate.

For three decades she pondered the murder of the Glasgow spinster after first reading about it on the New York subway.

“I was in my twenties and working in an uninspiring job in publishing,” she said. “It was on the subway one day when I was reading a biography of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle from 1949.

“Towards the end of the book, almost as an aside, there was a casual mention of how Conan Doyle investigated the wrongful murder conviction of an immigrant man, Oscar Slater.

“I was stunned, the creator of the foremost literary detective in the world played detective in a murder case? Why isn’t this better known? I hadn’t gone to journalism school so I put it in the recesses of my brain where it stayed for 30 years.”

As part of her investigations, Margalit visited Scotland twice, visiting the National Archives in Edinburgh, Glasgow’s Mitchell Library, and Peterhead Prison, where Slater was held for 19 years.

“I came back to Scotland last year,” she added. “I took a trip to Peterhead. The prison was once the most notorious in the UK and is now a museum.

“It was fascinating and I got to stand in the cell Oscar Slater occupied for nearly 19 years.

“In terms of atmosphere that gave me something you can’t get from visiting libraries and archives in Edinburgh or Glasgow.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe