HE had the legs for a kilt, enjoyed a pint, and had a fierce wee dog, if crime-fighting reporter Tintin didn’t have a Scots granny, he should have had.

The cartoon sleuth celebrated his 90th birthday on Thursday after taking on his first mission in the pages of Le Petit Vingtième, the children’s supplement of a Belgian newspaper, in January 1929.

But experts said it was not until he took a trip to Scotland eight years later that Tintin stopped being… well, a little bit racist.

Tintin and The Black Island was published in 1937, and, according to Professor Laurence Grove, that would signal both a stylistic and ideological change for the famous Belgian.

Read today, earlier adventures could be seen as racist and anti-Semitic but Scotland was the first place where Tintin creator Hergé, born Georges Prosper Remi, gave his leading man more understanding and cultural awareness.

Professor Grove said: “That book for me is the one that’s key to the whole series.

“It marked a change in terms of Tintin accepting other people, him becoming like other people. He goes from looking at other cultures from the outside to taking on other cultures.”

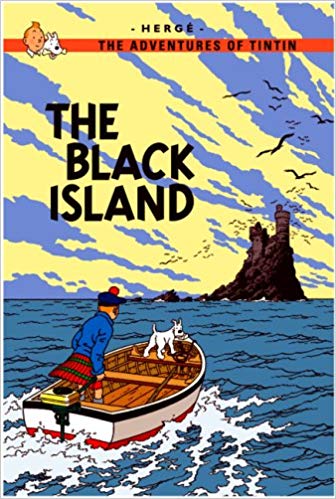

Inspired by The Thirty-Nine Steps, The Black Island sees the cunning reporter follow a criminal trail through England before heading north.

Tintin and his faithful companion Snowy head out to sea to an island castle to confront the masterminds behind a forgery plant.

Grove, a professor of French and Text and Images at the University of Glasgow and leading Tintinologist, points to the scene where Tintin dons a kilt as a key indicator of the series’ turning point.

“He’s not saying ‘I’m going to tell you what to do’, like previous adventures in the Congo or America,” he says. “This is Tintin saying ‘I’m going to be like you and by doing that I’m going to help solve the problem’.

“It’s why I think Tintin could be great for Brexit, if we had a bit more Tintin around us we might get things done a lot more happily. He’s probably the perfect person for it – he’s got his own national identity but he’s part of a togetherness.”

Grove says the story, which in recent years has been translated into Scots as The Derk Isle, also marks a change in the illustrative style of Hergé.

First released in Le Petit Vingtième between April 15, 1937 and June 16, 1938, it was put together in a book in 1943.

Publishers then pointed out 131 errors in that would have to be altered before the English language version went on sale in the sixties, which were put right thanks to research in the UK by Hergé’s collaborator Bob De Moor.

Grove says: “Stylistically, it was the only one that was updated twice and the final version done for the English language translation is almost the epitome of the clear line style which influenced Andy Warhol and Roy Liechtenstein.

“The Black Island is the key story stylistically and also ideologically.”

Tintin’s enduring appeal means that, 90 years on, his adventures have been read by millions worldwide and continue to be popular.

“When you grow up with it, it changes your outlook on the world,” says Grove, who read the books alongside tales of Asterix and Obelix while growing up as part of a family originally from France.

“Tintin is James Bond without the girls, the base of all modern fiction. He is the one we can all recognise. We can all have an everyday life as Tintin does as a boy scout or hanging around his flat, taking his dog for walks.

“Then something happens which destabilises the situation and he goes off on an adventure. He solves the problem then goes back to being normal again. For me it’s exactly the same thing as most modern fiction, he allows us to recognise ourselves in him but also who we want to be.”

Searching for the real Black Island

Like many other Tintin adventures, The Black Island helped open up new worlds to people.

Before he rocketed to the moon and searched the Caribbean for pirate treasure, this story saw him explore a place that was close to his European home, but still a little distinct.

“There’s a huge pull for French speakers to Scotland in terms of tourism,” Grove says. “It is recognisable but completely different – one of the last wildernesses in Europe.

“You’ve got scenery, the like of which you couldn’t dream of anywhere else, as well as particular customs – Highland Games, kilts, whisky – which are very distinct to Scotland.

“But at the same time, it’s European and recognisable and tourists who come here generally don’t feel threatened. It’s being in a different world without being threatened.”

In 2017, Grove assisted a French TV crew in their own search for the famous Black Island, and the iconic castle perched atop.

They had a modern day Tintin – a travel blogger named Alex – who went on a hunt for the location using just the image of the front cover.

After visiting the Black Isle, near Inverness, and Ben More on the Isle of Mull amongst other red herrings, they eventually headed to Lochranza on the Isle of Arran, where De Moor had sketched the castle on his fact-finding mission to the UK.

Alex borrowed a boat to recreate the iconic image as best as they could.

“On the way it was about discovering Scotland, discovering differences,” Grove says. “The final conclusion was if you look at the castle, some of it is from Lochranza Castle and some of it is from Hergé’s imagination.

“The idea is that life is a bit like that, based on fact but also what we make of it.”

The Scots inspirations for the story also include the lead villain, Dr Müller, who is thought to based on Dr Georg Bell, a Scot who moved to Germany and took on the nationality.

He was linked to the Nazis and was involved in counterfeiting money.

There are also rumours of a monster on the Black Island, based around the myth of Loch Ness which had just started to be popular at the time.

The monster actually turns out to be a trained gorilla, closer to King Kong – a blockbuster hit around the time of publication.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe