The darlings of the pandemic have been feeling the pinch. Peloton’s home-fitness equipment sales are in a spin, Just Eat’s profit margins are on a diet, and now TV streamer Netflix has announced inflation, the war in Ukraine and fierce competition contributed to a loss of subscribers for the first time in more than a decade and predicted deeper losses ahead, marking a sudden swing in fortune for an entertainment company that thrived during the pandemic.

The streaming giant recorded a 200,000 drop in subscriptions this year, a figure that could increase to two million by the end of this summer as the cost of living crunch closes in on entertainment. As well as households cancelling, Netflix also faces intense competition from rival streamers such as Amazon Prime and Disney+ in a saturated market. Suspending its service in Russia after the Ukraine invasion has also taken a toll, losing them 700,000 members.

In another sign of unease, billionaire investor Bill Ackman, who bought £850 million in shares in January declaring he was “all-in on streaming”, has just dumped the lot, swallowing a £300m loss in his haste to get all-out of his Netflix investment.

With 220m subscribers globally, Netflix remains the market leader; yet last week’s figures are a concern for entertainment on demand, signalling that growth has stalled, for now at least.

It was all so different two years ago, when the pandemic and enforced isolation created the perfect conditions to boost streaming platforms. We were an audience stuck at home with plenty of time on our hands. Netflix’s documentary series Tiger King produced the streamer’s first watercooler moments, at a time when few of us went anywhere near an office watercooler.

Is an audience switch-off bad news for us couch potatoes? It is if you like choice. Big film studios cling to franchises and reboots. It’s been streaming services who have funded smaller original productions such as comedies, art house shows, psychological thrillers and edgy indie material. This year producers of the award-winning The Power Of The Dog have been frank about their struggle to find funds from the big motion picture studios. Without Netflix, it would not have been made.

Even if you don’t have a Netflix subscription, streaming platforms are important to the Scottish economy, especially its film and TV industry. Last year Netflix shot its cosy Brooke Shields romcom A Castle For Christmas across Scotland, while Amazon’s supernatural thriller The Rig, starring Mark Bonnar and Martin Compston, was the first Prime Video series to shoot exclusively here. Edinburgh’s FirstStage Studios, run by actor-director Jason Connery and his business partner Bob Last, has also hosted two Neil Gaiman series: the eagerly anticipated second season of David Tennant’s Good Omens, and the fantasy show, Anansi Boys, starring Whoopi Goldberg, while Glasgow spent this winter doubling for Gotham for HBO Max’s Batgirl.

Netflix’s current woes also raise interesting questions for Nadine Dorries’ plans to privatise Channel 4. The UK Culture Secretary claims C4 would benefit if it resembled a streaming service. The public may look at Netflix’s huge debts and subscription nosedive and wonder why on earth the Government is launching Channel 4 into a privatised broadcasting sector just when that market is stagnating. The biggest problem for Netflix is that it has spent lavishly on film and TV content, is already £12 billion in debt, and lacks the deep pockets that Apple, Amazon or Disney have, making it vulnerable to a margin squeeze.

Already it is increasing its subscription prices by 17%, another price hike for households. It also plans to crack down on subscribers sharing their password with family and friends, estimating that more than 100 million non-paying households enjoy the service in this way. A trial scheme in South America charged customers an extra sum if they shared their account with another household – although recent data suggests UK viewers are pretty well-behaved in this respect, especially compared to the rest of Europe.

Another tactic may be introducing advertising, perhaps as a second cheaper tier for subscribers, although this would be a major shift in company policy. “No advertising coming on to Netflix, period,” co-CEO Reed Hastings has said, repeatedly, over several years – until last month its chief financial officer signalled a change of heart. “Never say never,” quipped Spencer Neumann. “It’s not like we have a religion against advertising.” Commercials breaking up Bridgerton might be a turn-off for some viewers, but many advertisers will be switched on by the prospect.

Other strategic shifts could include following Amazon and Apple and buying up exclusive sports rights, making live events the next competitive battlefield. Ramping up merchandise is another possibility – already Netflix sell Squid Game tracksuits and, quaintly, Stranger Things cassette decks. Adding gaming to the Netflix menu may win over Generation Z, those consumers aged 14 to 25 who spend more time playing games than watching movies or TV series at home, and already the company has snapped up a trio of small gaming studios

However, the most seismic change could shake the sofa of every couch potato. In the last decade streaming has changed what we watch and how we do so. This year Netflix may opt to dismantle one of its defining features: binge-watching. When House Of Cards debuted in 2013, it was the first big-budget TV series that allowed viewers to watch the entire season’s 13 episodes at once. Of course, this was not the birth of binge, as anyone with access to DVD or video box-sets will recall – but the Kevin Spacey political drama was the first time that a new show was made available ahead of a TV schedule on a single day, leaving pacing to the viewers.

Since then, subscribers have been able to spend hours working their way through shows such as Stranger Things or The Crown. We’re the first generation who don’t have to wait a week for the next episode but showrunners don’t like bingeing: it prioritises plot over character, tone or texture and instead of discussing and dissecting episodes for a whole six days after each episode, a year of work can be inhaled in a few hours.

“Never before in the history of the English language has ‘binge’ been associated with something healthy or productive,” joked Damon Lindelof, whose shows include ambitious TV sagas like Lost and The Leftovers. It’s certainly a far cry from the suspenseful storytelling tradition of Charles Dickens, who was advised by Wilkie Collins: “Make ‘em cry, make ‘em laugh, make ‘em wait.” Research suggests that binged shows generate an initial intense spike of interest, then fade from public conversation. Last year’s Stranger Things netted 8.2 million Twitter mentions its first week of release. By week five, this had dwindled to 800,000.

Crucially, bingeing also shortens subscriptions. Research firm Antenna found many customers signed up for a major movie or series then unsubscribe a short while later. Some have already returned to the old ways. Last year Disney+ turned their Star Wars spin-off, The Mandalorian, into a weekly event. Delighted with the result, they have now done the same for their Marvel audience with WandaVision, Loki and Hawkeye.

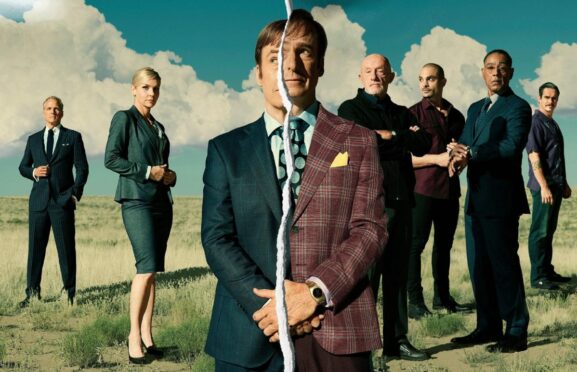

Already there are signs Netflix is modifying its scheduling. When the hit crime thriller Ozark began its fourth and final season in January, many fans were surprised that only half of the 14 episodes produced were made available. They have been asked to wait – and presumably maintain their subscriptions – months for the concluding seven shows. Last week’s big release, the final series of Better Call Saul? One a week.

Will this new approach be enough to turn Netflix’s fortunes around? Unlike bingewatchers, we’ll have to wait and see.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe