From spooky castles and American high schools to swinging London and the Wild West, vampires have for generations been out for blood any time, any place, anywhere.

However, according to popular culture historian Sir Christopher Frayling, there is a common thread running through the undead’s regular reincarnations on the big screen. And it’s not garlic and silver bullets.

He says the ability of vampire movies and the Dracula myth to tap into contemporary anxieties is the secret of their enduring success.

“Some myths cease to work, like Westerns, based on a huge American myth that ran out of steam,” he says. “But the vampire is a shapeshifter that can transform with the times and express the changing anxieties on people’s minds.

“One function of horror movies is to say what is very difficult to state in the mainstream form. Take a sideways step into fantasy and horror and it becomes possible to say the unspeakable. You can be more transgressive and radical.

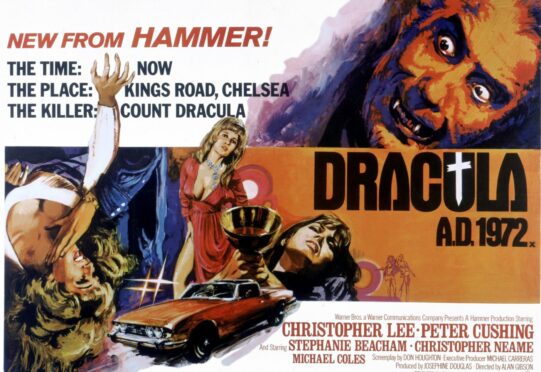

“In literature, Bram Stoker was dealing with all sorts of things that buttoned-up Victorian society was incapable of talking about but he got away with it because it was in the form of horror. In British film – up until the Hammer explosion of colour, bosoms and vampires in the late 1950s – everything was butlers, people speaking the Queen’s English and being repressed. There was a huge sigh of relief that somebody knew how to say something else, even if it was in a horror setting.”

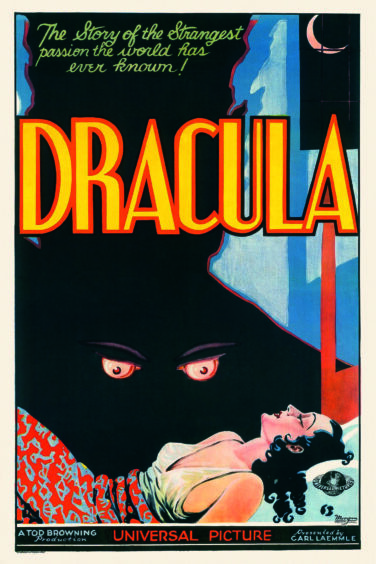

Before Hammer, though, was the first vampire film, Nosferatu, which was released in 1922. It prompted Frayling’s new book, Vampire Cinema: The First One Hundred Years, a cavalcade of colourful posters and eye-catching images of some of the genre’s most important films and television shows.

“I heard a lot of people talking about this year being the centenary of James Joyce’s Ulysses and TS Eliot’s The Waste Land but it is also 100 years since Nosferatu was released. Instead of just talking about highbrow culture, I wanted to draw attention to the origins of horror cinema and certainly vampire cinema,” adds Frayling.

The German-made film was heavily inspired by Stoker’s Dracula but the names were changed to avoid copyright issues. It was a haunting film, almost arthouse in approach, and it portrayed the vampire not as a seductive, cloak-wearing count but as a hideous and rodent-like predator.

“In Nosferatu, they introduced the idea of the vampire as a bringer of plague,” adds Frayling. “When the death ship sails into Bremen, with it comes the rats and, before you know it, a pandemic. Audiences who saw the film had just gone through the pandemic of the Spanish flu which killed more people than the First World War, so a film about a pandemic would have hit audiences very hard.

“Thinking about what we have just been through over the past couple of years, my guess is we will get vampire films about the pandemic next year. We can carry anxieties and thoughts via the vampire movie and I suspect this will be the next thing.”

Frayling’s introduction to the world of vampires was the 1958 version of Dracula, where Christopher Lee played the title character for the first time and Peter Cushing was his nemesis, Van Helsing.

The 75-year-old recalls: “I set off on my bicycle to see it and I was supposed to be back at boarding school by the evening but the lure of Van Helsing pulling back the curtains and turning the Count to dust was too much and I ended up getting back to school late.

“The movie was in colour, it was set in Victorian times rather than the present day, and there was a sexual element. All three were heady thoughts for an adolescent boy. I was much too young when I saw these early Hammer films and they made an impression.

“I turned to the literature after, whereas a lot of people read the gothic fiction first and then see the films. I was intrigued, partly because of the tingle of fear but also because I couldn’t understand why people didn’t take it more seriously. Everyone was studying realism – DH Lawrence, Dickens – but what of the fantasy works, of fairytales and horror stories that were metaphors for life? It became a crusade for me to have this taken more seriously.

“I wrote a book about literary vampires, from Lord Byron to Bram, years ago. When I was in the old reading room of the British Library in the ’60s, examining horror literature, the people bringing the books to me would place them down as if they were tainted or infectious and look at me as if to say, ‘Do you really want to read this?’

“Now it has turned around and everyone loves gothic fiction, horror and fantasy, and few are interested in realism. Maybe that’s because the real world is so scary and so you take a sideways step. Everyone in the new British Library is reading gothic literature. Realism is out at the moment. We don’t like confronting things directly; we like telling fairytales.

“I no longer have to lower my voice and feel that it is a guilty pleasure because I enjoy horror. Now it’s conventional.”

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde: 135 years on, why literature’s famous alter ego remains at large

Sir Christopher points to the ’70s as a time when vampires stepped out of old castles and period trappings to become an everyman figure.

“The publication of Salem’s Lot by Stephen King got rid of the cloak and evening wear and the British class system, and transported it to small-town America where everyone knew each other. The vampire could sit in everyday life and it enabled hundreds of vampire films to do likewise afterwards.

“Then there was Anne Rice’s Interview With The Vampire, where the vampire becomes a conflicted figure. There is a psychology to it and he is no longer just a bogeyman but he becomes an addict-like figure. He doesn’t want to be a vampire but is condemned to eternal life.

“He goes from being a soulless creature to a lost soul, and suddenly vampires become interesting characters in their own right and can be sympathetic.

“Look at Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula in 1992, where Gary Oldman’s vampire is very romantic and trying to find his lost love, while Anthony Hopkins’ Van Helsing is a crazy fundamentalist wandering around with a cross shouting at people. The whole story is reversed yet it still works as a vampire film. The genre is almost infinitely flexible.”

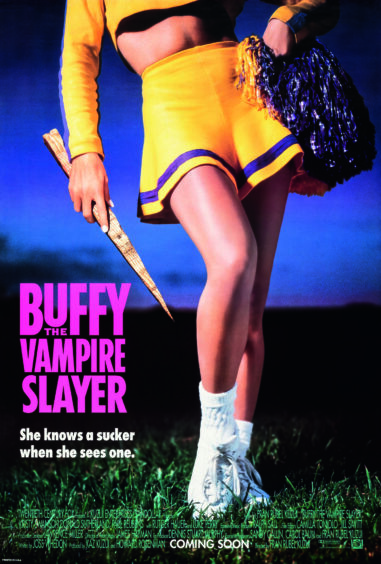

Prior to Coppola’s version, the ’80s repositioned vampire movies for a younger audience, in films such as The Lost Boys and The Hunger, starring David Bowie. Frayling says: “There are two strands to it – the likes of Buffy The Vampire Slayer and the Twilight movies where, in the case of Buffy, it’s an adolescent girl dealing with school, homework and which groups she belongs to, while also fighting a cosmic battle. Then there are superhero vampire movies like Blade, Van Helsing and Morbius. The trick was taking these films away from a mature audience and making them appeal to an adolescent audience. Sex from the neck up is very appealing to adolescents – it’s an uncomplicated thing.”

Choosing which of the hundreds of vampire films to include in the book was difficult but there is no doubt which is the historian’s favourite.

“I’m sure I will receive a lot of comments on Twitter and receive letters,” he laughs. “It was partly based on my favourite films and partly on the strongest images. Sometimes the films are terrible but their posters are great. I wanted the book to adopt art values in a popular subject, so the visual qualities of an art book applied to this. My favourite vampire film is Let The Right One In, which is a Swedish movie. It’s about a little boy, Oskar, who lives in a Stockholm housing estate and is being bullied at school and is quite troubled. This ragged little girl, Eli, moves in next door and she’s a vampire. They develop a close relationship and she helps him find his voice.

“It’s a very beautiful movie and it uses the vampire metaphor in lots of ways. It takes the traditional aspects of the vampire story and reworks them into an adolescent and suburban setting in Stockholm.”

Frayling believes the time is perfect for a celebration of vampires in film.

“There are an extraordinary number of vampire commemorations this year,” he adds. “Not only is it the centenary of Nosferatu but it’s the 125th anniversary of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, 150 years since Carmilla, which is the great lesbian vampire story, 30 years since Coppola’s Dracula and 25 years since Buffy began on TV. It’s incredible that all of these anniversaries come together in 2022. It’s the year of the vampire!”

Delphine? Just fangtastic

Christopher Lee might be the quintessential cinematic vampire, having played the role nine times, but he isn’t Sir Christopher Frayling’s favourite big-screen bloodsucker.

Instead, that honour goes to Delphine Seyrig in 1971’s Daughters Of Darkness.

“She was a French actress and she plays the Countess as a sort of elderly Hollywood star past her prime, a reclusive version of Marlene Dietrich,” he explained. “It’s a brilliant performance and it sticks in my mind very much. She destroys a young couple’s marriage at a seaside hotel. She is reclusive, destructive and beautiful.

“My least favourite is Tom Cruise in Interview With A Vampire. Believing him as a bewigged 18th or 19th-Century vampire is, for me, mission impossible.

“Vampires are great roles for an actor to get their teeth into, if you’ll pardon the pun, because you need to be a little over-the-top, self-assured and charismatic. Claes Bang’s version on TV a couple of years ago was a clever one. That really shook me and having seen so many vampire movies, it takes a lot to shake me.

“If you’re not careful, though, the part can take you over. Bela Lugosi was indelibly associated with the role. Christopher Lee was always keen not to be entirely associated with Dracula as he wanted to be seen as versatile.”

Vampire Cinema: The First One Hundred Years, by Christopher Frayling, is published tomorrow

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe