It was a life-or-death dash across Europe – 1,000 frantic miles from Florence to London.

A hospital doctor as well as a diabetic, RD Lawrence, Robin to his friends, knew the odds better than most and they were not good. While starvation diets could delay the inevitable, in 1923 diabetes meant only one thing – certain death.

His dream was to become a professor of surgery and Lawrence had made a good start, graduating with flying colours from Aberdeen University. He moved south and was a rising star as an assistant ear, nose and throat surgeon at King’s College Hospital in London. He took risks – sneaking into the post-mortem room in the evenings to practice on cadavers. A bone fragment once flew into his eye causing serious infection.

More alarmingly, tests also revealed he had diabetes. Dismayed, he decided not to go home to Aberdeen and be a burden on his mother but to work out his final days as a general practitioner treating the expat community in Florence.

By this time, he was unable to walk up stairs, and numbness in his fingers and feet indicated peripheral neuritis, as a biography by his daughter-in-law, Jane, reveals. Then came a telegram from Geoffrey Harrison, his friend and colleague at King’s: “I’ve got insulin. Come quick. It works.”

Lawrence loaded up his Morris car and enlisted a chauffeur – an Italian mechanic who wanted to visit his son who ran a restaurant in Soho.

It was a gruelling journey. His chauffeur wouldn’t drive in the streets around Paris nor after their arrival in England, leaving Lawrence to take over the wheel, peering ahead with just one good eye. They finally arrived. Dr Harrison gave the first injection on May 31 – guessing the right dose, as he had to. It worked. Two months later, Lawrence was back on his feet and able to control his diabetes through insulin injections.

The speed with which insulin had been discovered and then made available was astonishing. Medicine had known nothing like it.

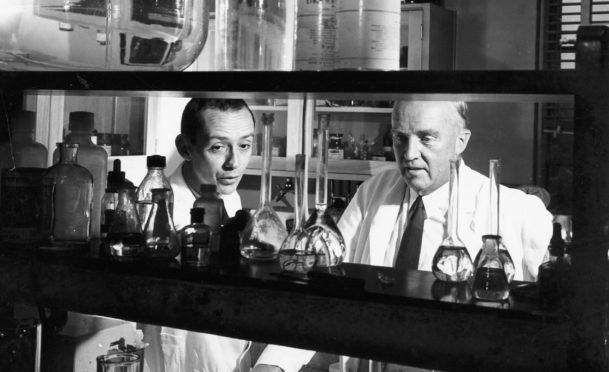

The experiments had started exactly two years earlier by a young Canadian surgeon, Fred Banting, at the University of Toronto under the supervision of Aberdeen-trained professor of physiology John (JJR) Macleod.

Insulin takes its name from the Latin for “island” and was first identified in 1869 by Paul Langerhans as a hormone produced by the pancreas to regulate blood sugar levels. Hundreds of scientists had tried – and failed – to isolate and extract it from animals.

On May 17, 1921, Banting started operating on healthy dogs. The aim was to remove the pancreas, grind it down to create an extract and then inject this into the dog and measure any recovery. The very first – No. 385, a brown Spaniel female – died within a week.

Later experiments proved more successful. Cattle provided better pancreatic material, but the challenge was to purify it and step up production. In January, 1922, Leonard Thomson, aged 14 and mostly skin and bone, became the first diabetic patient to be injected with insulin. The first dose failed, but he eventually did recover.

This became a massive story around the world. In October, 1923, the Nobel committee announced that Banting and Macleod were to share the Nobel Prize for medicine. Banting had yet to turn 32. He was, and still is, the youngest recipient of the medicine prize.

Banting shared his cash prize with his assistant Charles Best and Macleod split his with James Collip, who was vital to the successful production of insulin.

But instant fame brought a nasty aftermath of angry feuding. Banting was furious at having to share the prize with Macleod and let everyone know about it. Later research by Canadian historian Michael Bliss unravelled the truth – without Macleod’s constant support and advice, Banting’s experiments would have ended up as forgotten failures, along with all the rest.

Macleod returned to Scotland in 1928 taking up the Regius Chair of Physiology at Aberdeen University and happy to escape the public infighting of Toronto. As he left, he shuffled his feet with the words: “I’m wiping away the dirt of this city.”

Both he and Lawrence were former pupils of Aberdeen Grammar who had gone to study medicine at Aberdeen University.

Back in London, Lawrence had embraced his reprieve by embarking on new career as a diabetic specialist. He became one of the world’s foremost authorities on the disease.

He still took risks – using himself as a guinea pig to test out insulin dosage and tolerance. His research explored the various forms of the disease, type 1, and type 2 (which became clearer in the 1930s), childhood and in pregnancy.

Lawrence worked wonders with his patients. Despite his bow tie and white coat, he also had oodles of empathy for them from his own experiences. In 1925 he wrote a book, The Diabetic Life, to help patients and doctors understand the condition. It proved to be hugely popular.

Charles Best was a close friend – attending his wedding and acting as godfather to his first child. Among Lawrence’s private patients was HG Wells, the celebrated author of The Time Machine and War Of The Worlds, with whom he had also developed a strong friendship.

By 1933 Lawrence’s diabetes clinic at King’s College Hospital was in desperate need of more space. Wells wrote a letter to The Times appealing for funds which duly poured in. This prompted a second letter – this time to set up an advocacy and self-help group for patients – the first of its kind for any health condition or disease.

The Diabetic Association was born – later the British Diabetic Association and now Diabetes UK.

From the outset, it funded new research projects. Its first grant of £50 went to a young doctor who had fled the Nazis in Berlin to study under John Macleod.

Hans Kosterlitz rose to become professor of pharmacology. In his retirement, he set up a team to study addictive drugs. It was supported by the US government, which then had serious concerns about Vietnam veterans returning home hooked on heroin.

The Aberdeen group headed by Kosterlitz and John Hughes made a spectacular discovery – what became known as endorphins, the natural opiates naturally produced by the brain which give people the buzz from exercise and ease the pain of severe trauma.

Their paper, published in 1975, was slightly ahead of American colleagues engaged in similar research but they got on well. There was none of the rancour that followed the discovery of insulin.

Kosterlitz, like Lawrence, received many prizes and plaudits in his lifetime. He didn’t win a Nobel prize. But his son, Michael did – sharing the prize for physics in 2016 with fellow Scot Michael Thouless, and Duncan Haldane.

Lawrence, who twice turned down a knighthood, died in 1968.

Experts fear diabetes timebomb with millions of UK cases still undiagnosed

The medical pioneers behind the world-changing research on insulin could not have predicted the surge in diabetes.

There is still no cure and insulin remains the mainstay treatment for type 1 diabetes to keep patients alive – 100 years after its discovery.

Type 2 diabetes is now treated with metformin and other drugs and can be managed and even reversed through careful management.

Deaths across the world from the complications of diabetes increased by 70% between 2000 and 2019. Diabetics also have a significantly higher mortality from Covid-19.

It is all linked to the obesity epidemic, with experts suggesting up to 90% of cases are mainly caused by an unhealthy lifestyle and diet. Diabetes is widely undiagnosed in many and, by 2025, Britain will have an estimated 5.3 million people living with the condition.

Diabetes UK released figures this month showing diagnoses have doubled in the past 15 years with a record 4.9 million patients in the UK – more than one in 10 over-40s.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Shutterstock / Orawan Pattarawim

© Shutterstock / Orawan Pattarawim