The venue was a folk club in a village hotel in rural Aberdeenshire. The crowd might have struggled into triple figures. The headliner? A lost legend of country music.

It has been 25 years since Townes Van Zandt played her Gadie Folk Club in Insch but Deirdre Macdonald still can’t quite believe it happened at all.

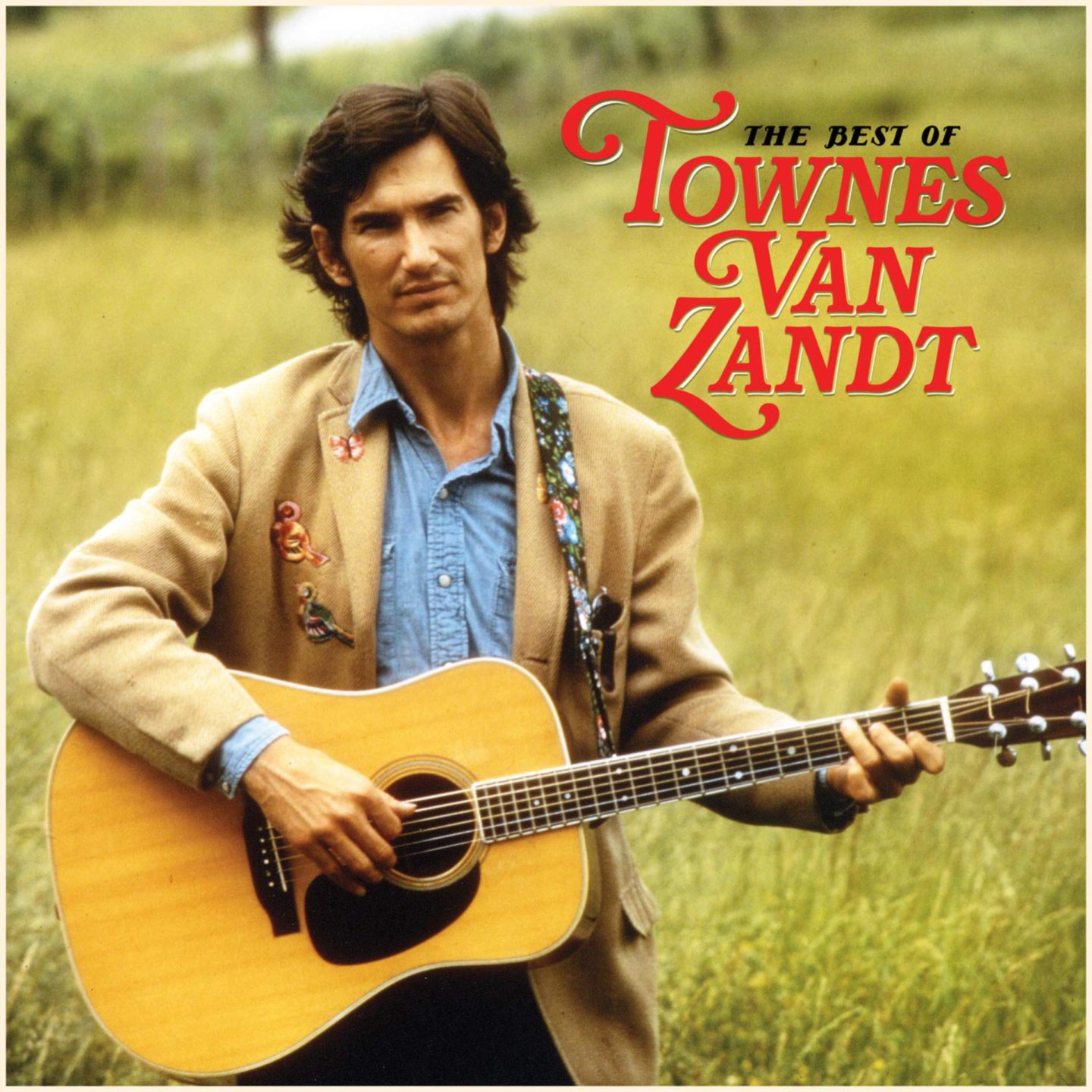

Van Zandt’s songs have been hailed and covered by superstars from Bob Dylan and Emmylou Harris to Willie Nelson and Laura Marling and, despite his musical legacy of melancholic, poetic ballads inspiring generations of performers, his fans continue to lament a sidelined giant of country.

After a careering life, blighted by drink, drugs and mental health issues, Texas-born Van Zandt died at 52 in the early hours of New Year’s Day 1997.

But only a few months earlier, he had played in Insch at the club run by Deirdre and her then husband and musician Iain Macdonald in what would become the first stop on his last tour of Scotland.

It seemed an impossible dream to book one of their musical heroes but on a hot Saturday night, July 20, 1996, Van Zandt took to the stage in Insch’s Station Hotel. Twenty five years on, Deirdre Macdonald said: “We had no idea about his health before he arrived, but it was very soon obvious that all was not well.

“It was a struggle for him, and my son remembers speaking with Townes, and Townes running out of energy and breath to finish his sentences, and it was the same with his performance.

“He would fade from a song, get another breath, and start another number. You were willing him to be OK and be able to sing.”

Townes Van Zandt was born into a wealthy southern family in 1944, and begged his father to buy him a guitar after watching Elvis Presley’s televised performances.

As a young man Van Zandt was diagnosed with manic depression, now known as bipolar disorder, and his parents took the well-meaning but misguided action of submitting him to insulin shock therapy, resulting in damage to his long-term memory and rendering him unable to recall memories from childhood.

He began performing in the mid ’60s and while he had upbeat, fast-tempo songs in his repertoire, he became best known for poetic, melancholic lyrics and stripped-back, fingerpicking guitar playing style.

Drink and drugs took a toll, and by the time he arrived in Insch in 1996, he was visibly weakened.

Iain Macdonald, who died in 2018, was a respected folk musician, and opened the Insch show for Van Zandt, who was so impressed he enjoyed a private jam session with Macdonald on the steps behind the venue, something he rarely did, preferring in his later years to only play guitar when on stage.

He also invited Macdonald and fiddler Louise Mackenzie to open for him the following night at his gig in Perth’s AK Bell Library.

Deirdre Macdonald remembers: “Townes wanted to share the stage with them so that they could do their own thing but Iain and Louise knew a lot of Townes’ songs. So, from a pragmatic point of view, Townes wanted them to help him do a big gig in a concert hall.

“I was in the audience for that show too, and it was so emotional. I feel emotional even now, speaking about it. It was so moving to see him perform despite his ill health. But he pushed through – performing was who he was.”

Harold F Eggers Jr had worked with Van Zandt since the late ’70s and was with him in Scotland that summer as his tour manager. Eggers Jr said: “He was fragile, but had a very, very, very strong spirit.

“He really enjoyed his time in Scotland, he would go down to the Tay River in Perth and spit in it, because someone told him it was good luck.

“We caught a taxi in Insch, and Townes began talking to the driver and telling jokes. Then Townes starts singing, ‘you take the high road, and I take the low road’. The driver said, ‘you’re singing it wrong, it’s ‘you tak the high road’ and then the man sang the whole song beautifully. Townes said, ‘do you hear that? That’s an old soul singing there’.”

Eggers Jr remembered a conversation in which Van Zandt explained why people loved sad music: “He once said to me, ‘blues is happy music’. I said, ‘blues is people crying, it’s not happy music’. Townes said, ‘well, before my next show, go to the front door and watch people walk in, and then when they leave, watch them go out.’

“So I did, and when they came in they had their heads down and weren’t making eye contact with each other. But when they left, they were smiling and hugging each other, and I understood what Townes meant. Blues is happy music because it makes people feel less alone, and that’s what his music was for so many people.”

Somebody Had To Write It, a collection of acoustic Townes Van Zandt songs, is out now

“Guy and I were married, but Townes and I were soul mates.”

They were three burning talents transforming country music in the early 1970s but it was, as we say now, complicated.

The story of Townes Van Zandt’s love triangle with fellow musicians Guy and Susanna Clark is the subject of a new film called Without Getting Killed Or Caught.

Guy Clark is, like Van Zandt, a singer-songwriter legend, famous for tunes such as LA Freeway and The Last Gunfighter Ballad. Susanna Clark was herself successful, and wrote No 1 country hits such as I’ll Be Your San Antone Rose.

They lived together, on and off, they covered each other’s songs – Van Zandt’s version of Clark’s Don’t Let the Sunshine Fool You appeared before his own – and Van Zandt was incredibly close with both husband and wife but Susanna’s diaries, gifted to documentarian Tamara Saviano by Guy Clark, reveal that her relationship with Van Zandt was at times romantic, despite her marriage to Clark. She wrote in one entry:

“Guy and I were married, but Townes and I were soul mates.”

Saviano said: “Guy knew and it was just accepted. Guy wasn’t afraid of the truth. None of them were. He would say, ‘Yeah, this is life. This is what it was’.”

Better than Dylan: Steve Earle’s tribute to songwriting giant

Townes Van Zandt was a mentor and inspiration to Steve Earle, another country singer who has battled more than his fair share of demons.

The singer-songwriter, behind a string of classics such as Copperhead Road and Guitar Town, once said: “Townes is the best songwriter in the whole world, and I’ll stand on Bob Dylan’s coffee table in my cowboy boots and say that.”

He has since admitted that may have been a little hyerbolic but remains a great champion of Van Zandt’s music. He is, however, unsentimental about his failure to win mainstream success.

“When somebody’s as good as Townes Van Zandt was and more people don’t know about it, it’s Townes’ fault,” said Earle. “For whatever reasons, he shot himself in the foot every chance he got. ”

Growing up with a singer-songwriter father in Alabama, filmmaker Margaret Brown thought that she had heard it all when it came to country music but when she heard one of Van Zandt’s songs for the first time, she was blown away.

“My room-mate played me Waitin’ Around To Die. Something about Van Zandt’s music really got to me in a very core, emotional way that’s hard to put into language, which is probably why I made a film about it,” she said.

Be Here To Love Me, Brown’s highly regarded documentary, traced Van Zandt’s turbulent life through interviews with his family, friends and contemporaries.

“When I started making the film, I didn’t quite realise what it meant to be an alcoholic or to have a disease like that and how it just destroys everyone around you. It’s really hard for me to separate his personality from his disease.

“The thing that spoke to me about Townes was: to be a real artist, do you have to get caught up in the idea of artistic purity and genius at the expense of people around you? I think the answer is no.”

Brown explained what she thought was Van Zandt’s legacy: “It’s his songwriting which has been the most influential and the craft in his lyrics.

“He was someone who felt things very deeply, and that’s where the songs came from. The first time I listened to his music was revelatory. It feels really personal, like he is singing directly to you. I can’t think of anyone today who is like him, that type of ‘fall on your sword’ musician.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Ian Dickson/Shutterstock

© Ian Dickson/Shutterstock