In 1961 President John F Kennedy had insisted America was capable of “before this decade is out, landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth”.

The 60s had just six months left when Neil Armstrong and colleagues made it reality.

Having landed on the moon’s Sea of Tranquillity during the evening of Sunday July 20 1969, it would be the wee small hours of the following morning before Neil stepped outside.

He had reported back to Earth: “Houston, Tranquillity Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

It came perilously close to not landing. There were just 20 seconds’ worth of fuel left when The Eagle touched the surface.

Now, 20 minutes after opening the hatch of the Eagle landing craft, he gingerly stepped down and fulfilled JFK’s promise.

Seven minutes later, he collected a soil sample, using a special bag on a stick, folded it and tucked it in his thigh pocket.

He did this so soon just in case there was some emergency and he had to get back in to try to head for home before he could do some proper digging around.

When Buzz Aldrin joined Armstrong on the surface, he described what he saw simply as “magnificent desolation”.

They weren’t there, of course, simply to collect a bit of moondust and admire the views. Even their own experiences would become part of the new knowledge they’d take home to their own planet.

Scientists can learn more about human beings than little green men when they send people into space.

Part of the vast data astronauts bring back to Earth relates to how their bodies coped in such unusual surroundings.

Just a couple of years back, Scott Kelly came back to our planet after 340 days aboard the International Space Station, and he was a different man.

He was two inches taller.

It seems while gravity places plenty pressure on our spines, when we go into space and have no gravity, the opposite happens.

Our vertebrae spread out and stretch, and some astronauts have come home three inches taller. This effect soon wears off.

Scott also reported that the soles of his feet became as soft as a baby’s as he wasn’t using them much but that sleeping is difficult because you are floating in the same position all day.

Bones and muscles deteriorate through lack of use, so if we really are going to have space tourism one day there’s still much research to be done.

For Neil Armstrong on that very first walk, it all felt different from what he’d expected.

Despite the lunar gravity being just a fraction of Earth’s, he said it was “even perhaps easier than the simulations. It’s absolutely no trouble to walk around”.

He and Buzz tried moving in different ways, even two-footed hops, and neither had very much trouble keeping their balance.

They forgot how big their suits were, however, and broke part of the inner craft when they got back in – they had to use part of a pen to get it working so they could head back to Earth.

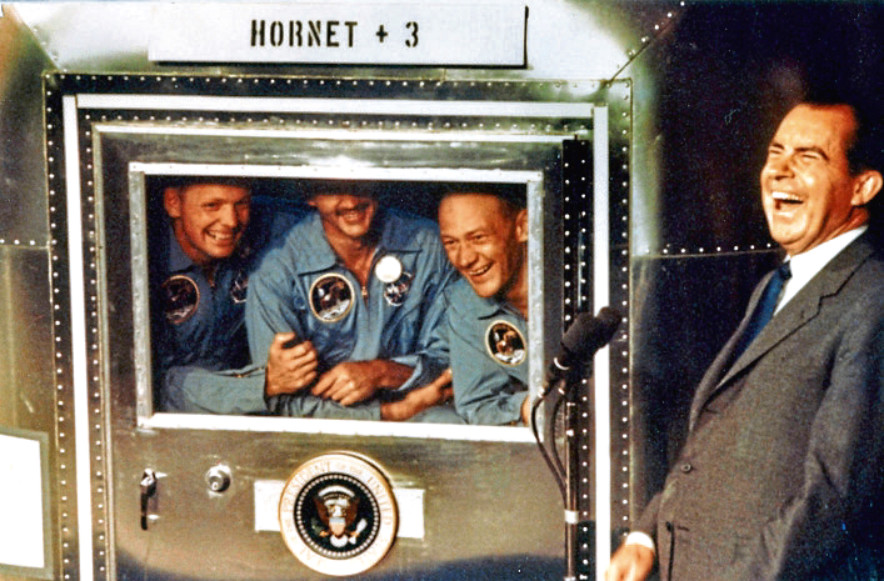

President Richard Nixon spoke to them, saying: “Hello, Neil and Buzz. I’m talking to you by telephone from the Oval Room at the White House. This certainly has to be the most historic telephone call ever made.

“Because of what you have done, the heavens have become a part of man’s world.

“For one priceless moment in the whole history of man, all the people on this Earth are truly one, one in their pride in what you have done, and one in our prayers that you will return safely to Earth.”

“Thank you, Mr President,” Neil replied. “It’s a great honour for us to be here, representing not only the United States, but men of peace of all nations, and with interest and curiosity, and men with a vision for the future.”

They used the Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package, EASEP, to measure moonquakes, and Armstrong walked almost 200 feet from the Lunar Module to take photos of the Little West Crater.

Buzz, meanwhile, collected core samples. Rock samples were picked up with scoops and tongs.

Armalcolite – named after Armstrong, Aldrin and pilot Michael Collins – along with tranquillitvite and pyroxferroite were the three new minerals discovered in their rock samples.

Interestingly, in the half-century since all three have been found on our own planet, too.

For all the breakthroughs, the end result of years of the best brains putting their heads together, it took a 10-year-old boy to help them get back to Earth.

During their return, a bearing at the tracking station in Guam failed, which could have stopped communication.

As they had no time for a normal repair job, station boss Charles Force got his young son to use his small hands to get inside the housing and pack it with grease!

The terrific trio would land in the ocean and be picked up before being put into quarantine for three weeks, in accordance with the Extra-Terrestrial Exposure Law.

Later there were ticker-tape parades, state dinners, Presidential Medals of Freedom, meetings with the Queen, talks in the Soviet Union, stamps to commemorate them, songs written about them, and movies made, books written.

But Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins would not be the last men to land on the moon, even if they remain the best-known.

Apollo 12, just months later, saw the first “Precise Moon Landing”, in the Ocean of Storms. This time, it was Commander Charles Conrad and Pilot Alan L Bean who walked on the surface.

Apollo 13’s landing in 1970 was cancelled after an oxygen tank exploded but it didn’t end in loss of life and the bonus was that we got a fantastic film about it.

Apollo 14 went much more smoothly in 1971. Commander Alan Shepard hit two golf balls on the lunar surface.

He and Edgar Mitchell collected moon rocks and conducted various experiments, and they also broadcast the first colour images from the moon.

Some of their photos showed a suitable landing site for future missions, and Apollo 16 would eventually use one of these.

Many seeds were taken up there, and when brought back grew into so-called moon trees.

The seeds, which orbited the moon but were not taken down to it, were from loblolly pine, sycamore, sweetgum, redwood and Douglas fir.

Although they grew into trees apparently no different from what we Earthlings were used to, they were special because of their famous journey.

Some were presented to famous people such as Emperor Hirohito while one was planted at the White House.

After Alan died in 1998, his wife Louise planned to scatter his ashes but she also died, from a heart attack at 5pm, the exact time Alan always phoned her.

He was the second moonwalking astronaut to pass away, after Apollo 15’s Jim Irwin.

On the subject of health, medical studies in the past few years have suggested that astronauts are more likely to suffer with heart problems.

It is also thought that sudden strong bursts of radiation up there are obviously going to affect their health, and merely travelling outside Earth’s protective magnetic field is a threat, too.

Although Apollo 15 had negative points, too, NASA described it as the most successful manned flight.

Taking place in the summer of 1971, it was the first of the longer stays on the moon.

It also featured the Lunar Roving Vehicle and it accomplished all its objectives, though the mission was marred as the crew took unauthorised postage covers up.

Some of these were later sold by a stamp dealer in Germany – ironic, given that this was one of the few such missions to get a real commemorative US stamp.

The 10th manned mission, Apollo 16, was first to land in the lunar highlands.

Commander John Young and Lunar Module Pilot Charles Duke spent 71 hours, or just less than three days, on the surface.

They drove the Lunar Roving Vehicle for more than 16 miles, collected a large number of samples and did plenty of moonwalking, too.

Apollo 17, in the last weeks of 1972, remains the last mission that saw men walk on the moon.

They enjoyed the longest-ever stay, the most moonwalks and brought home the biggest lunar sample.

On their way to the moon, they also took the classic so-called Blue Marble photograph of our own planet, and it looks as wonderful today as it must have been mind-blowing back then.

They all seem to be focused on Mars and elsewhere these days but what lucky, intrepid, incredible Neil Armstrong did back then is still what millions of us dream of doing ourselves.

n Our fascination with all things space extends to the cinema, of course. Our Top 10 space movies are on pages 30 & 31.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Richard Nixon Foundation via Getty Images

© Richard Nixon Foundation via Getty Images