IN January 1916, with the war 17 months old and hostilities escalating, Britain introduced conscription.

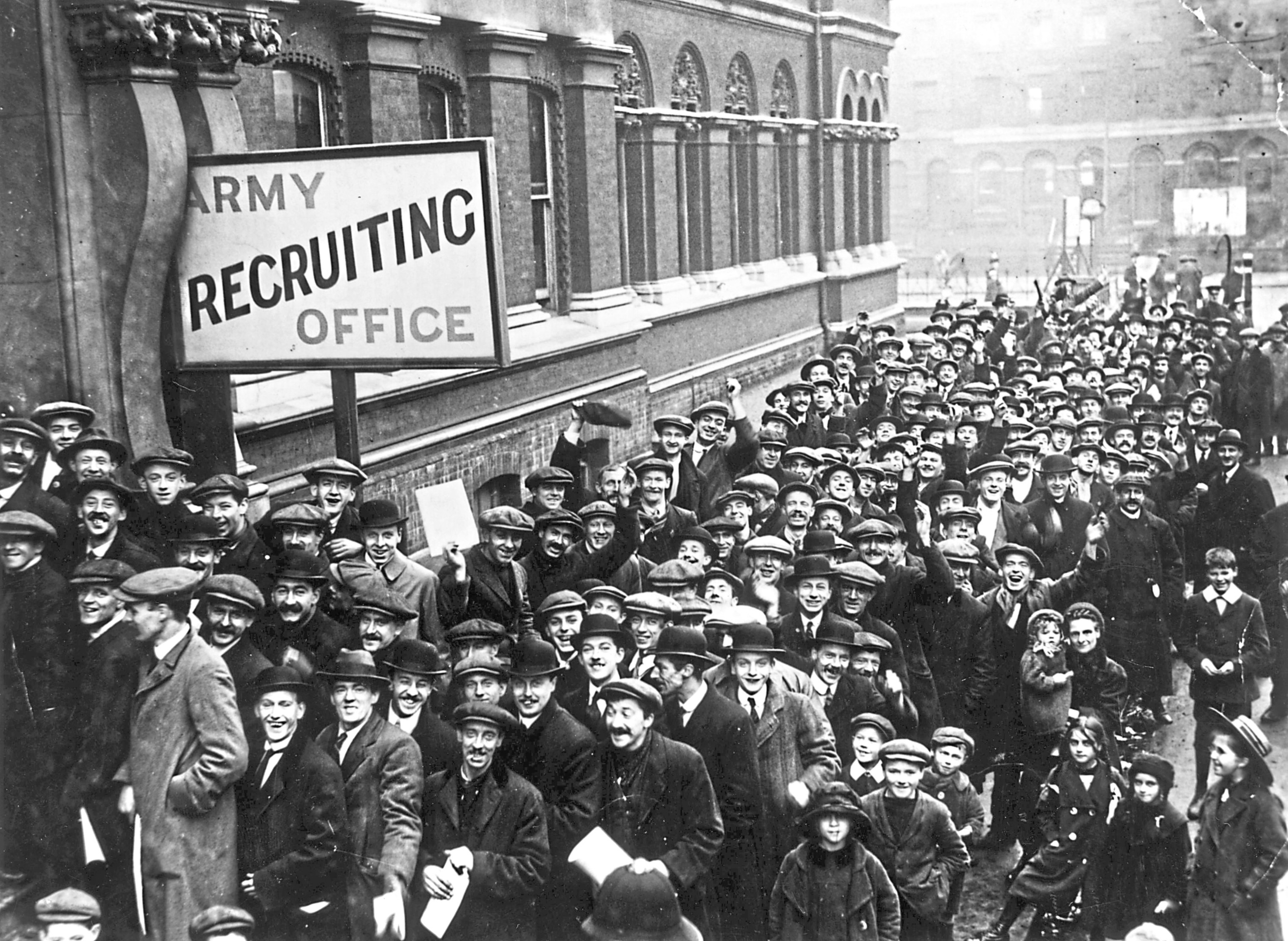

When the Great War began in 1914, the British Army had only 710,000 men at its disposal.

The Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, recognised that it was far too few. The government sought volunteers and, by early 1915, more than one million men had signed up.

However, numbers began to drop and the National Registration Act was created. Initially single men aged 18-41 were targeted. Within a few months, though, conscription was rolled out for married men and the upper age was raised to 56 by 1918.

By the end of the war 2,277,623 men had been conscripted into the British Armed Forces. During the month of June 1916 a record 135,277 were called up.

The introduction of conscription truly brought the conflict home to towns and villages across Britain.

Millions of families suffered the loss of close relatives. Imagine the grief of William and Julia Souls, of Great Rissington in Gloucestershire, for example, who lost five sons.

Such was the extent of the war’s effect that the term “Thankful Villages” emerged, referring to those communities from which no man was lost. Of the 16,000 villages in England and Wales, it’s estimated that just 41 saw all their soldiers return.

Across the Channel, the Battle of Verdun – the longest battle of the war – began in February of 1916. By the time it ended, in December, the Germans had more than 430,000 men killed or wounded and the French approximately 550,000.

Verdun had strategic implications for the Allies because it drastically reduced the number of French troops available for the planned co-ordinated offences and meant Britain would have to lead the push.

At the end of May the British and German navies engaged for the first and only time in the war at the Battle of Jutland. It lasted just two days and involved 250 ships and 100,000 men.

The German High Seas Fleet planned an ambush on the British Grand Fleet in the North Sea.

The British were warned by their codebreakers and though Britain lost 14 ships and more than 6,000 men, while the Germans lost 11 ships and 2,500 men before they withdrew, Germany never again seriously challenged British control of the North Sea.

A month after Jutland the battle that is perhaps most associated with the First World War began.

The Battle of the Somme was a joint operation between British and French forces intended to achieve a decisive victory on the Western Front. For Britain, the battle remains the most painful episode of the war.

The Allied plan to launch an attack in the region of the River Somme was made increasingly urgent by what was happening at Verdun, which also meant the British would take on the main role in the offensive.

They were faced with German defences that had been carefully laid out over many months. Despite a seven-day bombardment prior to the attack on July 1, the British did not achieve a breakthrough and the Somme became a deadlocked battle of attrition.

Over the next 141 days, the British advanced a maximum of seven miles. More than one million men from all sides were killed, wounded or captured.

British casualties on the first day numbered more than 57,000, of which 19,240 were killed, making it the bloodiest in British military history.

The Somme came to represent the apparent futility of the war.

The tide of the conflict turned in April 1917 when the USA declared war on Germany.

President Woodrow Wilson had tried to keep the country out of the conflict and the general feeling was that American men should not risk their lives in a European war.

That started to change in May 1915, when a German U-boat torpedoed and sank British passenger liner the Lusitania in the Atlantic, killing 1,198 of the 1,962 people on board.

Among the dead were 128 Americans and pressure was put on the US Government to abandon its neutral stance.

U-boat operations in the Atlantic were temporarily halted but they resumed in January 1917, making US entry into the war inevitable.

The final straw was an intercepted secret message from German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann to the German ambassador in Mexico proposing that Mexico ally with Germany against the United States and promising the territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.

At first, America had few trained troops to send to Europe.

However, the army was quickly built up and by the end of the war, around two million US troops were in France, to help the Allies.

The Third Battle of Ypres has come to symbolise the horrors associated with the war on the Western Front and is now remembered for the name of the village where it culminated: Passchendaele.

By the summer of 1917, British forces were suffering steady casualties around Ypres and Sir Douglas Haig planned to break out of his army’s poor position and capture an important rail junction a few miles to the east.

Initial attacks failed due to rain, turning the battlefield into a sea of mud.

Although Canadian forces finally captured Passchendaele ridge on November 10, the railway still lay five miles away and the offensive was called off with no strategic gain.

Russia exited hostilities in 1917, after the February revolution toppled the Russian tsarist regime.

In March the German High Command sent exiled Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin and 31 others back to Russia from Switzerland.

The idea was that they would topple the Provisional Government and bring an end to Russia’s involvement.

Widespread war weariness was the major cause of the October Revolution of that year and when the Bolsheviks came to power, their first act was to publish peace proposals and fighting on the Eastern Front ended within weeks.

At first it seemed that Germany had won a significant victory but more than one million men were forced to remain in the east to enforce the treaty.

Despite this, the Germans launched the Operation Michael offensive across the old Somme battlefields in the spring, in the hope that it would end the war in their favour.

British and Allied troops were met with a huge concentration of artillery, gas, smoke and infantry and the Germans achieved unprecedented advances in the first few days, gaining 38 miles of territory and destroying the British Fifth Army.

To better co-ordinate a united defence, the Allies appointed French Marshal Ferdinand Foch as supreme commander, and on August 8 the Battle of Amiens heralded the start of the Hundred Days campaign, a four-month period of Allied success.

The British Expeditionary Force was at the forefront, combining scientific artillery methods and flexible infantry firepower with the use of tanks and aircraft.

After four days of fighting at Amiens, the battle was halted and fresh offensives launched elsewhere.

Though Allied casualties were significant, this set a pattern and a series of co-ordinated hammer blows forced increasingly exhausted German forces back.

With Austria-Hungary on the verge of collapse, there was a chronic shortage of manpower and it quickly became clear that Germany could not win the war.

Back home, meanwhile, there was disillusionment with the Kaiser, the army leadership and the government.

On September 29 Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff told Kaiser Wilhelm II that the war was lost and that negotiations for an armistice based on peace proposals put forward by President Wilson – known as the 14-point plan – should begin.

By October there were mass desertions in the German army and the navy mutinied in November.

On November 7 a group of socialists and anarchists seized power in Munich and a republican Free State of Bavaria was proclaimed.

Within 24 hours many other German cities were in the hands of workers’ and soldiers’ councils.

Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated and the armistice was signed on November 9, to go into effect at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

The peace conference that led to the Treaty of Versailles began its deliberations in Paris in January 1919.

The proceedings were dominated by the French Premier, Georges Clemenceau, and the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George – both pushed by vengeful electorates to make harsh demands of their adversaries – along with Italian Minister President Vittorio Orlando and President Wilson.

In the UK, the end of the war was first commemorated in 1919 with two minutes’ silence at 11am on November 11, on what was then known as Armistice Day.

The remembrance poppy was inspired by the war poem In Flanders Field by Canadian military doctor John McCrae.

The poem acknowledged that despite the fact that buildings, roads, bushes and trees were destroyed by the fighting, the poppies flowered each spring, one of the few plants able to grow on barren battlefields.

It was first published in December 1915 in Punch magazine. After the war, Moina Michael, a professor at the University of Georgia, campaigned to have the poppy adopted as a national symbol of remembrance and, in 1920, the National American Legion agreed.

Frenchwoman Anna E Guérin, who attended that conference, introduced the artificial poppies used today.

In 1921 she sent her poppy sellers to London, where the symbol was adopted by the Royal British Legion.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe