Part Three

Read Part Two here.

IF Alfred Hitchcock had shown a taste for getting inside his audience’s heads, Spellbound took things much further.

He brought in no less a figure than Salvador Dali to create a dream sequence, and the 1945 movie went deep into the world of psychoanalysis.

Gregory Peck and Ingrid Bergman were onboard this time, creating spellbinding chemistry between them, and it’s the tale of a doctor with amnesia being treated by another doctor, Bergman, who promptly falls head over heels for him.

The score featured a haunting theremin, a wonderfully weird instrument that would scare the living daylights out of most people.

Notorious, the next year, had been sold to Hitch, Bergman and Cary Grant for half-a-million dollars, and is a tale written around the Nazis, uranium and South America. The use of uranium, however, attracted an audience Hitchcock didn’t really want – with his lifelong bizarre fear of the police, he suddenly had the FBI watching him.

There was lots of talk about uranium bombs in those days, and it wasn’t long after they described all this as science fiction that Hiroshima and Nagasaki showed it was anything but.

The dawn of the Fifties saw him back to using trains as the ideal backdrop, and 1951’s Strangers On A Train had all the classic Hitchcock elements.

Two men find themselves together and get chatting on a train, with one man suggesting that if two people were to commit each other’s planned murder, they’d both get away scot-free.

If that was a highly lucrative start to the decade, then his trio of flicks with Grace Kelly would prove without doubt that nobody could touch the great Alfred Hitchcock in his current form.

Dial M For Murder, Rear Window and To Catch A Thief were delivered in under two years, each one darker than the other, and all drawing mass cinema audiences around the globe.

Ray Milland was a wonderful villain for the first one, intent on doing away with his wife for lots of money. Alas, she has more about her than he realises, killing her would-be assassin.

Milland’s character then tries to manipulate things to convince the cops that his missus is a cold-blooded murderer.

Kelly was placed opposite James Stewart for Rear Window, which saw him in a wheelchair temporarily.

When he gets bored and takes to observing his neighbours through the window, he grows certain that one of them has killed his wife, and the fun hots up.

With so much of the film shot inside a small apartment, the sheer claustrophobia really got to audiences, and it could be hard to watch a Hitch classic and not feel he was the puppet master, and you were the puppet.

Not a lot of film legends can claim to be as good at that as he was.

For the millions who were as fascinated by Hitch as they were by his movies and stars, the world got a long close-up look at him.

From a decade starting in the mid-Fifties, we were treated to the TV series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and able to enjoy his droll wit, dark humour and obvious intelligence.

With jokes about electric chairs, murders and all things horrid, it was easy to see why he was so good at making scary films – he was genuinely a scary man.

To Catch A Thief, ironically shot on the French Riviera, would be not just Grace Kelly’s last film for Hitch, but her farewell to the business.

By 1956 she would be married to Prince Rainier of Monaco.

Hitch turned to another attractive lady, Doris Day, who would bring him not just a great chemistry but a music award.

Starring alongside James Stewart in The Man Who Knew Too Much – Hitch’s remake of his own 1934 movie – her song Que Sera, Sera clinched a Best Original Song Oscar.

They portrayed a couple whose son is kidnapped, with the climax taking place, as it did in the ’34 version, at the Royal Albert Hall.

If this run of movies had sealed his reputation forever, then 1958’s Vertigo – the British Film Institute’s official Greatest Ever Film – pushed Hitch into the stratosphere.

With Stewart again the main man, and Kim Novak as the ice maiden, it would become the perfect example of the perfect film.

Amazing, now, to think he had fancied Vera Miles rather than Novak, but as Hitchcock explained: “I was offering her a big part, the chance to become a beautiful sophisticated blonde, a real actress. We’d have spent a heap of dollars on it, and she has the bad taste to get pregnant! I hate pregnant women, because then they have children.”

Stewart played Scottie, ex-cop and obsessed with the woman he is being paid to shadow.

Unlike other Hitch classics, there is no happy ending sweetener, the movie concluding in tragedy, and some believe this is the film that shows the real Alfred Hitchcock.

In which case, he was quite an unhappy, pessimistic, bleak man.

A technique called dolly zoom was used in Vertigo to great effect. Copied countless times since, as many Hitch tricks are, it involves zooming in or out at speed, while keeping the actor the same size in the frame – it makes the background and surroundings change size, rather than the human.

How on Earth does a fellow follow something as awesome as Vertigo?

Well, North By Northwest, Psycho and The Birds would certainly help.

Made respectively in 1959, ’60 and ’63, each of them changed film history, grabbed awards and reminded us that nobody could match Hitchcock on top form.

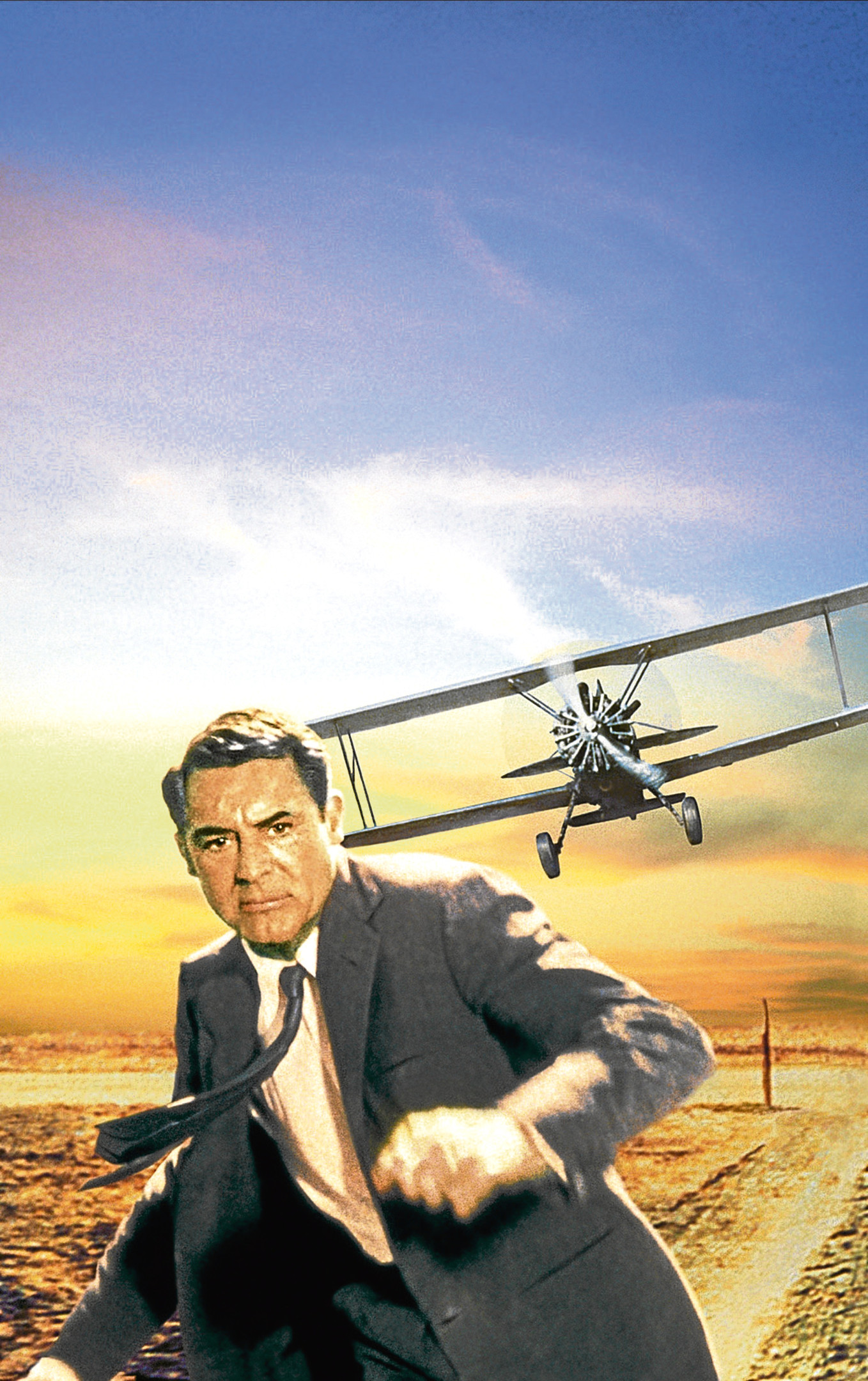

In North By Northwest, Cary Grant was superb as the advertising executive mistaken for a government agent and chased across the country. Eva Marie Saint played a CIA agent, and the scenes in which Grant is pursued by a plane are some of cinema’s most iconic ever.

Not that Psycho was left in the shade – many reckon it has become Hitchcock’s best-known work, and it is hard to argue with that, even if Vertigo is the better film.

So much for folk not liking too much violence, and shower curtain-makers everywhere must have absolutely hated it. To many of us, however, The Birds is right up there with anything we have mentioned so far, as is Marnie which followed it.

You may not know that Hitch had intended doing Marnie first, and it was even announced that Princess Grace of Monaco would come out of retirement to be its star.

She, however, then asked him to postpone it, and Hitch went off to start work on a Daphne du Maurier short story, The Birds.

Tippi Hedren was brought in for her first role, having made her name as a New York model before Hitch set eyes on her and saw a potentially wonderful actress. He wasn’t mistaken.

“I signed her because she is a classic beauty,” was how he put it. “Movies don’t have them any more. Grace Kelly was the last.”

As we now know, Grace wouldn’t come out of retirement for Marnie and Hedren and Sean Connery would do it instead.

As we also know, Hedren’s battle with those viciously pecking, savage birds made a film that matched her looks. Much later, she would claim Hitchcock had been obsessed with her and pestered her.

Alfred Hitchcock’s health would begin to let him down in the Sixties, and his incredible output would inevitably slow down.

It was claimed the studios forced 1966’s Torn Curtain on him, along with another Cold War flick, Topaz in 1969.

But Torn Curtain, featuring Paul Newman and Julie Andrews, is not a movie you would turn your nose up at, while Frenzy, his penultimate 1972 film, still has many of the Hitch touches that we have grown to love.

Despite being tired and often ill, Hitchcock was still working on scripts late in his life, while worrying about his wife, after she had a stroke.

His late knighthood was thoroughly deserved and he loved getting it.

He explained how late it was by simply joking: “I suppose it was a matter of carelessness.”

There was nothing careless about the astonishing run of utterly brilliant films brought to us by the one and only Sir Alfred Hitchcock.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe