The year 1927 was a sensational, historic one for cinema.

For one thing, we got the first official billing of a certain Laurel and Hardy, and if the silent short Putting Pants On Philip wasn’t their biggest hit, it did show how great they would become.

Metropolis, a science fiction fantasy from Fritz Lang, made its debut in Germany and would become an all-time classic of its type, years ahead of its time.

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was founded, too, but one even stood head and shoulders above all the rest.

It was the first massively popular talkie, The Jazz Singer, and if the cinema world had been nervous about how the general public would take to it, they needn’t have worried.

The Jazz Singer was more than twice as successful as its closest rival that year, and would set the standard for years to come.

A lot of pretty good stuff has come our way since, but they still rate it as one of the best-ever American movies, and the half-dozen songs performed by Al Jolson played a big part.

It wasn’t just the first film to have lip-synch singing and speech, but the first feature-length movie with its musical score synchronised, too.

In one fell swoop it heralded the demise of the silents. Many silent stars would simply disappear, while talkies would bring a whole host of new stars.

Produced by Warners and an adaptation of The Day Of Atonement, a short story by Samuel Raphaelson, it told the story of Jakie Rabinowitz. Jakie didn’t much care for his devout Jewish parents’ wishes, running away from home after his father punished him for singing at a beer garden.

Years pass, and he has become Jack Robin, jazz singing star and building a nice career but finding that his background keeps getting in the way.

Best of all, of course, was the fact it had all those songs, belting out the cinema speakers, not to mention the dialogue. For the first audiences, it must have been mindblowing stuff.

The irony was that when Raphaelson had first seen and heard Al Jolson, he said he’d only seen such emotional intensity among cantors, singing in synagogues.

Jolson was 30 at the time, a Russian-born Jew himself, who performed in blackface.

“I shall never forget the first five minutes of Jolson,” Raphaelson recalled. “His velocity, the amazing fluidity with which he shifted from a tremendous absorption in his audience to a tremendous absorption in his song.”

He seemed like the perfect man for the story, and the movie, and they were right.

“Wait a minute, wait a minute, you ain’t heard nothin’ yet,” were the first spoken words, the ones that would have had audiences falling off their seats at the shock of it all.

There had been earlier sound films, but shorts and not done in this way or on this scale. The quality, too, had been poor, but not now.

Those mass audiences would be astonished at the surround sound speakers and 3D movies of today, the stunning computer-generated effects and all the rest of it.

But, in 1927, they had never seen or heard anything like The Jazz Singer.

Not that the silent movies just rolled over and died in that pivotal year. Wings, a silent First World War movie, would become the first and only silent to win the Best Picture Academy Award, and it was pretty revolutionary itself.

For one thing, it was one of the first films to show two men kissing. For another, it was one of the first to show nudity! In 1927!

Gary Cooper, still in his 20s, had a part, and it helped launch him on a major film career.

In a time when it took a month to make a film, this one took nine months, and quite a nine months they were. There were many sordid tales of naughty goings-on behind the scenes during its making, and they also went to amazing lengths to capture unplanned action, with over 20 men given special handheld cameras and told to film everything, just in case something good happened.

The nudity was when men undressed for physical exams before going to war, and in one scene an actor had to drink Champagne and ended up genuinely drunk in the film.

The aerial fight scenes received heaps of praise, and it really was a brilliant film, even as the silent era was ending.

Although in 1928 the majority of hit films were still silent, there was a soundtrack to one very special movie.

Steamboat Willie, courtesy of the geniuses at Disney, marked the official debut of Mickey Mouse, and if anything deserved sound effects, music and dialogue to be added, it was this one.

Al Jolson once again led the year’s biggest hit, The Singing Fool. A mix of silent and talkie, and again from Warners, it was once more built around song.

Jolson was Al Stone, a singing waiter with numbers like I’m Sittin’ On Top Of The World.

Although Al finds success, he soon discovers that for every great day there’s a horrible one to follow. A gold-digging showgirl breaks his heart and he soon finds himself skint and alone.

By the time he has lived on the dark side of the tracks and been plucked back to fame by his friends, Al finds that his beloved son Sonny Boy is dying in hospital.

Inspiring songs and tearjerking storyline helped give Jolson and Warners another huge hit.

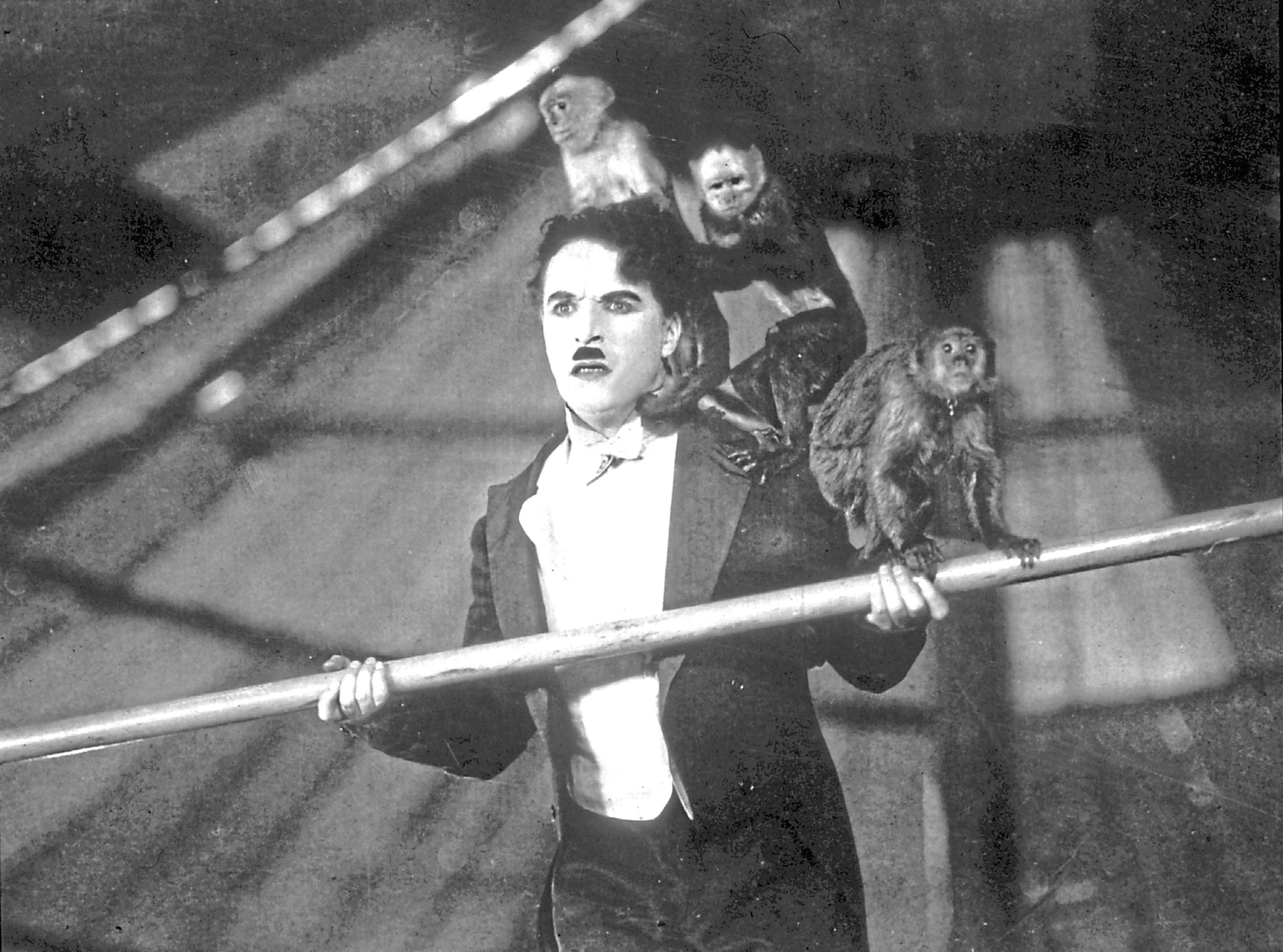

Charlie Chaplin might not have much in the way of songwriting skills, but he could do just about everything else to perfection.

For 1928’s second-biggest film, The Circus, Chaplin wrote it, directed it, produced it and starred in it. If you think Charlie found it all easy, this was not a simple film to complete.

There were problems piling up, not least a studio fire, and then Chaplin was rocked by the death of his mother and the ongoing bitter divorce from his second wife, Lita Grey. He also had the tax folks on his tail, and these horrors combined to stall the movie for eight months.

In it, a circus ringmaster hires the Little Tramp as a clown, and if life had seemed hellbent on making Chaplin miserable, the film delighted his millions of fans.

The Circus remains one of the highest-grossing films of all time.

By 1929, Hollywood had embarked on a mad rush to go all-sound, and the silent era really was at death’s door, despite the silent wonders of stars such as Chaplin.

It was another revolutionary year for cinema, with one of the year’s talking points being the first film to have an entirely black cast, for a movie named Hallelujah! It was The Broadway Melody, however, that stole the show as the year’s biggest flick.

The first sound film to clinch a Best Picture Academy Award, it was also one of the first musicals to feature a Technicolour sequence.

Before long, every self-respecting musical movie would have to have such a sequence. Sadly, though, that sequence from Broadway Melody is now lost and just black-and-white versions remain.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s very first musical, it was also cinema’s first all-talking musical.

Give My Regards To Broadway and You Belong To Me were among its many classic songs.

Today’s producers would be horrified to learn that they made such a movie on a trial-and-error basis.

They would film scenes, play them back to hear how the sound was, and then film the same scenes again with sets changed around to alter the sound and fix any anomalies.

A short scene with Bessie Love playing a ukulele, for instance, took three hours. Thankfully, they were able to record the full orchestra just the once, and play back the recordings for later takes, rather than paying every orchestra member for countless hours of overtime.

The whole Flapper era, which would soon disappear with The Great Depression, was captured in Gold Diggers Of Broadway, 1929’s other top movie.

An early version of Tiptoe Through The Tulips, later made famous all over again by Tiny Tim, was one of the featured musical highlights.

Sadly, like other great movies from the 1920s, much of this film is now lost for all time, and what you’ll find out there in internet land is a shorter version.

It’s still worth a look, though, especially as some of the stars and the people behind the cameras had worked all night and all day, trying to capture the perfect sound by filming the same scenes over and over again.

Like many of the best movies in that amazing decade, they learned as they went along, but the fantastic films of the 1920s would set a very high standard for decades to come.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock

© Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock © Moviestore/Shutterstock

© Moviestore/Shutterstock