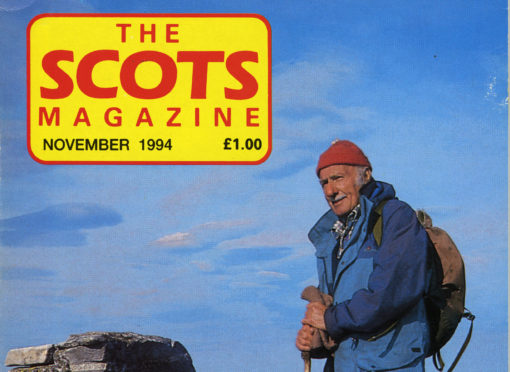

His trademark red bobble hat was a beacon followed by generations of Scots into the country’s wilderness.

Author and broadcaster Tom Weir, the great champion of the country’s outdoors, wrote a monthly column for our sister publication, The Scots Magazine, for more than 50 years with the first published 70 years ago this month.

The magazine’s editor, Robert Wight, said: “The love Tom had for history, landscape and culture shone through in his articles, but what transcended all of that was his love of people.

He had a great turn of phrase, was a great writer and remains an inspiration.”

Here, in his debut article, Tom describes a trip in north-west Sutherland and his descriptions of wildlife, weather, scenery and sense of accomplishment after days in the great outdoors set the tone for the many articles to come.

After taking the train north, his group reach the Reay Forest and some of Scotland’s most rugged landscapes…

Rain met us on the pass, and in storms we climbed into this stony wilderness, to look down at last on Loch Dionard and its great crag. Up here we sat to watch the play of light on Meall Horn and Arkle, and speculate on possible routes up the massive face that lay before us, a thousand feet of it waiting to be explored.

This upper part of Strath Dionard is very heavy walking, and we were glad after a mile or two to strike a track which led us to the promised hut whose location we had plotted on the map. Two camp-beds, a little table, and stove made up its furnishings, and the place was spotlessly clean. We lost no time in brewing up.

The stove must have been giving off paraffin fumes, unfortunately, for I awoke next morning with a headache and a feeling of listlessness. The others complained of a similar feeling, which was a pity, for it was a marvellous morning with the sun shining and the river reflecting the rolling clouds. All the tops were showing off their fancy colours to great effect, but it was a crag marked on the map, A’ Cheir Ghorm, which held our interest, a pyramid of grey rock offering a climb from the corrie floor to the crest of a narrow ridge.

Having breakfasted on trout we made off to inspect that fine face at close quarters. But the rain beat us to it, indeed snow was falling as we tied on the rope below the chosen start. It was too cold to continue on rock of this standard, so we traversed left to where the angle eased a bit, and reached the top by an interesting route.

Now that the climb was over the weather began to improve. Below us Coire Duail with its ice-worn slabs was like a Cuillin corrie. Loch Eriboll was blue as the patches of sky between drifting clouds. Shadows floated over the green patches by its shores, a contrast to the velvet grey of Conamheall and the wild rocks stretching to the face of Ben Hope and its snows.

We made our way over the narrow ridge, rejoicing in the fine conditions. Lord Reay’s Seat was a tooth of rock we had to visit, and from it we watched snow showers expend themselves to reveal the triple heads of Suilven, Quinag, Canisp, and in the far distance An Teallach. West the high hills of Harris, and even the Cuillin, were visible on the vivid sea. Against this wonderful horizon miles of silvery clouds floated. From Rudha Stoer to Eddrachillis Bay and Handa, the coast was just a mass of sparkling lochans and silhouettes of headlands and islands. Descending we had a surprise encounter with an eagle, and had a view of the great bird from a distance of about 40ft.

It was grand out of the wind that colourful evening. On the corrie floor, among the piled boulders, cushion pink and roseroot were blooming, particularly welcome for their delicate beauty in this sterile landscape.

I know of no other area in Scotland so barren of life. During a walk the following morning I heard only a ring ouzel calling from where a couple of rowan trees grew from some rocks. I saw three greenshank in courtship pursuit, two or three pairs of sandpipers, and a wheatear, meadow pipit and cuckoo. That was all.

The only signs of spring in this place are the return of a few birds to the glen and the appearance of the little flowers of the bog-buck bean, lousewort, milkwort, tormentil, roseroot, and a few Alpines.

We packed up, cleaned the bothy and crossed to Gualin House, where our depot of stores awaited our collection. We had never met the people, but they lost no time in providing us with tea, and all too soon we had to cut our ceilidh as the mail car drove up to take us to Keoldale, whence we were to ferry over the Kyle of Durness.

“Just wave a hankie,” the car driver told us, “and the ferryman will be over for you.” As he was taking us across, the ferryman invited us to camp near his house, at a fine clearing on the edge of a birch gully above the sea. Soon we had the tents down, a floor of bracken laid, and a meal on the go.

Rain woke me in the night, but it dawned fine, so we were up and away early to go at last to Clo Mor. Our luck was in, for we got a lift by tractor to within a couple of miles of our cliffs. Turning north, we followed the stream, knowing that a mile farther on we would come to the sea. Kearvaig Bay was as dramatic as the Clo Mor; a little curve of silver sand, a cottage, and beyond it rollers crashing in mushrooms of spray against rock skerries and cliffs. Kittiwake gulls were a fringe of white on a square-topped skerry, ring plovers ran about our feet, and on the sea were hundreds of swimming birds, eiders, razorbills, guillemots, shags.

The whole impression was of colour and movement, excitement and noise; blue sea and sky, silver spray, great cliffs of wine-red stone, and the beat of waves and the crying of birds.

At once we were among nesting birds. Puffins dodged out of burrows, scurrying away, black wings flickering, red legs hung out behind, and in front that remarkable ornament which can only be called a “beak,” not a very teetotal one either. On the skerries and cliffs the ledges were crammed; razorbills on the lower tiers, fulmars on the upper, and everywhere, going in and out of burrows, puffins.

How can I convey the thrill of a coastline so full of movement that one cannot take in any portion at a glance? Standing on the edge of these cliffs, close on a thousand feet high, one is hypnotised by the very act of looking down. Far below is the sea, churned to milk and showering columns of spray as the waves strike a half-submerged skerry. Nothing we meet on mountains is so frightening as the sheer plunge of those walls of Torridonian red sandstone.

This remarkable climate of ours! We spent a warm evening in the tent with a pleasant sunny morning following. We went exploring for birds, beginning with the hill Beinn an Amair and crossing the bog to Loch Airidh na Beinne, then down the Dall river. We saw no geese. A pair of greenshank, a few mallard, and an odd snipe rewarded our journey.

We were looking forward to a closer acquaintance with Balnakeil Bay and the sands we had admired at a distance – as fine a sweep of white sand as there is in the whole of Scotland. A dozen whimbrel feeding there was something we did not expect to find. Later we were to see a small party of sanderlings almost on the same patch of sand, wanderers like the whimbrel, halting a little while before flying north to nest over the sea towards the midnight sun.

Then we came to the cliffs of this narrow headland, a miniature Clo Mor. Fulmars were everywhere and eggs or birds packed the ledges. It was good to see puffin burrows again. Under an overhang we could see a buzzard’s nest. It was in a fearfully exposed place, a wonderful eyrie set dizzily above the crashing surf.

On a little lochan was a gullery, a place of clustering marsh marigolds and buck bean. We took 19 eggs of the nesting black-headed gulls, feeling rather guilty about it, although we needed the food. Every burrow of this sandy soil seemed to contain a nesting wheatear.

By a spring of clear water we pitched our tents – too lovely a spot for our last night under canvas. In the dusk the rasping of corn crakes and the whirr of drumming snipe were comforting sounds, but carrying a portent of rain.

We packed up in a downpour to catch the mail car south. On such a morning the run to Lairg was a desolation of boulders and tumbled rocks without grandeur. For more miles than one cares to count the country is bare of vegetation, peat banks laid out with newly-cut turfs being the only signs of human occupation. Little tracks and stony roads leading westwards to the fringe where the last lonely crofters live by the seashore indicated their destination.

The rich farms of Evanton and the green fields, Speyside and its wealth of trees, struck us as strange after the winter of Cape Wrath and the wild hills of Sutherland.

You can discover more about Tom Weir in The Scots Magazine this month with a touching tribute by Scotland’s top outdoors writer Cameron McNeish

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe