TWO senior police officers who led a crime-fighting force announced their retirement last week as a court judgement revealed mismanagement and cover-up at the elite agency.

Police Scotland’s Deputy Chief Constable Johnny Gwynne and Stephen Whitelock, lead investigator at the HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, announced they were leaving their jobs as a potentially criminal shambles at an undercover unit run by the now-defunct Scottish Crime and Drug Enforcement Agency was laid bare.

Both men and their organisations say their decision to leave their jobs has no connection to the fiasco at the SCDEA, once known as Scotland’s FBI when it led the fight against the country’s most serious and organised crime gangs.

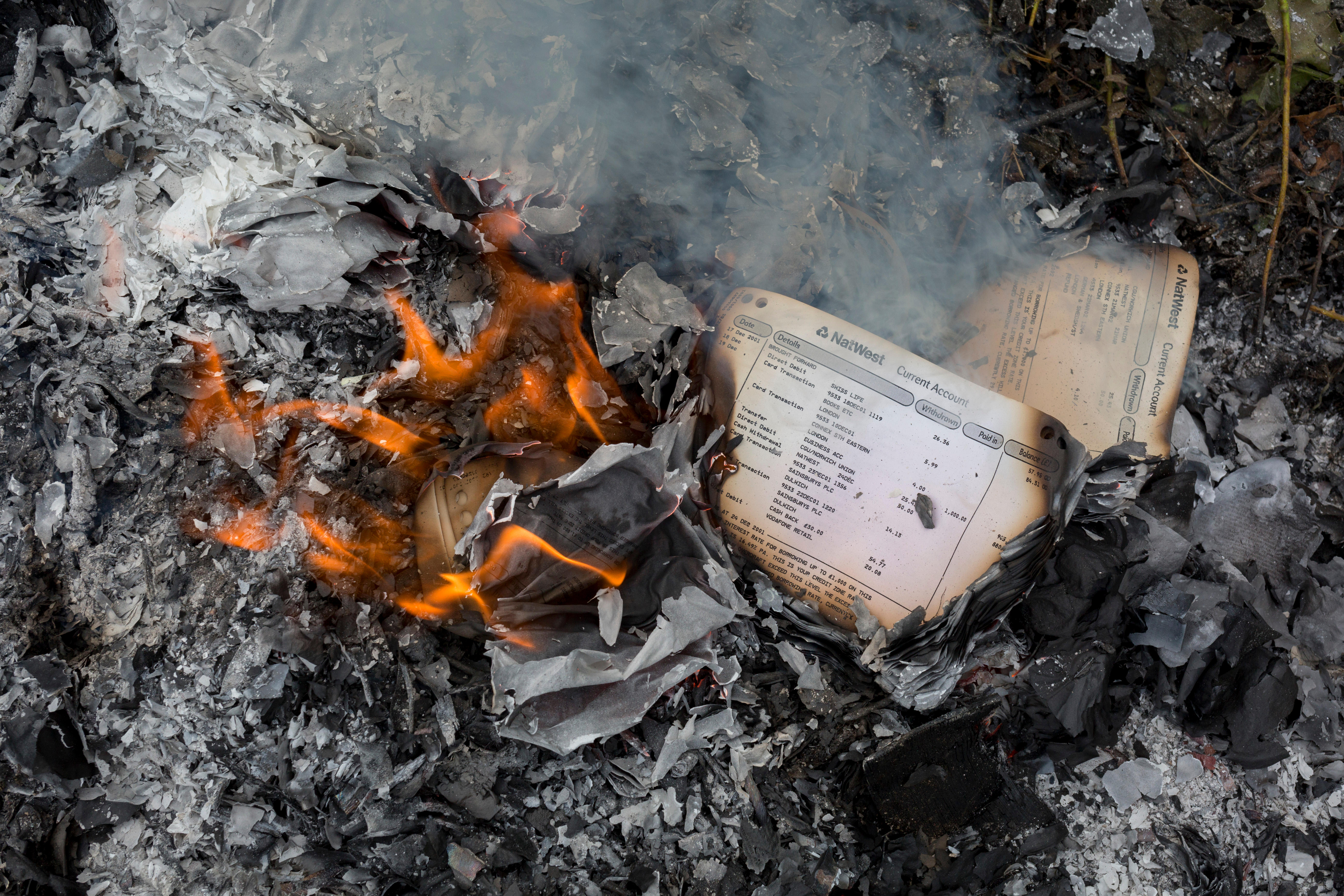

A legal action by a whistleblower, who claimed she was unfairly frozen out of her job for raising the alarm, revealed how senior officers ordered the incineration of secret and highly sensitive files after she reported serious concerns about the finances of a unit managing undercover operations.

Mr Gwynne was number two at the SCDEA at the time and Mr Whitelock was number three.

The agency was then led by Gordon Meldrum, who has already left the police.

The chaos, suspected fraud and cover-up operation prompted calls for a full, independent inquiry yesterday.

There were calls for Police Scotland to ask an external force, from England or Northern Ireland, to investigate or for the Police Investigations and Review Commissioner, who can investigate any police issues in the public interest, to get involved.

Scottish Labour’s justice spokesman Daniel Johnson said: “There is a question as to what body or agency would be competent and capable but given the issues across jurisdictions, it may well be necessary for another police force to carry out this work.”

Liam McArthur MSP, justice spokesman for the Scottish Liberal Democrats, said: “Asking officers to buy an incinerator and burn documents is not normal practice in Scottish policing, and for good reason. It certainly does not speak to a willingness to be open, transparent and accountable.

“I intend to raise this issue with ministers in the Scottish Parliament.”

The mismanagement at the special operations unit emerged in 2011 after the officer, known only as Mrs K, took over responsibility for managing the financial infrastructure that was designed to bolster undercover operations.

Mr Gwynne’s retirement as Police Scotland DCC was announced on Wednesday by Chief Constable Iain Livingstone at a Scottish Police Authority board meeting in Kilmarnock.

Mr Livingstone said: “Johnny and I have been good friends and colleagues for many years and we have worked very closely ever since his return to policing in Scotland.”

The next day a ruling by Lord Brailsford was published which revealed details of a dramatic clean-up operation at the SCDEA when he was deputy director.

Mr Whitelock announced his retiral as lead inspector at HM Inspectorate of Constabulary in Scotland (HMICS) on the same day as the judgement was published.Sources suggest he submitted his notice three months ago.

Mr Whitelock’s judgment and decision-making in removing the whistleblower from the SCDEA was questioned by the judge, Lord Brailsford, who found in favour of the former undercover police officer who brought a damages claim against Police Scotland over her treatment.

Mr Whitelock left the SCDEA in 2013 and went on to work on an HMICS review into undercover policing in Scotland.

The review was published on February 7 last year – the day after Whitelock gave evidence before Lord Bailsford at the Court of Session.

Mr Whitelock told the court that he had ordered Superintendent Ian Thomas to carry out a “review” of the discovery of paperwork at covert premises “to ensure they hadn’t compromised anything”.

One experienced officer, familiar with the structure and operations of the SCDEA at that time, said the destruction of highly-confidential, potentially crucial documents must now be properly investigated.

He said: “Ordering intelligence officers to go and buy an incinerator to burn documents detailing possible fraud in the unit managing undercover officers is not something that happens every day.

“It is not something that should happen at all.

“There are a lot of questions but the biggest is why was this order given? For what purpose?

“The finances of this unit were clearly in disarray and had been for some time.

“Everything is destroyed so we will never know if there was deliberate fraud or just chaotic management.

“Who was signing the accounts off every year, who was meant to be monitoring this work? Who would want evidence of this absolute mess covered-up?

“This is an astonishing incident and the officers then in charge must now be asked exactly what they knew and when?”

Police Scotland said of Johnny Gwynne’s retirement: “It is not linked to the judgement in any way, shape or form. Absolutely not.”

“I had never, ever, in my life, seen anything like this.”

The documents detailing the secret lives of undercover officers waging war on serious and organised crime were stored, in the language of Scotland’s elite police agency, off-site.

The phone bills and rent receipts, mailbox numbers and bank documents, passports and credit cards supporting their cover stories were held at a secure location, away from Osprey House, the HQ of the Scottish Crime and Drug Enforcement Agency, once billed as the country’s FBI.

Behind the doors of a nondescript unit on a humdrum industrial estate was the meticulously-maintained paperwork. Well, it should have been meticulously maintained. Instead, it was a shambles.

There were bags and boxes of files and unopened mail, some shredded, most not. Beside them lay passports, bank cards, and travel documents in a range of names, some of them linked to undercover operations, many not.

There were bank statements, demands from credit agencies, envelopes full of cash. There was an empty bottle of whisky.

It might have been fraud, it might have been the chaos left by an officer in personal and professional meltdown, an officer meant to be painstakingly building the financial infrastructure around Level One undercover operations, including the infiltration of some of Scotland’s most dangerous gangs.

It is unlikely, however, that anyone will ever know exactly what was found in that unit – if there was evidence of possible crimes, if covert operations were possibly compromised, or if undercover officers’ safety had been risked – because a clean-up operation was immediately ordered with officers told to buy a garden incinerator and petrol and burn the lot.

But, after taking the papers to wasteland in an unmarked car, usually used for surveillance, they were challenged by uniformed colleagues before returning to the HQ of Scotland’s premier crime-fighting agency and setting the documents alight in a car park.

The incident was described by the officer, known as Mrs K, during a revelatory civil action against her former bosses, when she accused them of unfairly forcing her out of the job she loved and putting her under unbearable stress.

She had raised the alarm after taking on a new role and, after visiting the unit, discovering financial documents in names of individuals not linked to any undercover operations.

Her boss Danny Rae, a detective inspector, would describe the scene as a “total disaster” and feared it could risk the safety of undercover officers. When his bosses, Chief Inspector James Reid and Superintendent Ian Thomas visited the out-of-town unit in April 2011, Mrs K said, the place looked as if it had been “completely ransacked.”

She told the Court of Session that after seeing the chaos, Superintendent Thomas said she “must have known about this” and kicked a chair in her direction. She said: “I was told no one will ever know about this.”

DI Rae later told her a decision had been taken that the material “had to be incinerated.” He had “started profusely sweating and pulled his tie to the side.”

After the papers were taken to the HQ of the now-defunct SCDEA at Osprey House, beside Glasgow Airport, Mrs K told the court, she and another officer were told to buy a garden incinerator and petrol.

She added: “I have never ever in any of my life seen anything like this. I was panicking, in real fear, and had no idea who to speak to.

“Two intelligence officers were instructed to put that material in a surveillance vehicle, go to the other side of the river and burn it.

“One of the officers phoned me, panicking, and says ‘What is going on? What is going on? Where have these documents come from? Why are we doing this?’

“That officer knew it was wrong as well. He also told me uniformed police had literally drawn into where they were with the incinerator. I don’t know if that officer declared to uniform police who they were.”

The officers came back to Osprey House and then put the garden incinerator in the back yard, which is where unmarked surveillance vehicles were kept and is concealed from the public.

Mrs K said, at one point, Superintendent Thomas walked to the window and said: “How’s the burning going?”

It was going well but the charred scraps of those burning files have drifted through the years and have now ignited calls for an inquiry to uncover exactly who ordered the unprecedented clean-up and, more importantly, why?

“It is time to review how undercover policing is monitored,” says Graeme Pearson, Former head of Scottish Crime and Drug Enforcement Agency

I am not enthusiastic about the use of undercover officers but acknowledge there are circumstances when, to take forward an investigation into terrorism or organised crime, nothing else will work.

However, policing depends on honesty, integrity and transparency and when officers are selected to live a life of “authorised” lies and deceit without effective management, problems will occur.

Their “Walter Mitty” existence makes it difficult to properly assess and oversee the officer’s wellbeing and their activities.

Oversight of their activities relies heavily on trusting the individual officer’s integrity, maturity and wellbeing in what is often a dangerous and stressful working environment.

In this case an absence of management allowed highly irregular activities to develop unnoticed.

Unfortunately once identified the management responses demonstrated a panicked concern for reputations rather than dealing with the actual problem.

The whistleblower was then left to feel isolated and her welfare overlooked.

Police undercover work is the source of some of the most worrying situations faced by the service and a rigorous reassessment is needed to take account of public expectations and Scots law.

Secret techniques must be protected but rules around welfare and governance need revisited.

Alarm-raising officer hailed by politicians

The former undercover police officer – frozen out of the job she loved after reporting the shambolic, possibly criminal, finances of a special operation unit – was hailed yesterday.

Politicians praised her actions while condemning her bosses for unfairly making her a scapegoat, effectively ending her career and putting her under unbearable stress.

A judge has ruled the actions of the Scottish Crime and Drugs Enforcement Agency were unfair and risked the mental health of the woman, known as Mrs K. She could be awarded up to £1 million compensation after Lord Brailsford’s judgment on Thursday.

She had raised the alarm in 2011 after taking charge of the financial management of undercover operations and found records in chaos, with thousands, possibly tens of thousands of pounds, unaccounted for in the shambolic files kept by the officer formerly in charge.

The detective sergeant, referred to in court documents as DSG, took responsibility for the debts and said Mrs K was not involved. Mrs K was later ordered to buy a garden incinerator so that the paperwork could be burned.

She was later transferred out of the Special Operations Unit to a job in a witness protection unit, and was told it was a temporary move.

However, Chief Superintendent Stephen Whitelock, one of her superior officers, admitted he decided she had no future at the SCDEA.

However, that decision was questioned by Lord Brailsford, who said she was “deliberately misled” about a move to the witness protection unit.

In 2013 Mrs K was granted ill health retirement from the police because she was suffering stress, anxiety and depression.

She brought a damages claim for £1m against Police Scotland. Lord Brailsford ruled in Mrs K’s favour and the judgment said further procedures may be required to assess the compensation she was due.

Police Scotland said it was considering the terms of the judgment.

The undercover controversy

Police watchdog Stephen Whitelock faced conflict of interest claims after he helped lead a probe into undercover policing that found no evidence officers infiltrated campaign groups.

The long-delayed report was published on February 7, 2018, the day after he gave evidence in a Court of Session case which revealed a shambles and cover-up at the crime-fighting agency where he was number three. Neil Findlay MSP believes the incident at a special operations unit running undercover officers, and how the officer who raised the alarm was frozen out of her job, demands investigation.

Mr Findlay said: “How can it be that officers are being ordered to burn documents yet there are no repercussions for those who gave the orders, and the officer who complained has had to face the end of her career and years of torment?

“I want to know why this troubling incident was covered up, and why it was ordered.”

“I can only commend the woman at the heart of this case who has gone out of her way, at great personal cost, to uphold the law.

“Just as it was with victims in the scandal of undercover policing across the UK it seems that some police officers think they can operate with impunity.

“The overwhelming majority of police officers in Scotland do an excellent job and will be appalled at such behaviour.”

Mr Whitelock was head of intelligence at the SCDEA in 2011 when a clean-up operation was launched after a management of an undercover unit was exposed as a shambles.

He was lead inspector at the HM Inspectorate of Constabulary in Scotland until his retirement was announced on Thursday – the day a damning court judgement against the agency was published. The HMIC say the timing was a coincidence and that his notice was put in three months ago. Nick McKerrell, law lecturer at Glasgow Caledonian University, said the Scottish Government’s decision not to follow England and order an inquiry into undercover policing should now be reviewed.

He said: “Public faith in policing will be shaken if it is not made clear exactly who is responsible when things go badly wrong.”

Police Scotland

In articles headlined “Chiefs quit as police cover-up exposed”, published on 3 February, we told how a former officer sued Police Scotland, claiming to have been scapegoated by senior officers after uncovering a shambles at the now-defunct Scottish Crime and Drug Enforcement Agency. We believe the ensuing events, including the incineration of documents, was a cover-up but Police Scotland would like to make clear the judge made no finding in relation to the destruction of documents or whether a cover-up took place. Meanwhile, Police Scotland Deputy Chief Constable Johnny Gwynne announced his retirement in January, the day before publication of the judgement. The force would like to make clear his retirement was intimated to the Scottish Police Authority in December 2018 and, they say, was unconnected to the judgement.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe