They were among the most important artists of their generation.

But it wasn’t their artistic talents that connected the likes of playwright Noel Coward, poet Wilfred Owen and textile designer William Morris. Each of them were also members of one of Britain’s most unusual – and little-known – military regiments, the Artists Rifles.

Established in 1860 by painters, poets, musicians and other artists worried about the threat of a French invasion, the volunteer group saw action in a number of conflicts, from the Second Boer War through to the Second World War.

A number of Scots who went on to have notable careers in the arts, such as portrait painter Sir Herbert James Gunn, also served in its ranks.

Patrick Baty is a former member of the regiment and is now the custodian and curator of its history, with plans to set up a museum in the future. He will give a talk later this month about the regiment’s colourful history and its well-known soldiers in a presentation for Army@TheFringe, which is being held online this year due to the coronavirus pandemic.

“I suppose by definition it attracted people who were left-field, highly unconventional, highly intelligent and extremely irregular,” Patrick said.

“I was as guilty as the next person of suspecting artistic types couldn’t possibly have a soldierly streak, and that soldiers couldn’t be thinking, rational, three-dimensional individuals who could also be creatives, but that’s complete tosh and has always been.

“It was probably an attitude that crept in during the 60s, that artists couldn’t be military. Even today, the regiment has graphic designers, architects and other creatives. In my time, my corporal was one of the finest furniture makers in the country, while my background is the architectural use of colour in historic buildings.

“When I was serving, my colleagues and I weren’t terribly interested in the artists, they were something of the past. But in later years I started to look back and was completely blown away by what an unusual organisation it was, and what a bunch of very interesting men had been involved.”

The Artists Rifles was used as a training regiment in the First World War, supplying 10,000 officers. Of those who passed through its ranks during the conflict, eight were awarded the Victorian Cross and more than 1,000 were presented with gallantry medals.

While it was disbanded in 1945, it was revived shortly after to provide foundations for the SAS Reserve and today its title is carried by the 21st Special Air Service Regiment (Artists) (Reserve).

While some artists in the regiment’s early years might have seen it as a way to advance their careers, it developed into an elite unit. “Lots of young men would have joined because Pre-Raphaelites and presidents of the Royal Academy – household names in artistic circles – were already involved, so to go on a military exercise with someone showing work at the academy was quite a smart move if you wanted to get on,” explained Patrick.

“By the time of the Second Boer War, when they had casualties, only 5% were painters, while 12% were architects and they also recruited from London universities.

“It was very much a middle-class operation, made up of people who would end up as bank managers, county solicitors, doctors and so on. It was never snooty.

“It would have been fun, but there was also a serious military aspect and it became one of the elite, go-to regiments for a young man with time on his hands who wanted to be a part-timer.”

Some artists took to military ways better than others, such as Noel Coward, who was invalidated out. “William Morris, who was a multi-talented person, was a very keen member, serving for nine years,” Patrick said.

“But no matter how much time he put into it, he just couldn’t get his drill correct. He was like Corporal Jones from Dad’s Army – he was the only one turning left when everyone else was turning right, but he was loved by all.

“The painter, William Holman Hunt, was also very keen, but he would get confused doing his rifle drill and was always losing bits and pieces when taking them apart, stopping proceedings while everyone looked for the missing parts.”

The artistic legacy

The creative legacy of the Artists Rifles should not be overlooked, according to the regiment’s historian Patrick Baty.

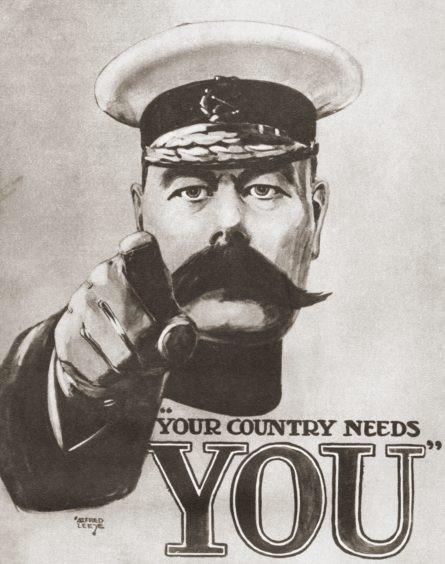

“The Lord Kitchener recruitment poster was drawn by Alfred Leete, who was part of the Artists Rifles,” said Patrick.

“Probably the best known and most moving image of the First World War is a painting by John Nash, another member, called Over The Top, in which around a dozen chaps trudge out of the trenches towards the German front line.

“He took part in that – there were 80 Artists Rifles sent out and 68 were gunned down in minutes. It was really desperate. There are very few unofficial photos to come out of the First World War, but I think the paintings and drawings convey what was happening even better than photographs could,” he says.

Patrick hopes a forthcoming talk for Army@TheFringe is just the start of bringing the story of the Artists Rifles to people’s attention and preserving it for years to come.

He added: “We have a hell of a story to tell, and I’m determined that these men and their tales are not forgotten and they become more widely known. If nothing else, it might encourage people to open up a bit and realise that you can be much more multifaceted – that you don’t just have to be black and white, you can have a second, third or even fourth dimension.”

Patrick’s talk, Arts & The Army: A Relationship Built Over Centuries, is part of Army@TheFringe on August 27. Tickets at armyatthefringe.org

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © The Art Archive/Shutterstock

© The Art Archive/Shutterstock  © Design Pics Inc/Shutterstock

© Design Pics Inc/Shutterstock