THE first time I met Stephen Lawrence’s mother, Doreen, she said very little.

Accompanied by her friend and lawyer, Imran Khan, she had arrived at our editing suite to watch a BBC documentary that followed my time spent undercover as a police recruit.

This was 10 years after her son was murdered and four years after Sir William Macpherson blamed the Metropolitan Police’s failure to properly investigate his death on “institutional racism”.

Before starting my investigation at police college, I had been working hard to prepare my cover, nervous about making a mistake that might jeopardise months of preparation.

Perhaps that was why I was so shocked by the racism, unprepared for the explicit, brutal prejudice, I recorded, virtually from my first day. Worse, this awful racism came not from hardened officers who had patrolled the streets for years but from the newest recruits.

It seemed incredible to me that they thought they should be police officers. It seemed even more incredible that the police agreed.

There were more than 100 of us at the National Police Training Centre at Bruche, Warrington, assembled from forces all over the north of England and Wales.

It was 15 weeks of residential basic training. We were living in each others’ pockets, and I was kitted out with secret cameras.

The death of Stephen Lawrence was central to race relations training given to the recruits. The police service did not want to repeat those mistakes although ome of my fellow recruits seemed less concerned.

Constable Robert Pulling, for example, told me: “He f****** deserved it and his mum and dad are a f****** pair of spongers, and have sponged everything they could get their hands on.

“The Macpherson Report…a kick in the b******* for any white man, that was.”

A week before The Secret Policeman was broadcast in 2003, we arranged to show it to Mrs Lawrence.

I was nervous, unsure of her reaction, knowing her only from a public image of a steely, frank woman, determined to see justice for her son and fully reveal the Met’s failures and the reasons for those failures.

She watched the programme quietly, saying little. When it was over, she said just five words: “It’s just like we thought.”

She did not seem shocked. She seemed the opposite of shocked and, over the years, Doreen Lawrence has found there is little left to shock her.

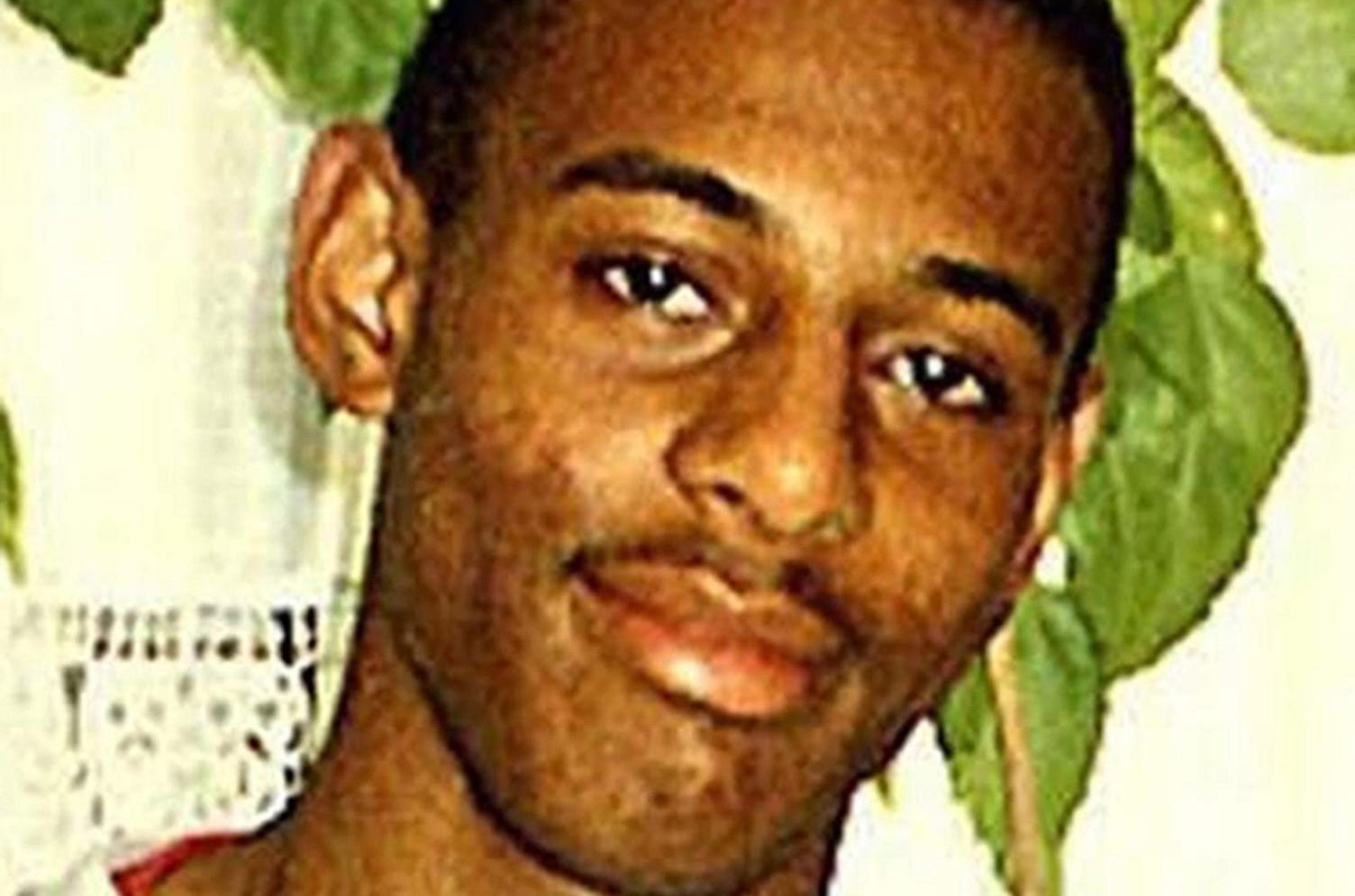

Sunday will mark the 25th anniversary of her son’s murder on 22 April 1993. He was stabbed to death in an unprovoked racist attack by a pack of white youths in London. It would be the most significant murder case in the Met’s history.

Put simply, race relations in the UK fall into two categories: before and after Lawrence. Despite knowing, within 24 hours, the names and addresses of the five men widely suspected of the murder, police failed to make arrests for two weeks, losing the opportunity to capture crucial forensic evidence.

The suspects arrogantly strutted their way through a failed prosecution and an inquest into Stephen’s death, laughing at justice, goading protesters, humiliating the police and piling agony on Stephen’s heartbroken parents, Doreen and Neville.

They would be called out, however, in an unforgettable front page in the Daily Mail simply headlined: “Murderers. The Mail accuses these men of killing. If we are wrong, let them sue us.”

A landmark public inquiry followed, led by Sir William Macpherson, who, in 1999, would conclude that the police failures were not just down to inadequacy.

Simply put, Stephen’s murder was not investigated properly because he was black. Almost overnight, the term “institutional racism” became a phrase synonymous with the Met.

The Macpherson Report would be the starting point for my first involvement in the Lawrence case in late 2001.

At that point I was a newspaper journalist in Scotland but had been invited to join the BBC’s investigations unit to join a secret project – going undercover in the police to expose racism.

The BBC had spent years preparing the groundwork for this deep-cover operation. I was terrified I would not be up to it. But I did my best to prepare. And Lawrence was as its core. The result was the Secret Policeman in 2003, a film that provoked both debate and reform. Two years would pass before I was asked to investigate the Lawrence case again when BBC colleagues asked me to look again at the murder and the police investigation; in particular the persistent rumours of corruption which had dogged the Met’s initial inquiry.

We managed to get our hands on 24 boxes of police files, and spent more than a year with them, locked away in a room in the BBC.

The only time the suspects had ever really answered questions was with Martin Bashir on the Tonight programme in 1999, but this, and another interview by Gary Dobson on TalkRADIO, had given us something to work on – their alibis. And we tore them apart.

Our film, The Boys Who Killed Stephen Lawrence, was broadcast in 2006 and as the title suggests, pulled few punches.

We revealed the claims of whistleblower Neil Putnam that former detective John Davidson had been bribed by the gangster father of one of the suspects to corrupt the investigation, which he denied.

It was high stakes journalism for me, and for the BBC.The Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) launched an immediate inquiry into the corruption claims.

After a year-long investigation, the IPCC concluded there had been no basis for our report and the Met accused us of “sensationalist and irresponsible” reporting. It was the worst day of my career, perhaps of my life, up until that point. But my bosses stood by me.

A month before The Boys Who Killed Stephen Lawrence was broadcast, the Met breathed new life into the inquiry, to be led by a determined detective chief inspector Clive Driscoll and by 2011 they were ready to go to trial.

I was again asked to revisit the case for Panorama, to follow Doreen in the year before the trial of David Norris and Gary Dobson for the murder of her son.

I got to know her as well as any journalist, which may not be all that well at all, but we made a film which, I believe, was a mother’s tale, a story of great grief and huge determination to win justice however long it took.

I was in the courtroom to see Norris and Dobson found guilty, and watched Doreen nearly collapse with emotion. Our film, Panorama: Stephen Lawrence – Time for Justice, was broadcast that same at night when I remember wondering whether those convictions would satisfy Doreen.

Then came an intervention from another newspaper. The Independent, then still in print in 2013, ran a series of reports bolstering the BBC’s 2006 corruption allegations. The result was an inquiry, carried out by Mark Ellison QC, the barrister who had prosecuted the Dobson/Norris trial.

He managed to get underneath the corruption allegations in a way the IPCC had been unwilling or unable to and uncovered more Met failures: inadequate disclosures, lost reports and shredded documents. The force had misled the Lawrence family for years.

Ellison concluded, after all, that there had been “reasonable grounds” to suspect John Davidson was corrupt and, for me his report was a vindication.

For the family, it was just more proof of the Met’s culpability. A quarter of a century on, the murder of Stephen, the police failures to properly investigate his death, and the reasons for those failures have been established.

It is a time to reflect. The BBC will screen a landmark three-part series, starting on Tuesday, retelling a story that has run like a seam through my career.

Is this the end? Certainly, Doreen Lawrence last week said the police should wind down their investigation and the Met wasted no time in suggesting there were no new leads to follow.

But there are still at least three suspects free today who could be jailed if new evidence can be found and there is a National Crime Agency investigation into the corruption claims.

Britain has learned a lot since the violent death of Stephen Lawrence on 22 April 1993; about institutional racism, prejudice, and corruption.

It may have been, as Doreen Lawrence told me, just like we thought, but it was worse than many feared, and there may yet be other lessons to learn.

Stephen: The Murder That Changed A Nation, starts on BBC1, Tuesday, 9pm, and continues on Wednesday and Thursday

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe