The Devil’s Porridge Museum is the most strangely-named museum in Britain.

Not even the fact that it stands on the site of His Majesty’s Factory Gretna gives the game away.

Basically, during the First World War, HM Factory Gretna grew to be the largest munitions factory on Earth, stretching for nine miles from Longtown in England to Dornock in Scotland.

It had its own purpose-built coal-fired power station to provide electricity and a military-pattern narrow-gauge railway network that ran for 125 miles and used 34 engines.

It was built in response to the Shell Crisis of 1915 when the high rate of fire on the Western Front led to a shortage of ammunition for the heavy artillery.

The factory employed 30,000 workers and manufactured 800 tons of cordite a week.

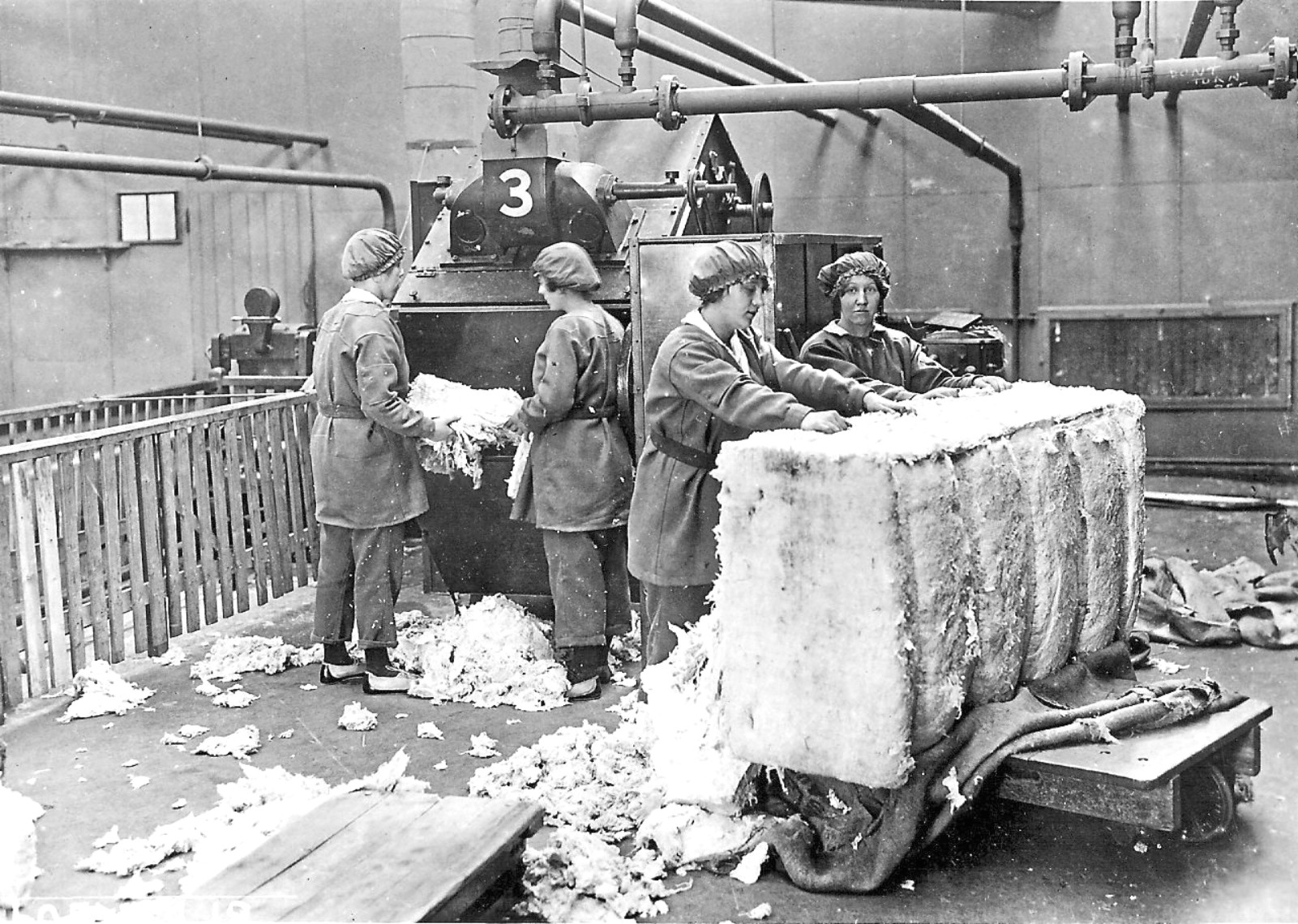

Many of those workers were the so-called Gretna Girls, young women from across the country who made the “Devil’s Porridge” – a term coined by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle after visiting as a war correspondent in 1916.

This was cordite, a volatile mixture of gun-cotton and nitro-glycerine that was mixed in huge nitrating pans, a process that looked like porridge being made on an industrial scale.

Doyle wrote: “The nitro-glycerine on the one side and the gun-cotton on the other are kneaded into a sort of devil’s porridge.

“Those smiling, khaki-clad girls who are swirling the stuff round in their hands would be blown to atoms in an instant if certain small changes occurred.”

Two townships were built at Gretna and Eastriggs to house the 10,000 mainly Irish navvies who built at the factory, and they were followed by people from all over the Empire.

There were explosives experts from South African diamond mines, chemists from New Zealand and Australia, Canadian engineers and the 10,000 navvies.

The legacy of this lives on in the street names of Eastriggs village – Delhi Road, Melbourne Avenue and Singapore Road.

One of the leaders of the factory project was K B Quinan and Prime Minister – and former Minister for Munitions – David Lloyd George said in the Commons: “It would be hard to point to anyone who did more to win the war than Kenneth Bingham Quinan.”

The Gretna Girls, meanwhile, often travelled daily from Carlisle while others moved from Ireland, the Lake District, the Highlands, Tyneside and the Isle of Man.

They were housed in hostels with cubicles for each worker.

The work was dangerous and there were casualties but factory funding paid for a hospital and it also had its own fire brigade.

Life at HMF Gretna wasn’t all hard work, though. There were cinemas, dances, sporting events and romances.

The current exhibition at The Devil’s Porridge Museum is Love In Wartime as the marriage rate spiked during the war, so much so that as well as many marriages, there were also trials for bigamy!

Cordite production ceased with the end of the war in November 1918 and the manufacturing sheds were demolished but the site was “repurposed” as the modern vernacular has it as Central Ammunition Depot Longtown – basically a huge ammunition dump.

The factory site is still owned by the MoD and while access isn’t usually allowed, occasional trips are arranged.

The museum pays tribute to the factory and its workers, as well as the story of the Solway Military Coast during both world wars and beyond – the nearby Chapelcross nuclear power station provided weapons-grade plutonium for nuclear bombs during the Cold War.

Also, the area welcomed hundreds of people during the Second World War including evacuees, Barnardo’s Boys and PoWs while 28 people were killed when a Luftwaffe bomber hit Gretna in 1941.

These stories, as well as those of the thousands of RAF pilots who trained at the area’s many airfields, are told in the fascinating museum.

For more information, visit www.devilsporridge.org.uk

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe