IF you’re anything like me you’ve heard of Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” speech but never actually read it.

Last week I did – every word. It’s awful. More hateful than I’d ever thought.

On Friday, it will be exactly half a century since he made the speech in Birmingham.

I was 18 when I saw the headlines. They said he’d crossed the line. I concluded he was no racist himself but, worried about immigration, he’d made a dangerous speech. He’d given encouragement to some bad people in society.

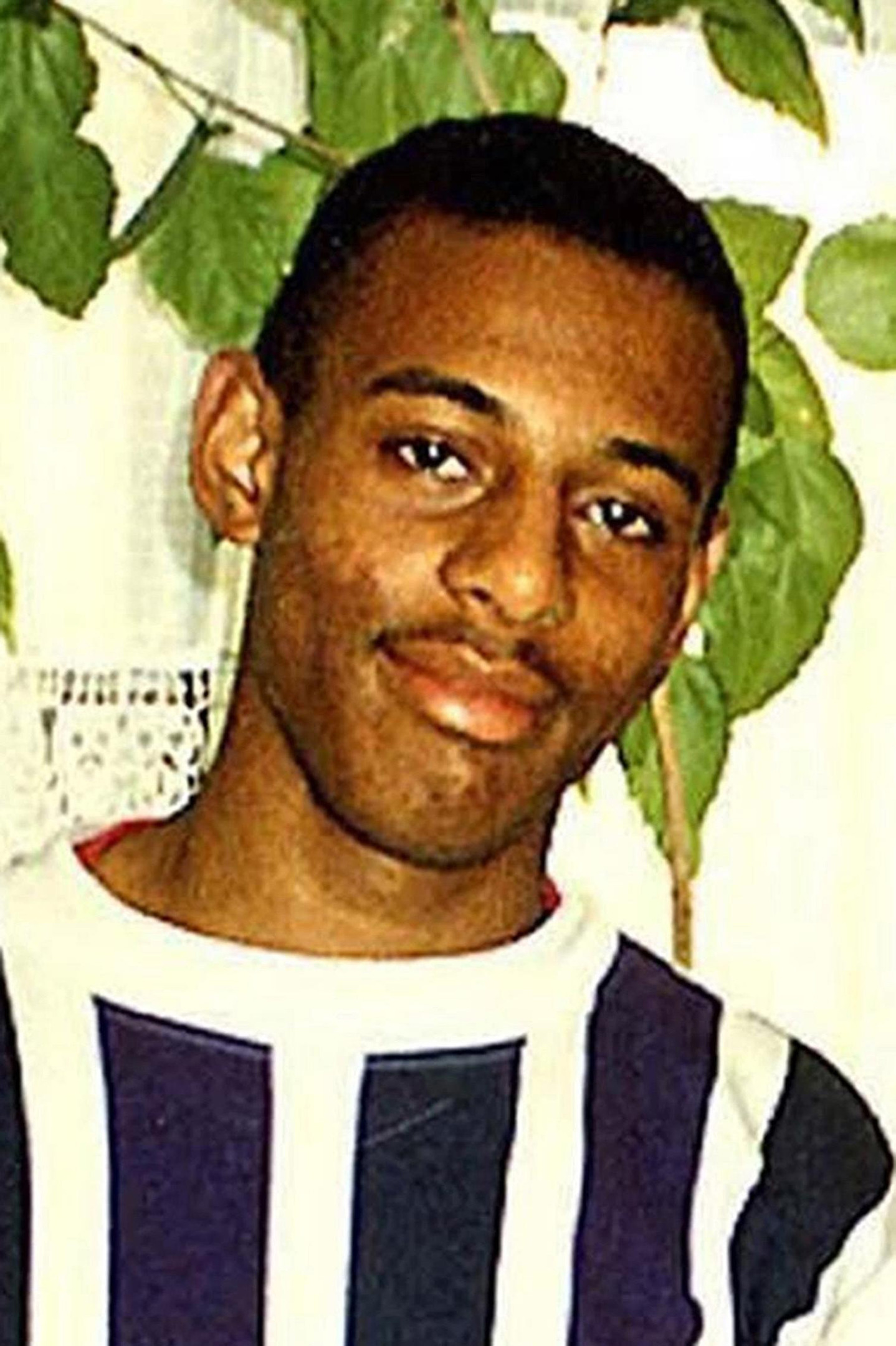

People like the killers of Stephen Lawrence, the 25th anniversary of whose murder is drawing near. Had Powell’s speech started something that monsters like that had taken up?

Read it. Look past his scholarly reference – “rivers of blood” – to Ancient Roman literature.

This was not one, ill-considered line in an otherwise balanced argument. He never once expresses a word of sympathy or understanding for the people called “negroes” by the correspondent he approvingly quotes: he just bangs on, for page after page, about the alleged harm that what he calls “an alien element” is doing to society.

He is, he says, “watching a nation busily heaping up its own funeral pyre”.

Be under no illusion: in Powell’s speech, Stephen Lawrence’s murderers could have found the ignorance and hatred that inspired their horrible deed.

He does this craftily. It’s never actually him saying these things. He quotes other people, people he describes as decent, reliable witnesses.

Then, standing back in apparent alarm, he reminds us that these are their words, not his. He’s only the messenger (he tells us) recounting the direct experiences of others.

These anecdotes, which are the spine of his argument, are wild in their accusations. He quotes someone he met – “a decent, ordinary fellow Englishman,” he says – who told him that “in this country in 15 or 20 years’ time the black man will have the whip hand over the white man”.

He quotes a letter from someone telling him not of her own experience, but of a woman she claims to know. “Eight years ago,” it begins, “in a respectable street in Wolverhampton a house was sold to a Negro …” The letter goes on to describe how she is now “becoming afraid to go out. Windows are broken. She finds excreta pushed through her letterbox. When she goes to the shops, she is followed by children, charming, wide-grinning piccaninnies.

“They cannot speak English, but one word they know. ‘Racialist’, they chant. When the new Race Relations Bill is passed, this woman is convinced she will go to prison. And is she so wrong? I begin to wonder.”

Who are these West Indian children who “cannot speak English”? Powell does not bother to inquire. He takes a kick at Sikhs who want to maintain their own “inappropriate” customs. He throws out wild predictions about future numbers of Commonwealth immigrants, suggesting they will number about 10% of the whole population by the year 2000. This never happened.

Powell then calls for repatriation. He does not say how or who, but wants an “urgent” policy of either paying immigrants to leave, or getting immigrants with family abroad to rejoin their family rather than family members here.

Finally he turns to racial discrimination. Private citizens have a right to discriminate against others on any grounds they like, he says. Anyway, it is “native born” people who are being discriminated against…

“… they found themselves made strangers in their own country … their homes and neighbourhoods changed beyond recognition, their plans and prospects for the future defeated; at work they found that employers hesitated to apply to the immigrant worker the standards of discipline and competence required of the native-born worker; they began to hear, as time went by, more and more voices which told them that they were now the unwanted.”

You cannot hide your eyes from Powell’s intention. He meant to stir. He meant to inflame. He knew who and what he was appealing to: he knew all too well.

Interviewing him not long before he died, I asked Enoch if he’d ever felt embarrassed by who some of his supporters were.

“In politics,” he said coldly, “you take support from wherever it comes.”

Twenty-five years ago, and 25 years after that “Rivers of Blood” speech, the blameless Stephen Lawrence was murdered.

Stephen’s killers will never have read the speech; but they’ll have known Powell’s name and reputation.

And this, too, they will have known: that there was an intelligent, well-educated and respected politician – a man who could read Latin and Ancient Greek – who had given voice to their hatred of black people.

As these brutes will have seen it, Enoch had spoken for them.

For that, he should never be forgiven.

Enoch Powell, a Conservative MP, gave his infamous Rivers of Blood speech to Birmingham Tories on April 20, 1968. His 45-minute warning that immigration would bring violence and devastation to Britain closed with a reference to Virgil’s Aeneid of civil war in Italy when the River Tiber would be “foaming with much blood”. He was sacked as shadow defence secretary the next day and remained a political pariah until his death in 1998, aged 85.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© PA Wire

© PA Wire