When Jemma Reekie became the fastest British woman to run 800m indoors, she was as stunned as the spectators cheering her on in Glasgow.

After stopping the clock at 1 minute, 57.91 seconds, slicing four seconds off her personal best, the 21-year-old Scot tweeted: “I don’t even know what happened out there. I need to try and process this.”

Her talent, indomitable work ethic and appetite for training were all hailed after the stunning race but one question reflected a debate raging across the athletics world for the past five years –what did she have on her feet?

Ever since the Nike Zoom Vaporfly 4% prototype was worn by each medallist in the Men’s 2016 Rio Olympic Marathon – Kenyan runner, Eliud Kipchoge, won the race in 2 hours, 8 minutes and 44 seconds – the evolution of a new breed of “super shoe” has transformed athletics, leaving a trail of broken world records and controversy.

Some see the issue as an exciting and inevitable evolution, while others compare the battle to create the world’s most effective running shoe to an arms race.

“It’s totally changed the landscape of performance in the past five years, and is the biggest equipment change since the advent of synthetic tracks,” said Norrie Hay, high performance athletics coach at Glasgow School of Sport.

“Most of the major records have been broken in the last five years, so it is giving athletes an advantage but we can’t say it’s unfair because these shoes are currently legal. For shoe manufacturers, it’s like a space race to get the best shoe for your athlete, so they get that 1 or 2% improvement to win an Olympic gold, which then becomes marketing gold.”

Starting with road racing in 2016 then track events in 2019, athletes wearing cutting-edge shoes have seen their times and performance level increase.

Nike officially launched its Vaporfly shoe in 2017, claiming it made road runners 4% more efficient by using a combination of a super-charged, super-soft foam sole and a full-length carbon plate. This increased running economy meant athletes used less energy, helping them run faster for longer, especially in the last tiring minutes of a marathon. It has proved revolutionary.

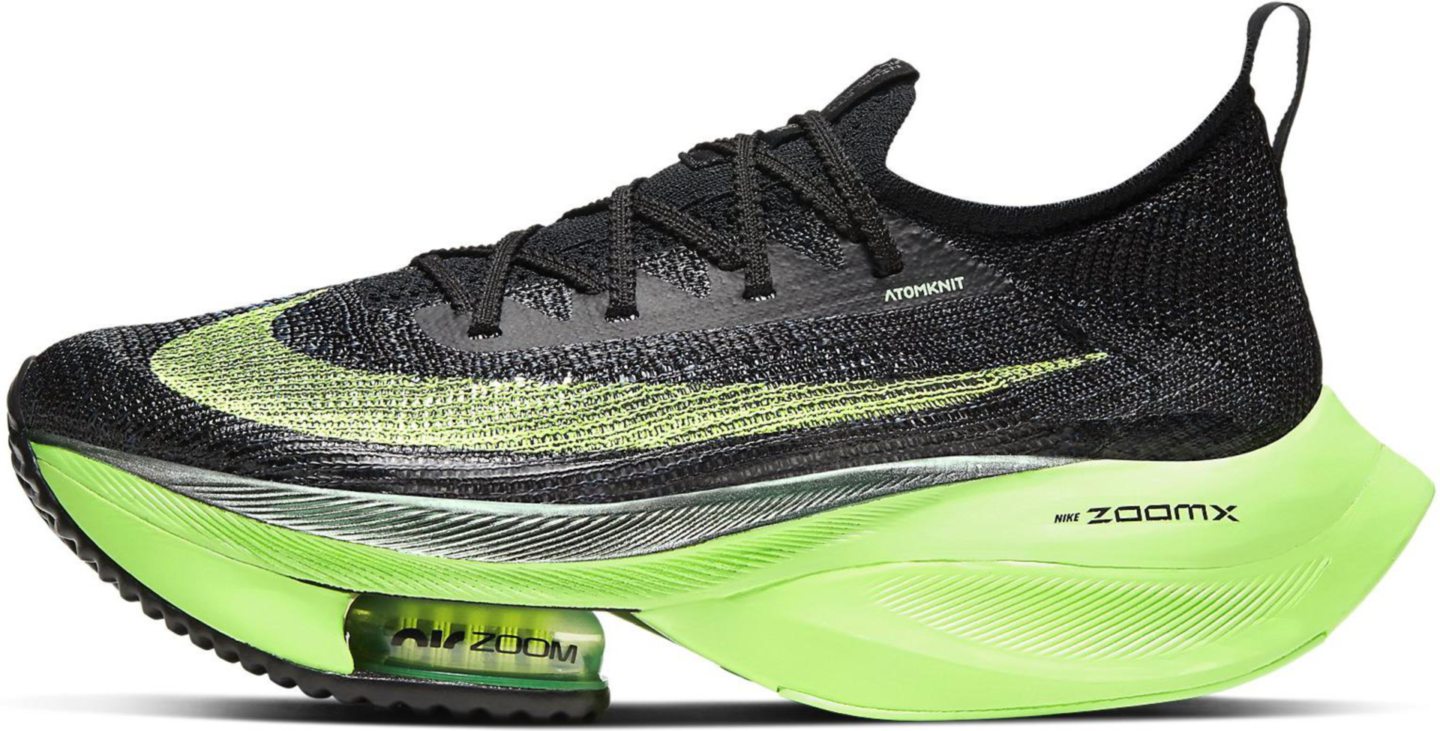

After continued innovations, Nike enjoyed possibly the biggest-ever marketing event for a running shoe in October 2019, when Kipchoge became the first runner to break the two-hour marathon barrier in 1 hour 59 minutes and 40 seconds. He wore Nike Air Zoom Alphafly NEXT% shoes, a bespoke version of the Vaporfly.

In the same weekend, Brigid Kosgei also smashed Paula Radcliffe’s 16-year-old women’s marathon record by 1.21 seconds, again in Vaporflys. Radcliffe said at the time: “It’s just innovation. Same as my shoes were better than my predecessors’.”

Nike’s prototype spikes have had a similar performance-enhancing effect. The Nike ZoomX Dragonfly spikes, billed as the “fastest shoes ever”, were worn by both runners who broke the men’s 10,000m and the women’s 5,000m records in October.

Brands like Adidas, New Balance, Reebok, Hoka and Asics have since launched their own super shoes to rival Nike, going some way to levelling the playing field. While these shoes, and more advanced prototypes, are free to elite athletes via sponsorship deals, they cost around £250 for members of the public to buy.

It’s clear to experts and coaches that advances in running shoe technology is helping athletes push the boundaries of racing performance. Mark Pollard, head of performance at Scottish Athletics, said: “The evolution of technology has impacted most sports. Fina, the governing body of swimming, banned new low-drag swimming suits in 2009 because so many world records were decimated within such a short space of time.

“Whether these shoes become accepted as the new normal or if there’s a significant review, and it goes down the line of the banned swimsuits, will be interesting to see but the feeling is that these shoes are here to stay.

“Innovation has always been part of the evolution of athletics. Running surfaces, spikes and clothing have always progressed and evolved to help people run faster.”

Continuing advances in running shoe technology initially left the sport’s governing bodies scrambling to implement rules to ensure everyone is competing on an even playing field. In April 2020, World Athletics (WA) decided that all shoes worn in competition must be freely available “on the open retail market for four months”. Soles could be no thicker than 40mm and soles with spikes no thicker than 30mm, with other conditions varying from discipline to discipline.

Last August, World Athletics issued a list of approved shoes. In December, it announced prototypes could be used in WA-sanctioned competitions, but not the upcoming Olympics, and could only be worn for 12 months before being made available to the public.

Former Scottish gold-medal relay runner and Olympian Brian Whittle sees this technological leap as inevitable but one that requires strict regulation. “You can’t blame a shoe manufacturer for creating a product that’s too good, or an athlete for wearing them,” he said. “It’s up to the powers that be to create the rules that allow for a level playing field.”

World Athletics president Sebastian Coe, whose 38-year-old British men’s indoor 800m record fell to Elliot Giles in February, has shrugged off concerns about new shoes and track spikes, stating he doesn’t want to “suffocate innovation”.

He said: “I don’t think we’ve reached that point where world records are being handed out like confetti. These things come in cycles. There is a built-in dynamic where shoe companies invest a lot of money into the research and development of shoes.”

In her record-obliterating run in Glasgow, Reekie and her training partner, fellow Scot and 1,500m European champion Laura Muir, wore prototype Nike spikes. The shoes were in line with World Athletics guidelines and would soon be available to buy in shops, legitimising her phenomenal performance.

“When Jemma broke records in Glasgow, she was asked about her shoes but you have to remember that she’s training with Laura Muir,” noted Paul Freary, performance product editor at industry publication Athletics Weekly. “She essentially has the best training partner in the world, plus the best science, facilities, coaching and nutrition behind her. Those elements develop all the time, so you’re always going to see performances increase by certain margins.”

Innovation aside, some fear rapid advances in shoe technology could damage the sport’s reputation and be unfair to athletes. In an interview with Athletics Illustrated last year, Liz McColgan, one of Scotland’s all-time great distance runners and coach to daughter Eilish McColgan, said: “The time has come to cap technological input. Athletes should be on the start line as equals and presently they are not.”

Others are more critical. Eurosport athletics commentator and former British bronze medal-winning middle distance runner, Tim Hutchings, said: “Effectively, these shoes are almost a legalised form of doping because the technology is enabling people to perform way beyond what they would do naturally. Unfortunately, there’s a parallel with steroids in that these shoes offer greater protection and help athletes recover quicker and therefore train harder.

“We hear some people respond to this technology better than others, so the shoes are creating winners and losers before the starting gun goes off.”

Last month, Nike stoked the controversy by failing to release its latest super shoe, the Viperfly, designed specifically for 100m sprinters, last summer as scheduled. Some believe it may reappear before the Tokyo Olympics. Could records like Usain Bolt’s iconic 9.58 second 100m be under threat to an athlete sporting Viperflys?

Norrie Hay, who has coached athletics for 17 years, says the margins are minute: “It could be two years before Usain Bolt’s record falls to someone with a lesser ability than Bolt but with a shoe that gives them a 4% advantage. When it comes to the 100m sprint, the margins are so small that any slight advantage can mean the difference between coming first and last.

“I don’t see any situation where these shoes will be banned. World Athletics might have to tighten the regulations, but these super shoes are here to stay.”

Five years on, experts, coaches, governing bodies and commentators remain undecided on the issue but agree that any advances cannot undermine the sport or competitors.

As Mark Pollard says: “Athletes would feel disadvantaged if they were not wearing these shoes but what you can’t do is diminish their achievements. It’s not like they’re sitting on the couch and then pop on these super shoes to run a world record. It would be a disservice to today’s athletes if we solely concentrated on these shoes rather than all the hard work and dedication they put in.

“Equally, you need to respect those in the past who have produced exceptional performances in what could be seen as weaker technology. World Athletics needs to keep tightening and refining the rules around running shoes as they evolve and data analysis continues.”

How super shoes work

Paul Freary, performance product editor at top industry publication Athletics Weekly, explains the science behind the super shoe: “A carbon fibre plate is embedded in the foam cushioning of the shoe, and that foam is much lighter and springier.

It’s like a rubber ball that rebounds its energy much quicker on the bounce. The carbon plate stabilises that material, so you get a greater energy return. It also stiffens up the forefoot, which creates a bigger lever to help you push off harder and faster.”

Their ability to enhance recovery also offers athletes long-term benefits, he added.

“There’s no rule to what shoes you can train in and, as these materials are so advanced and springy, your legs don’t feel as tired at the end of a race and recovery is quicker.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM