If the landscape did not chill viewers, the drama’s pounding dark heart and horror certainly did.

The BBC’s Arctic thriller, The North Water, a five-part whaling drama set in the 1850s and starring Jack O’Connell as Patrick Sumner who joins the Greenland-bound whaling ship Volunteer as its surgeon, and Colin Farrell as Henry Drax, its psychopathic harpooner – had fans absolutely riveted.

Adapted from Ian McGuire’s 2016 novel of the same name which was longlisted for the Man Booker prize, it was not for the fainthearted with echoes of classic writers such as Mary Shelley and Arthur Conan Doyle whose work has been inspired by the wastelands of ice and snow.

But there are other stories to tell from the Arctic and Elisabeth Gifford has told one of them in A Woman Made Of Snow. It is inspired by the real-life Kellie Castle in Fife and the whalers of Dundee; men like Captain Alexander Murray jnr who took an Inuit bride alongside his Scots wife and who, like his brother John, also a whaling skipper, fathered Inuit children.

Gifford’s mysterious love story opens in the 1940s with Caro Gillan who, with her new husband Alasdair and their young baby, has gone to live with his opinionated mother at their family’s Fife country pile. There, Caro unearths a century-old mystery surrounding a missing Gillan bride.

It takes her to the Arctic where Alasdair’s forebear Oliver, a young ship’s surgeon, fell in love with and married an Inuit girl whom he took home to Kelly Castle and his disapproving mother. The plot twists when a body is discovered in the grounds.

The author said: “A lot of stories about the Arctic are very Gothic. Arthur Conan Doyle, while serving as a student surgeon on a whaler, wrote a ghost story about an Arctic voyage. From early Victorian times, writers have penned tales about the sublime and savage Arctic wilderness and the journey to man’s darkest heart that six months of darkness can cause.

“Mary Shelley, as a girl, spent time in Dundee and would have listened to tales from the whaling captains. At the end of her novel, Frankenstein’s monster flees into darkness across the Arctic waste.

“The Terror (by Dan Simmons) and The North Water continue in this Gothic tradition of man set against extreme taboos. The North Water is very grim. But for A Woman Made of Snow I wanted to evoke the daily lives of the whaler men and the Inuit with whom they worked and lived, forging friendships and even marriages.

“Alexander Murray jnr, born on his father’s Peterhead-registered whaling ship, and brother John, also a skipper, worked for the Tay Whale Fishing Company. Alexander married an Inuit woman called Ooloota and had two children with her. John had an Inuit daughter.”

London-based Gifford, 62, a former teacher and special needs coordinator who became an author a decade ago after gaining a masters in creative writing, revealed: “I have been interested in the link between the Inuit and Scotland for a long time. It began when I was researching The Secrets Of The Sea House, my first novel about the mermaid legends of the Hebrides.

“My son, Hugh, was a doctor in ICU and his wife a paediatrician at Ninewells Hospital. I was going to Dundee quite a lot to help out with my two grandsons and became aware of its whalers and the Inuits.

“The Arctic Bar is where whalers used to go to collect their pay at the end of their six-month voyage. It still has harpoons and pictures of whaling ships on the walls. So I went with my daughter-in-law, who is descended from the city’s Calman shipbuilders, and her baby, to the pub to investigate.

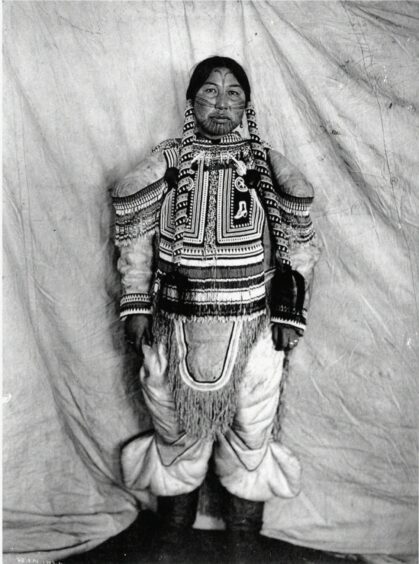

“The McManus Museum in Dundee was also very helpful with my research. It holds many Inuit artefacts, brought back by Victorian whaler men, along with a stunning collection of photographs of Inuit and whaling boat crews, and several diaries written by various ships’ surgeons – usually medical students wanting adventure and funds for the summer.

“The city’s whaling industry lasted longer than in any other whaling port in Scotland and England. With steady work available and a strong church tradition, the whaler men of Dundee were, by and large, sober artisans, though with plenty of the famous ‘wild rough lot’ found in most whaling ports.

“Conan Doyle found the working-class Scots crew he sailed with steady and educated, sober and religious. He enjoyed talking with the crew and relished joining in with hunting expeditions.

“Though given little credit owing to their working-class backgrounds, the Scots whaling captains often knew more about the Arctic than most of the captains sent out on feted Admiralty Arctic expeditions. Dundee whaling crews interacted with Inuit and adopted the polar technology of the Inuit tribes they met and worked with, commissioning sealskin boots and suits for the men for winter.

“Such ‘going native’ was looked down upon by the brave and manly sons of Empire, who set out to conquer the polar extremes. Scott of the Antarctic would pay dearly for such hubris by his refusal to use sled dogs and Inuit technology.”

From the early 19th Century, as whales declined in numbers, Scots ships from Dundee and Aberdeen began to overwinter on Baffin Island and the far side of Hudson Bay.

“They wanted to be ready to begin hunting as soon as the ice broke up,” said Gifford. “Each ship would hire several Inuit or even a whole tribe to supply fur clothes and boots and to help with hunting for seal and whales. In exchange, the Inuit received knives, beads, sewing machines and sometimes their own small boat to hunt the whales for the Scotsmen.

“The Inuit hunter gatherers were surprised to be given three meals a day, even when they were not hungry, and discovered a taste for coffee, cocoa and treacle. They learned to play the accordion and danced Scots reels on deck with the sailors. But there was abuse. Inuit tribes would allow ‘Arctic wives’ for the whaler men, but only for men they respected.”

The Murray brothers overwintered in Repulse Bay with Quebec’s Captain Cromer who took Shoofly as his Inuit wife. Gifford said: “With her bead-braided hair and tattooed face, she went with the permission of her husband and of her husband’s second wife since Shoofly was barren. Up until the 1980s many elderly Inuit had happy memories of their childhood among the whalers, dances on board and good food on great ships.”

Gifford explained: “The storyline about Oliver and his Inuit wife is fiction based on my research, but Kellie Castle is fact, and influenced the book. My husband David’s family lived in St Andrews.

“His father, Douglas Gifford, was a professor at the university and he and his wife Hazel were friends of the sculptor Hew Lorimer and his wife Mary who lived at the castle, now run by the National Trust for Scotland.”

She said Mary had inspired “the make do and mend” attitude of Martha, the mother-in-law in the book. Gifford’s own mother-in-law was part of the inspiration for heroine Caro: “I wanted to write about and celebrate the indomitable women who ot degrees and worked as well as running a home.”

But her exploration of in-law relationships was not borne out of experience. She said: “I read psychologist Terri Apter’s wonderful book on in-laws, What Do You Want From Me, and created the story dynamics from there.”

The theme that runs through the novel is the importance of looking behind stereotypes to understand people as people. It is, according to the author, as applicable to understanding other cultures as it is to family relationships.

She smiled: “I hope A Woman Made Of Snow will serve to bring to life some of these early encounters between Dundee’s Victorian whalers and the last hunter-gatherers of Arctic Canada.”

A Woman Made Of Snow, by Elisabeth Gifford is published by Corvus

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe