A NEW book reveals how the Victorians invented the modern way of ordering and breeding man’s best friend.

One of the co-authors from the University of Manchester, Michael Worboys, tells Murray Scougall the Honest Truth about how the look of dogs was changed forever

What is your background?

I am a historian of science and medicine who became interested in dogs through studying rabies.

Why did you and your co-authors write this book?

We were struck by a previously unrecognised major change in dogs that occurred in the Victorian era.

Before then there were many terms used for dogs – types, varieties, sorts, strains, kinds and breeds. After, there was just one – breed – but this was much more than a word change.

Dog breeds were defined by their physical form, not their function. This was a big deal for dogs. Looks counted for more than ability and temperament.

Quite quickly, the nation’s dogs were remodelled to the new breed templates of anatomical points – and not just in Britain, because breed as a way of seeing and breeding dogs was adopted around the world.

Previously there were a few general types of dog. For example, there were just two types of terrier recognised in the 1840s, 10 at the end of the Victorian period, and 27 today.

What research did you do?

We read books, general and sporting newspapers and specialist journals, paying particular attention to illustrations that revealed changing physical features. We also used the breed clubs’ records.

How were dogs regarded prior to the introduction of breeds?

From the very origins of domestication, dogs were primarily valued for what they did, not their appearance. Working dogs were bred to suit local conditions and pet owners wanted unique individuals, not standard animals.

How quickly did certain breeds become more fashionable than others?

Dog shows drove the invention of modern dog breeds. The very earliest were held in pubs. After dog fighting was banned, the working class turned to rat-catching contests and what they termed “beauty shows”.

After 1860, shows moved upmarket to exhibitions and competitions that rapidly grew in number and popularity. Exhibitors and breeders were known as fanciers.

Competition for prizes and prestige was intense, with champions sold for high prices. Breed fashions changed quickly, as when exotic breeds came in vogue after Queen Victoria was given a Pekingese.

Would a particular type of dog demonstrate an owner’s social standing and class?

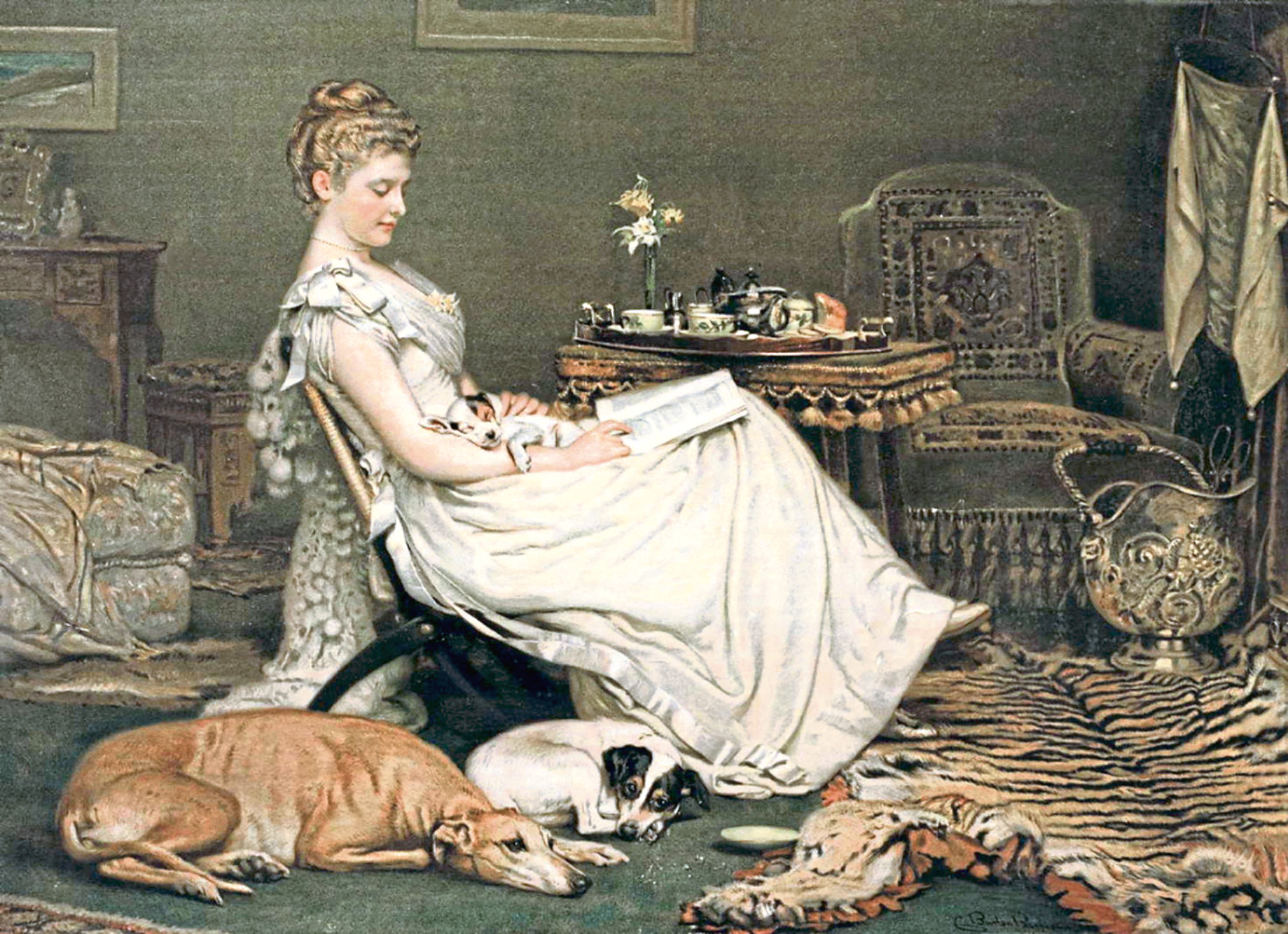

Sporting dogs were favoured by the upper classes even though few were used in the field. Middle class owners wanted fashionable breeds. Ladies favoured toy breeds. There were working-class fanciers, particularly for bulldogs, terriers and whippets.

How would dog breeds be developed at this time?

Breeders used selective breeding, keeping puppies with desired features and mating prize winners. They inbred to try to fix features. Cross-breeding helped acquire particular features.

Have practices changed in that regard?

Dog breeders still mainly use the same methods of selection, but are now informed by modern genetics and DNA analysis, which can help avoid dangerous inbreeding.

Illegal puppy farming is often in the news. Have we made positive strides in breeding since the Victorians or is there room for improvement?

Victorians complained that the nation of dog lovers was being threatened by “dog dealers” who were only interested in profit. You hear the same complaints today. There is always room for improvement. There are now many guidelines, regulations, licences and approved breeder schemes, but enforcement remains the big problem.

The Invention Of The Modern Dog, John Hopkins University Press, £29.50

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe