HE spent the First World War using his artistic skills to reveal enemy positions. He spent the Second World War using his genius for light and shade to hide the machinery of war from the enemy.

Now the remarkable life of artist and camouflage pioneer Joseph Gray is told in a new book by his great grand-daughter Mary Horlock.

And her step back into her family history helped explain not only her own artistic flair but also laid bare the sadness of her grandmother over the father she wished she’d known better.

Although born in South Shields, Joseph moved north and settled in Tayside, working as an illustrator for DC Thomson’s Dundee Courier.

He joined the local Black Watch Regiment at the start of the First World War in 1914 and was in the thick of the fighting for the next two years.

Joseph’s artistic skills were pressed into service as an observer, making drawings of German positions and targets.

“It must have been horrific and terrifying but I think drawing enabled him to escape it slightly,” said Mary.

“He was risking his life all the time, going out at dusk to make these sketches. Being an observer was really dangerous and you had to be wily to survive against the Germans who had better telescopic sights.

“But doing what he loved – he couldn’t not doodle, sketch, paint – made it much more bearable. And it also helped save his life.

“Because he was looking so intently at everything, the irregularities, the big guns and the snipers, I think he was able to last as long as he did.” His luck ran out when he was shot – although in his typically upbeat manner, he made light of it.

“He joked that it was his first lesson in camouflage,” said Mary.

“He said he was going over the top and his kilt flew up.

“He reckoned his very white backside made him an easy target.”

Joseph was treated for his bullet wound at the front, but he was subsequently invalided out with rheumatic fever.

He suffered badly with his lungs for years and was regularly hospitalised back in Dundee where he married and had a daughter, Maureen.

Some of his remarkable drawings from the trenches found their way into the Imperial War Museum, where they are still held.

He continued to work as an artist, but tough times during the Great Depression of the late 1920s and ‘30s made life very difficult for Joseph. And fears of another global conflict occupied his mind.

“It came to obsess him,” said Mary. “That generation had been through the ‘war to end all wars’, only to realise they were going to have to face it again.

“There was a lot of fear of the Luftwaffe delivering knockout blows that would totally disable our cities. He thought a lot about how to use lessons he’d learned about hiding things during the First World War and take them to a bigger scale.

“Some of the amazing camouflage drawings he did are also in the Imperial War Museum.”

He had an affair and left his wife Agnes, a decision that had a profound effect on his daughter Maureen

“He wasn’t always a great father,” says Mary. “There is no doubt that my grandmother missed his presence. There was a lot of his artwork in the house, but while she had his paintings she didn’t have him. That was something that had an effect for a lot of his life.

“I became aware that as she grew older, there was a lot about him that she didn’t know.

“They say that artists create their own opportunities and I think that for a lot of the time he kept reinventing himself.”

Although there was sadness and separation, Maureen still had cherished early memories. She died only recently at the age of 97. And a couple of years earlier, as she worked on the book, Mary revisited Tayside along with her grandmother.

“I took her to the Black Watch Museum in Perth and also to the Dundee Art Gallery which has his big First World War painting After Neuve Chapelle.

“It was amazing to be standing there with my grandmother and hear her recall how she used to bring her friends there after school and tell them that it was her dad that painted it.

“She was 95 at the time and it was lovely to think of her there as a 10-year-old.”

Art has always run in Mary’s family, with her mum also an artist.

With Joseph’s evocative paintings, often of Scottish scenes, on the walls of both her mum’s and gran’s houses, she’s sure that was part of the inspiration that led her, too, to follow an artistic career.

She worked at the Tate Gallery and became fascinated with the contrast between the modern artworks there and what were seen as Joseph’s more unfashionable, traditional paintings.

She wanted to find out more about the man she had heard about but had never met.

“When I started this part of what I wanted to do was help my grandmother understand him better. He’d gone off during the Blitz so she only knew bits of his life,” said Mary.

“I wasn’t setting out to portray him as a hero or show him as an undiscovered genius.

“But there are many remarkable people who served in the World Wars whom we don’t hear much about.

“I hope people learn more not just about Joe but also artists involved in this strange world of camouflage.

“He was more proud of his work with than anything else.

“I got hold of a lot of his personal letters and what shone through was despite everything he saw and lived through, he wasn’t scarred by it.

“There was a lot of sadness and he lost a lot of friends, but he always seemed to be incredibly upbeat. That was a lovely thing for me to take away.”

Joseph Gray’s Camouflage by Mary Horlock is published by Unbound

Master of disguise, even in one of his own oil paintings

The master of camouflage, Joseph Gray, even managed to hide himself in one of his first but most famous paintings.

Hooded and almost lost in the top right corner, he appears in “A Ration Party of the 4th Black Watch at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, 1915”.

It shows the soldiers running for cover after delivering rations to their comrade. As author Mary Horlock describes them “ragged spectres…half sunk in mud, half lost in shadow.”

As Gray did throughout his career as a artist, he portrayed the men who had been at the scene, asking them to model for his paintings (or if they had been killed in combat, using photographs).

Since he was there, he included himself, although typically, almost completely concealed.

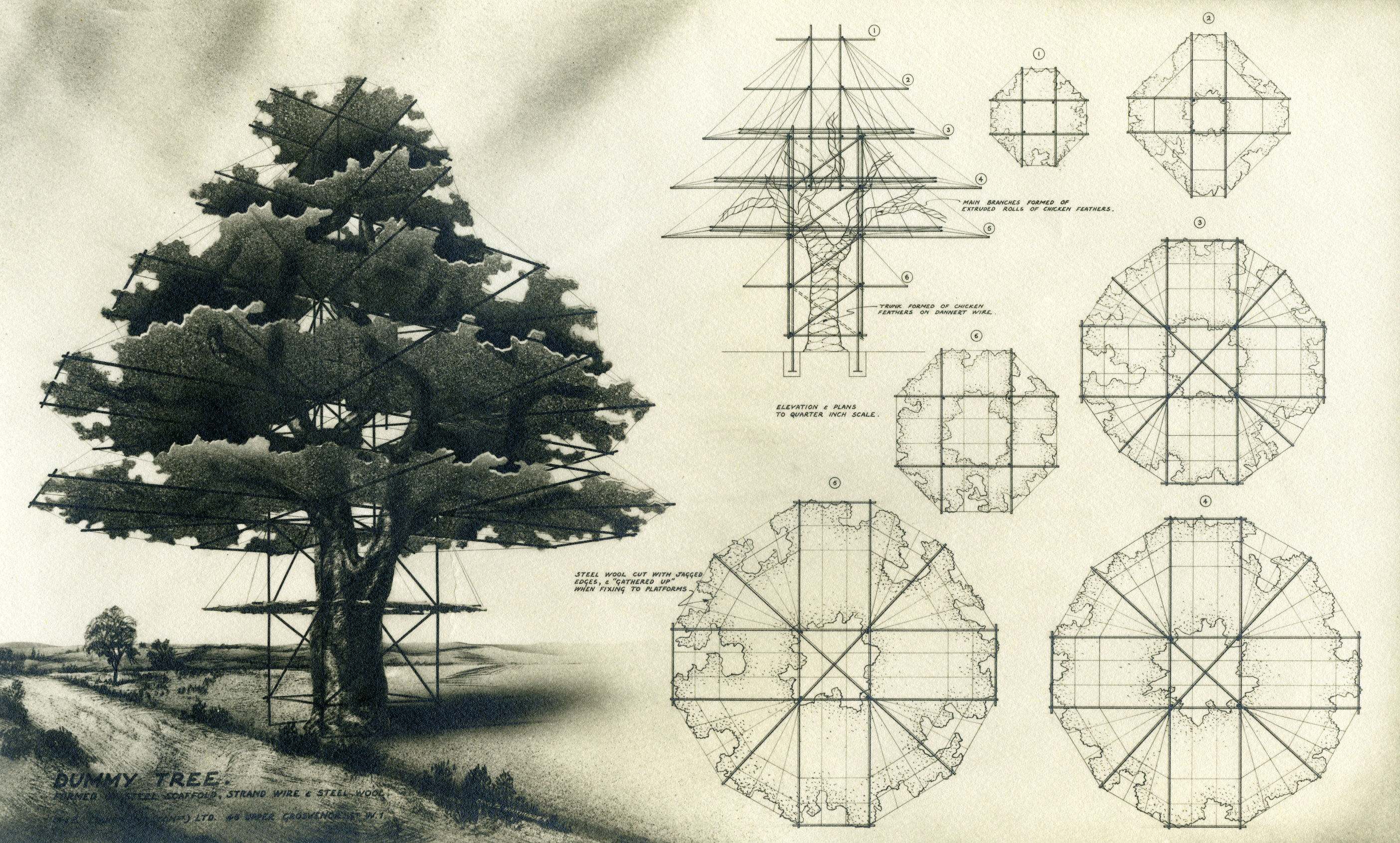

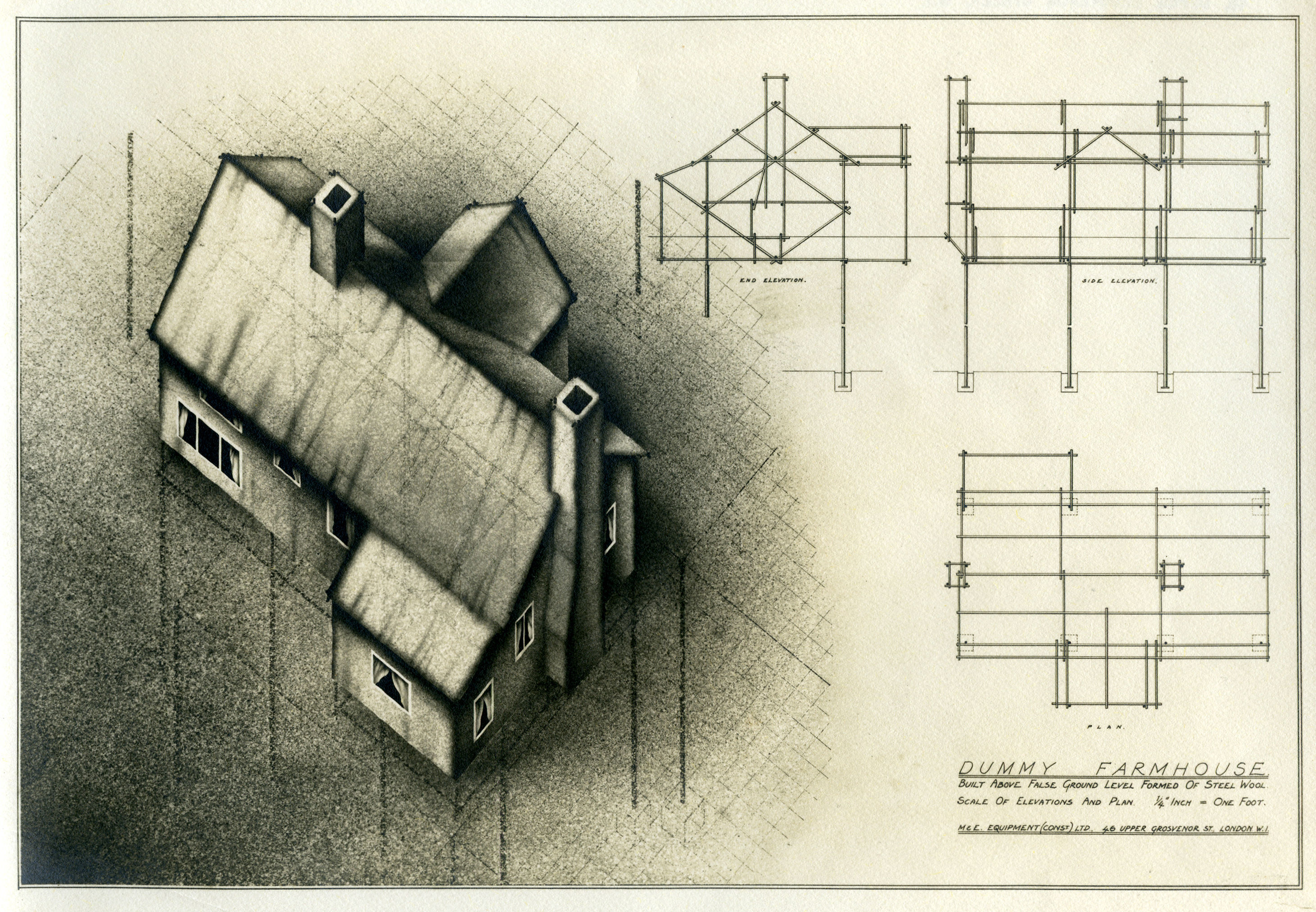

After realising his artistic skills, an awareness of colour, light and shade, made him an expert in camouflage. By 1936 he had completed a comprehensive report, Camouflage and Air Defence.

Such was his expertise, the War Office recruited him as a Major in the Royal Engineers and he was tasked with helping hide vital military targets.

Mary said: “He had seen large covers used on the battlefields and wanted to work out how to make them fit for big buildings and cities.

“He went round hardware stores trying all sorts of materials and hit on the idea of using steel wool.

“It could be stretched and painted and rolled out quickly to hide factories or gas works that the Luftwaffe would try to bomb.

“He even talked about giant covers that could be dropped from aircraft. While some of the ideas were very extreme, many were so practical.

“If something couldn’t be hidden completely, the thinking was to bamboozle the enemy as much as possible.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe