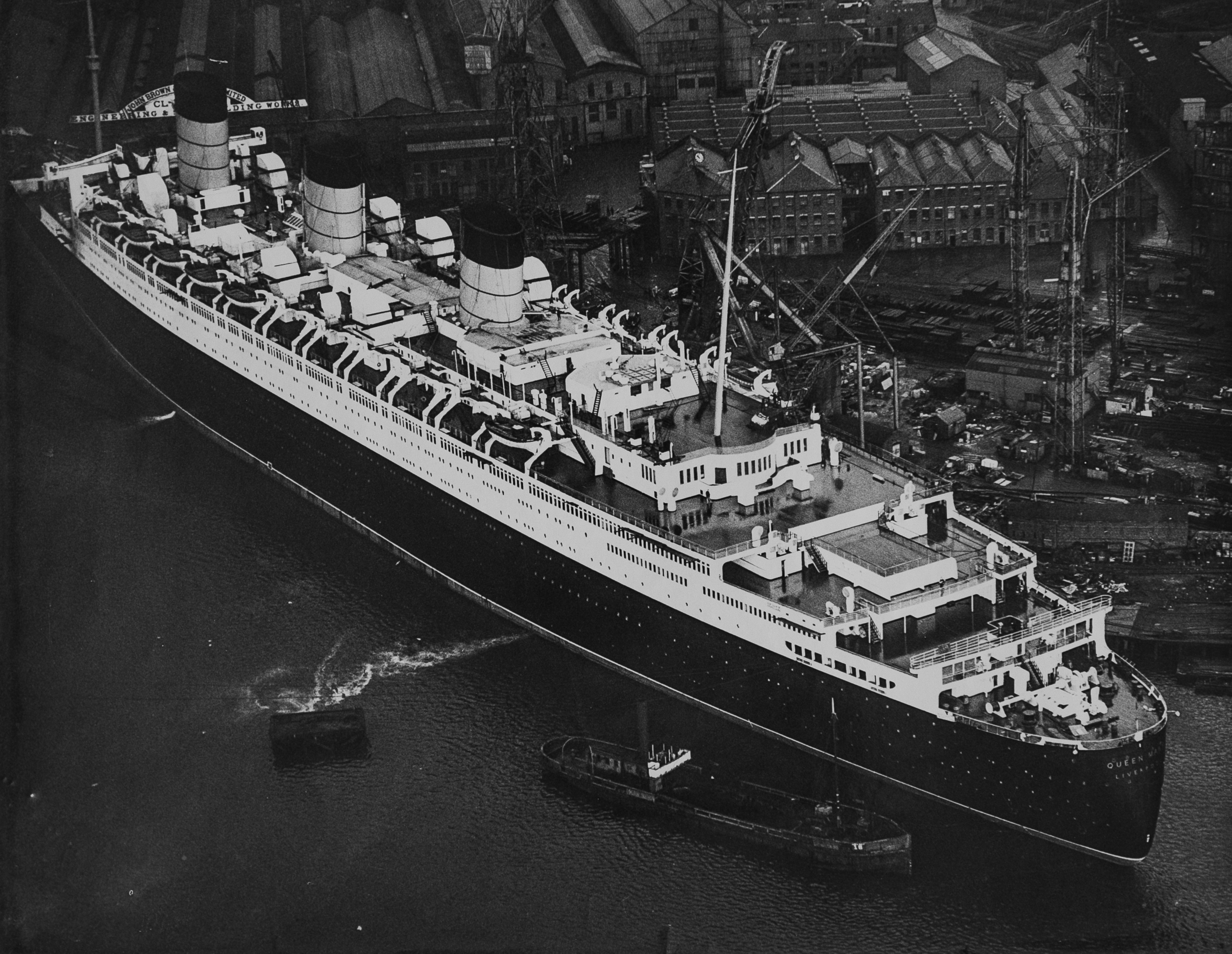

She was once the grandest ocean liner in the world, carrying A-list passengers such as Elizabeth Taylor, Clark Gable and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor across the Atlantic.

Now, on the eve of the 85th anniversary of the launch of the Queen Mary, The Sunday Post can share rare archive pictures and documents about the building of the vessel, which became the pride of the Clyde.

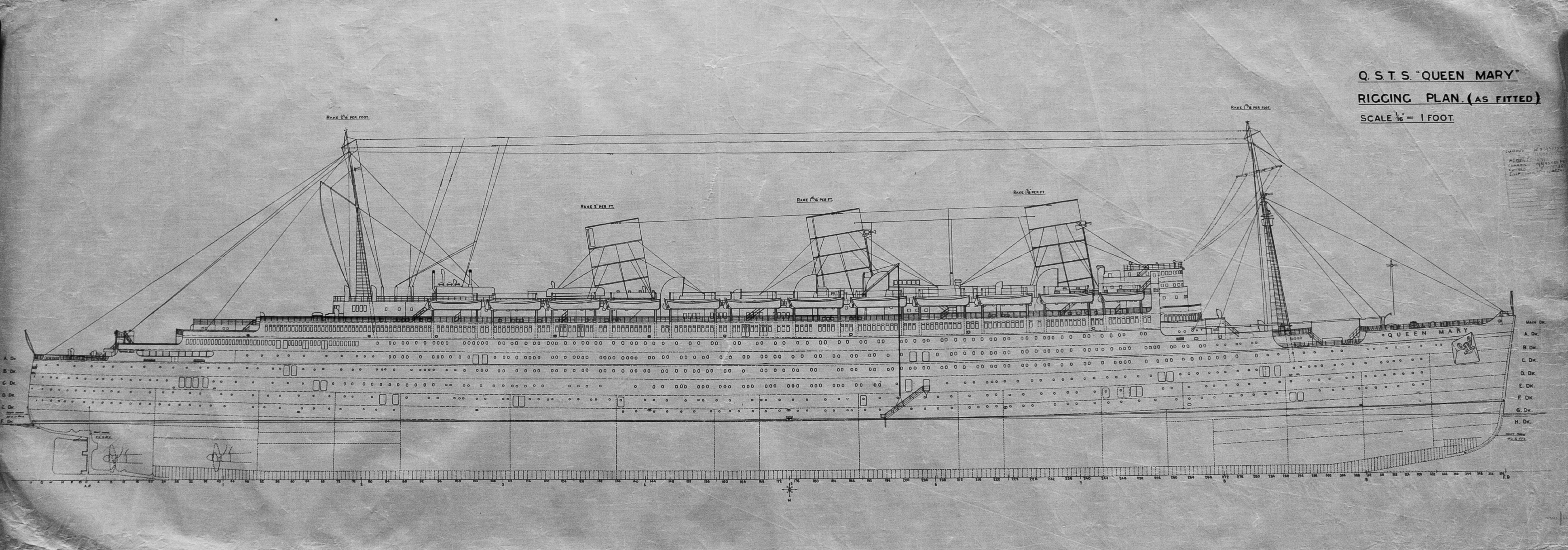

The University of Glasgow is the guardian of the plans for the ship, photographs of her launch and letters between John Brown’s shipyard and the Cunard-White Star shipping line during the three-and-a-half year construction at a cost of £3.5 million (£223m today) of what was then the world’s largest and fastest ocean-going liner.

“We have a unique record of the Queen Mary’s creation, from the design plans to detailed accounts that cover everything from wages down to the cost of cutlery and crockery, to photographs of the launch that show the immense scale of the ship,” said senior archivist Clare Paterson.

“John Brown became Upper Clyde Shipbuilders and when they went into liquidation, their records were saved by the university, the National Records of Scotland, Clydebank District Council and Glasgow City Council. As a result, we have a fabulous record of Scotland’s ship-building prestige.”

The collection’s jewels in the crown are the records donated by Stephen Piggott, director of John Brown in 1934, when the Queen Mary was launched into the River Clyde, parts of which had to be dredged and widened to cope with her bulk.

These records, carefully preserved in the university archives, include plans for the 80,000-ton liner, which was built to compete with German and French rivals on the Atlantic passage.

“The Clyde was a centre of excellence in shipbuilding, producing everything from tugs and puffers to battleships, to transatlantic liners that were as luxurious as floating hotels and took passengers across the world,” added Clare.

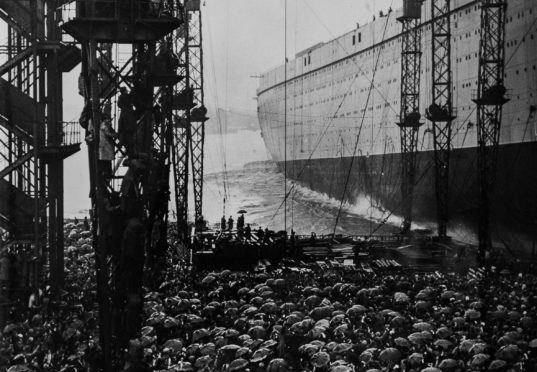

“Ship launches drew massive crowds as they were major events – but the Queen Mary was special.

“Nobody had made such a huge ocean-going liner before and she was a source of great pride for the shipyard owners, for the shipping line, for the designers, the workers who built her and the craftsmen and artists who fitted her out.”

Photographs from September 26, 1934 show huge crowds braving the rain to witness King George V and Queen Mary – for whom the ship was named – launch the enormous liner.

Legend has it that Cunard wanted to name the ship Victoria, but after asking the King for permission to name the ship “after Britain’s greatest Queen”, he replied that his wife would be delighted.

At the launch, the King said: “Today, we come to the happy task of sending on her way the stateliest ship now in being.”

The Prince of Wales also attended, in his capacity as Master of the Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets.

The archives hold brochures from the shipping line celebrating the Queen Mary and one account is of a visit to the yard shortly before the launch.

“You get your first sudden view of her monstrous bow, which rears into the sky. There she is – 1,018ft in length and 135ft high. You stand transfixed and gaping. If you could stand her up on one end alongside the Eiffel Tower in Paris she would top that structure by 18 feet.”

She was also the world’s fastest ship and in August 1936 captured the Blue Riband – awarded to the fastest ship to cross the Atlantic – with a top speed of 30 knots.

Her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York took place in May, 1936. She had a crew of 1,100 for 2,100 passengers, and supplies included 50,000lbs of meat, 50,000 eggs, 14,500 bottles of wine and 25,000 packets of cigarettes.

Such was the kudos of travelling on the Queen Mary, she carried Winston Churchill and John F Kennedy, and the stars of Hollywood’s golden age, including Judy Garland, Audrey Hepburn, Laurel and Hardy, Mary Pickford, Buster Keaton, Fred Astaire, Douglas Fairbanks Jr and David Niven, while Bob Hope was one of the entertainment acts.

During the Second World War, she was stripped and painted camouflage grey to carry troops. Her speed allowed her to avoid German U-boats and earned her the nickname, the Grey Ghost. She holds the record for the greatest number of people on one vessel at more than 16,000 and Churchill said her contribution shortened the war by a year.

On the same record-breaking trip, Queen Mary was hit by a rogue wave, thought to have been 28 metres high. She tipped 52 degrees and would have capsized if it had been three degrees more. The incident was the inspiration for Paul Gallico’s 1969 book, The Poseidon Adventure, about the capsizing of luxurious ocean liner, later adapted as a Hollywood film.

The Queen Mary returned to service after the war and dominated the transatlantic passenger trade until the arrival of the jet age. She was sold for £1.2m after completing her 1,000th and final trip, and in all carried more than two million passengers nearly four million miles. Since 1967 she has been moored at Long Beach, California as a hotel.

“The Queen Mary was a big statement for Britain and Cunard was determined to have the fastest, most prestigious liner. We are lucky to have these records, which have been preserved for the nation,” said Clare.

The blueprints

The sheer scale of the Queen Mary was proudly detailed in the plans held by the archive – 27 boilers occupying five rooms, seven turbo-generators with enough power to light up Aberdeen, while each funnel had a circumference of 100ft, wide enough to take three large trains side by side.

The Cunard records also describe how the immense size and weight of the Queen Mary required changes to the yard – the ground under her had to be strengthened with cross piles, steel plates and tons of concrete, while electric lifts were fitted to the sides of the vessel to carry workmen to the upper decks more than 100 feet above.

The liner was the last word in luxury. Nine double decker buses could fit into the first-class lounge, carpeted by Glasgow’s Templeton factory. The most prestigious artists of the day were commissioned to decorate her interior – a mural in the restaurant featuring a map of the Atlantic and a crystal model of the ship to track its progress was made by MacDonald Gill.

There were two swimming pools, beauty salons, libraries, nurseries, a music studio, a lecture hall, dog kennels and telephone connectivity to anywhere in the world. An acre of kitchens prepared 50,000 meals served during each crossing.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Andrew Cawley / DCT Media

© Andrew Cawley / DCT Media