Amid top-flight football’s extravagance and hyperbole, he stood out like a Lada in a Lamborghini showroom; a Joy Division fan at a Dire Straits gig; a healthy parrot in a post-match interview.

He took the Tube home from games, played The Fall on the team bus, and bought his clothes at Oxfam. Often Pat Nevin seemed, as the title of his newly-published autobiography suggests, an Accidental Footballer.

His pace, trickery and goals made him a favourite on the terraces of top clubs, including Chelsea and Everton, while his dress sense, taste in music and enthusiasm for opera and ballet made him a curio in the dressing rooms.

However, a new generation of socially-conscious, activist players have proved Nevin a pioneer. The former Scotland winger, now a respected commentator on the beautiful game, would always have preferred an anti-racism demo to post-match pints – he’s still never had one – but, today, many of the game’s superstars would probably join him.

Whether it’s campaigning for free school meals, awareness of mental health problems or taking a knee in support of Black Lives Matter, the stars of the game are increasingly keen to speak out, although Nevin, now 57, suspects it is easier for the likes of Marcus Rashford to take a stance today than it was when he was playing in the 1980s.

A former chair of the Professional Footballers’ Association, he helped launch campaigns against racism and homophobia in the game long before it became routine to see leading sports stars supporting causes like Black Lives Matter.

“If you look at it now, players are speaking up about racism but it’s because people are asking them about it now. Culture has moved on and changed a lot so it’s not as uncomfortable to speak about it,” he said.

“Back in the 80s it wasn’t like my team-mates were opposed to those opinions or to taking a position on issues away from football. They just weren’t particularly interested and it wasn’t important within the culture of the sport.

“These days there are more who are happy to do that. It may well be that, because footballers have an even higher profile, they’re being asked about it more. Plenty still just want to go and kick a ball and there’s nothing wrong with that either.

“I wasn’t being brave when I was speaking about a variety of issues, I was just being me and I hope footballers who are doing the same today are just being themselves.”

While he happily admits his enthusiasm for obscure indie bands and slim volumes by even more obscure Russian novelists could, at times, seem a little pretentious to team-mates with less esoteric tastes, Nevin was, then and now, being true to himself although he would now reach for a little PG Wodehouse before Dostoevsky.

His book, The Accidental Footballer – where every chapter is named after a different post-punk anthem – charts his life in football from growing up in Glasgow’s east end and forging a successful career at the very top level despite never not quite fitting in. The strength of character that would see him get up from innumerable scything tackles to go at defenders again and again, that allowed him to withstand a deliberately testing barracking from the great Jock Stein, meant being nicknamed Weirdo by his Chelsea team-mates was water off his Oxfam trenchcoat.

“They thought I was weird, but I thought some of them were weirder,” he said.

“Many of them drank far too much. They just didn’t have the same interests as me. They were heading off to the pub when I was going to the ballet or going to a gig. They also didn’t mix with ordinary people as much, and I think that’s even more the case these days.

“Footballers don’t mix with normal people. I think that’s stupid and just because you kick a ball and get paid more money doesn’t make you better than anybody else.

“Back when I played I thought that attitude was ridiculous. It’s a cracker of a

job, but it’s still just that. A job. Back when I played, I’d bring stuff into the dressing room and the rest of them would think I was weird and call it rubbish but 10 years later they’d all be listening to it.

“I understand why The Fall maybe gave them a headache. But George Michael gave me a headache.”

Other footballers might not have appreciated Pat’s post-punk musical tastes (he used to buy two copies of the NME because team-mates would invariably tear up the first one for laughs) but he didn’t let it bother him.

“I got it all the time. I just thought they were funny,” Nevin adds. “I used to get some amount of abuse at West Ham because I was into theatre and the arts and their fans were of the opinion that made me gay. It didn’t offend me because I don’t think gay is an offensive term and I wasn’t gay. They could sing that if they liked. I didn’t care.

“I’d just blow them a kiss. The biggest way to have a go at a bully is to laugh at them and be above them. Some players do find it hurtful but I was so comfortable in myself.

“That sounds awfully confident, doesn’t it? But I just knew myself pretty well and I was comfortable with who I was.

“It’s one of the messages I hope people take away from the book, to be yourself.

“I managed to go into an ultra-competitive world of football and it didn’t change me. I didn’t ever try to fit in and not be me. And if you don’t want me, I’ll go and try to do something else.

“And if you do try to fit in and not be yourself people can spot that. I’m no big brave guy and I managed it.”

Sound & vision

Pat Nevin reveals a few of his favourite things and why £400 bottle of wine is now to rich for his taste

What was your first gig?

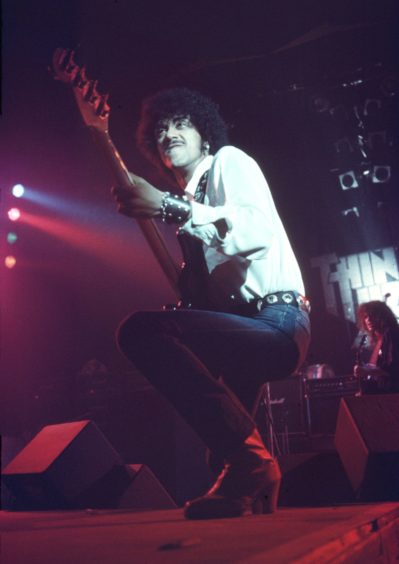

Thin Lizzy at the Glasgow Apollo in 1976, the Live And Dangerous Tour. This was before punk and I was completely mesmerised by Phil Lynott. It was brilliant rock and roll. Two or three years later I was going to see punk gigs and everything had changed. Thin Lizzy became dead unstylish. Now you say to people you saw Thin Lizzy and they say: “That’s cool!”

What song lyric speaks to you the most?

There’s a line from a song by The The called This Is The Day: “But the side of you they’ll never see/Is when you’re left alone with your memories/That hold your life together, like glue.” It’s a beautiful song and a great line but the reason that sticks with me is because it’s what I never wanted to be. I don’t want my memories to hold my life together, I want to be living in the moment. That line is almost like a warning.

What’s your favourite movie scene?

In the middle of my favourite film, Lost In Translation, Billy Murray’s character plays golf. He smacks a beautiful drive up the fairway on a lovely morning with Mount Fuji in the background. He picks up his ball and walks on. That scene was by somebody who must have crawled inside my head; as someone who’s travelled and spent a lot of time in hotels and foreign countries playing golf I recognise that. You play the perfect shot on the perfect day. And there’s nobody there.

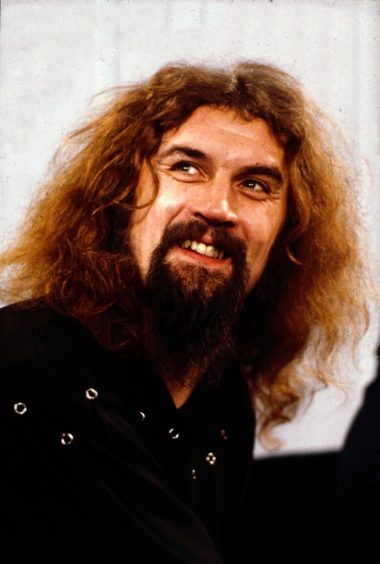

Who’s your ideal dinner party guest?

I’d love to sit down with Billy Connolly. Or my old mate Gerard Kelly, from City Lights, who’s sadly no longer with us. I used to love sitting down with Gerry, he was probably the funniest person I’ve met in my life. So one of those two, ideally both.

What’s your musical guilty pleasure?

I was chatting to Danny Baker about this recently. I’m known for being into my indie hipster and post-punk stuff and so is Danny. But we both agreed that early Genesis were brilliant. It’s not a guilty pleasure, they’re just great! Danny and I argued Genesis got rubbish when Peter Gabriel left, I say it was when Steve Hackett left.

Who alive or dead would you most like to go for a pint with?

I’m tempted to say Nelson Mandela but it would have to be Muhammad Ali. It would be fantastic to spend time with him on his own, away from the bombast. He probably wouldn’t want a pint, though. That’s OK as I don’t drink pints either.

What do you love to read?

I used to be very serious and very heavy when I was younger and I was into books about existentialism and all the rest of it. But these days it’s anything by PG Wodehouse. Anything with Jeeves and Wooster, the writing is incredible. Anyone who considers themselves a writer will read Wodehouse and recognise that he’s a genius.

What’s your favourite tipple?

I’ve never had a pint of beer in my life. I do drink wine and whisky like a fish, though. If you offered me a bottle of Penfolds Bin 707 Cabernet Sauvignon I’d be delighted as I haven’t had a sip of it in 15 years. I can’t afford it any more!

From the book

It didn’t feel odd to be sleeping on a bench after starring in Match of the Day

After a big game with Manchester City in May 1984, when he scored one and was named Man of the Match as Chelsea won 2-0, Pat Nevin did not join his team-mates on the coach south. Here, in an extract from The Accidental Footballer, he explains why.

This was Manchester in the early 80s and I had only one thought in mind: after a quick shower I was going straight to the Mecca of the northern music I liked, the Haçienda Club. I didn’t like nightclubs, generally but I loved Factory Records. They had Joy Division, New Order, A Certain Ratio as well as Vini Reilly and his band The Durutti Column on their label. This was before Madchester’s rave scene and I was aware this club didn’t yet have a great atmosphere – indeed, on that night, any atmosphere, as it was almost empty with maybe only a couple of dozen people in. I didn’t care, I wanted to see the design, the architecture, hear the music in that environment and simply experience the place almost as a pilgrimage.

It was an incredible place. It seemed huge, but that might have been because it was so empty. The music was already morphing well away from what Factory Records themselves were mostly producing. The dance tracks were being played, the audience just hadn’t turned up yet; the club was ready and waiting long before the Madchester scene was.

Tony Wilson, who was the impresario behind Factory Records, was already telling me over the thumping beats what an incredible place this was going to be and how it was going to change the whole idea of clubbing. I must admit it had the same effect as a used car salesman trying to sell me a 1960s Mercedes 280SL with 250,000 miles on the clock. It looks great but it just isn’t going to work, is it?

I loved the place and its Factory chic décor…The club might have looked finished but little did we know then that they had only just laid the musical and cultural foundations. Tony Wilson was right, but not for the first or indeed the last time he was there long before everyone else when it came to the cultural zeitgeist.

So instead of hopping on the team bus back to London I went to the “Hac” – I knew where my priorities lay! I had met both Vini Reilly and Tony Wilson and had a wonderful evening.

After leaving the club at 3am, I wandered down to Piccadilly station and slept on a bench on the platform before getting the early train back down to London. The thing is, even though the night before I had been starring in a match between Man City and Chelsea with a sell-out crowd and millions watching on telly, I didn’t find it at all odd that I was sleeping on a bench waiting for the milk train.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Colorsport/Shutterstock

© Colorsport/Shutterstock © Glyn Kirk/PA Wire/NMC Pool

© Glyn Kirk/PA Wire/NMC Pool © Colorsport/Shutterstock

© Colorsport/Shutterstock © Ian Dickson/Shutterstock

© Ian Dickson/Shutterstock © Shutterstock

© Shutterstock © ITV/Shutterstock

© ITV/Shutterstock © NurPhoto/PA Images

© NurPhoto/PA Images