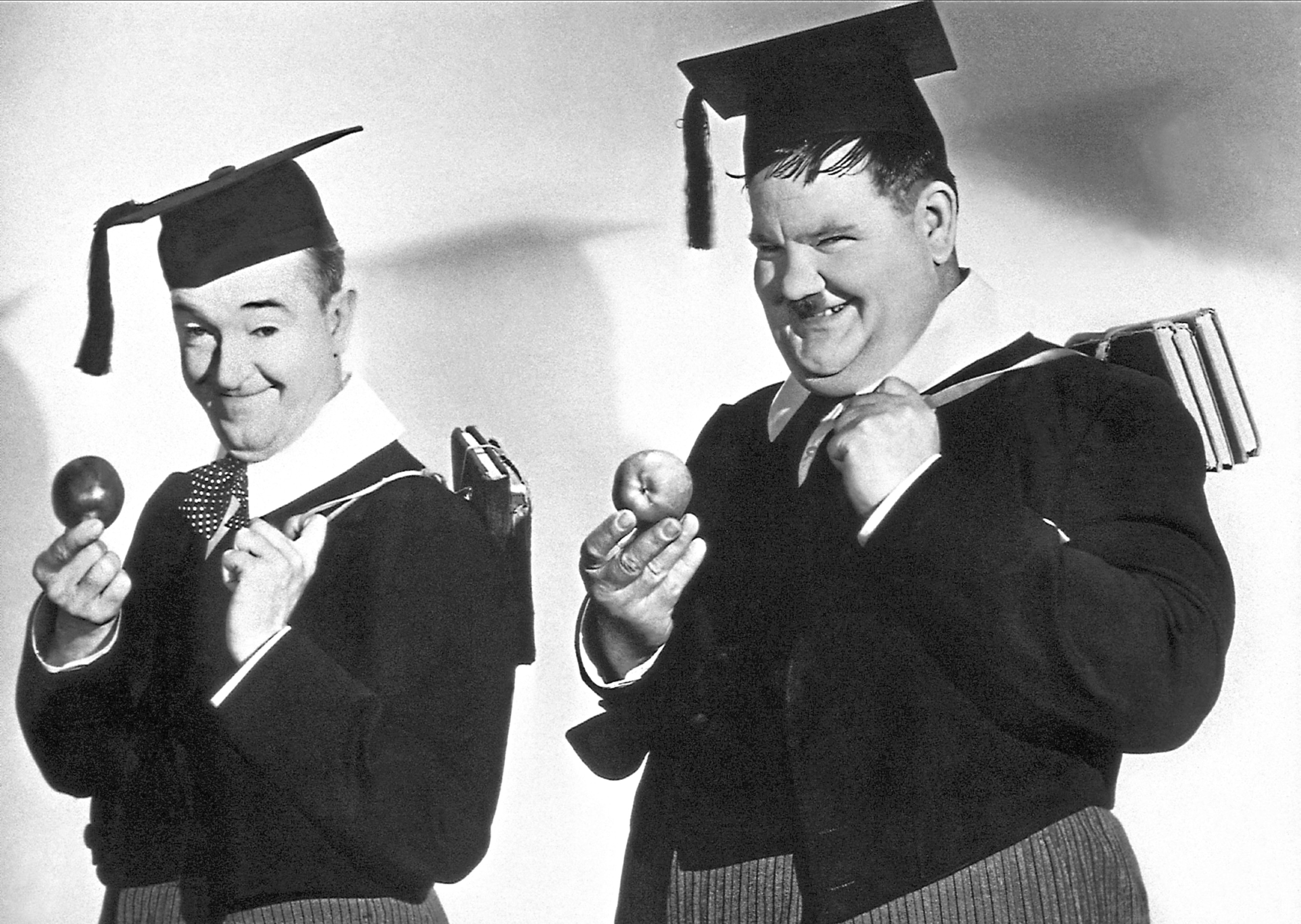

AS many people consider Stan and Ollie the funniest men ever, a new film about the comedy duo will be a huge surprise for various reasons.

For a start, it’s baffling to realise that there have been precious few, if any, movies or TV series made about Laurel and Hardy before.

It also comes as a bit of a shock to learn that this new movie will focus on one of the darker, sadder parts of their career, when their fame was on the wane, in 1953.

The film stars Steve Coogan as Stan Laurel and American star John C Reilly as Oliver Hardy, with filming having been done in Dudley, London, Bristol and Birmingham.

Most British viewers will have seen Coogan in something – Alan Partridge most famously – and Reilly is known as the voice of Wreck-It Ralph and for movies such as The Aviator.

In the new movie, we get to see a lot of Stan and Ollie’s old animosities come to the surface as they suffer one disappointing gig after another.

Laurel and Hardy did have fall-outs, but it also shows how much they relied on one another, with the whole world knowing them as a duo.

Considering, however, thousands had greeted them at Southampton Docks in 1932, but couldn’t even be bothered buying theatre tickets in ’53, it’s a sad tale, too.

To understand why their stars waned, you have to appreciate just how they reached the top and how huge they were.

For one thing, they both had pretty well-established film careers of their own before getting together, with more than 300 appearances combined.

So the slim Englishman and the rotund American had all the know-how they required, but just needed the perfect foil, someone to play off.

Boy, did they find it.

As Laurel and Hardy, they would go on to appear in 107 movies, including 32 silent shorts, 40 shorts with sound and 23 full-length feature films.

By the time they produced the first of those “proper” films, Ollie was already 35, his partner 37. So the duo was no overnight success story.

Hal Roach, a giant of US film and TV as a producer, director and writer, was working with Hardy when he spotted Laurel in vaudeville.

Although he felt they could work well together, he had a big problem with Laurel’s eyes.

Apparently, his very light blue peepers caused problems with the film technology of the time, because blue like his came out as white.

You can see this issue in their first film together, the 1921 silent The Lucky Dog. They made up for it, to an extent, by applying plenty of make-up on Stan.

When film finally caught up and such problems could be forgotten, what Roach loved was that both his new stars were funny men.

Normally a duo like this would have a straight man with a poker face and a funny man with a daft face, but Roach enthused: “You could always cut to a close-up of either one, and their reaction was good for another laugh.”

As the world would appreciate, this would often involve Laurel looking sad or weepy, and Hardy looking furious.

Their chemistry was fantastic, but it would be a few years before they made another film together and both men had pretty much forgotten their debut.

That all changed with the 1926 movie 42 Minutes From Hollywood – they never appeared in a scene together, and Stan’s only scene saw him in bed.

A year on, the first official Laurel and Hardy film, Putting Pants On Philip launched them to stardom, even if it did last less than 20 minutes and was silent.

Stan, who had spent plenty time in the real Scotland, appeared in full Highland dress.

There was no shortage of slapstick-style humour and gags based around the kilt and Ollie’s attempts to get his little pal into normal trousers.

It was with The Second Hundred Years, also from 1927, where they played two prison convicts, that outsiders began to say they made a great team.

Leo McCarey, the man who gave us Marx Brothers classic Duck Soup, suggested Laurel and Hardy ought to be a pair permanently.

McCarey also suggested they try less hard and slow the pace of their scenes. It would make them the No 1 comedy duo for three decades.

They’d both bring their personalities and ideas to their work, but there is no doubt Stan was the one who went away and racked his brains to come up with fresh gags.

Even when Roach had four or more writers, Stan would often rewrite huge chunks of movies and even, at times, the entire script.

He was so good that his partner was happy to leave him to it.

Ollie pointed out that if Stan wanted to bring more pressure on himself, he was welcome to it.

“Just doing the gags was hard enough work, especially if you have taken as many falls and been dumped in as many mudholes as I have!” he said.

Of course, as each film gained bigger viewing figures, the studios were smart enough to acknowledge this pair knew what they were doing.

It wasn’t often, if ever, that Stan would disagree with a director and not be listened to. They knew he was on the ball.

The close of the 20s, start of the 30s, was a dreadful time for many an actor and filmmaker, as the shift from Silent to Sound ended many a career.

Laurel and Hardy showed their genius at this point, continuing to rely on their magnificent visual gags.

Pardon Us, their first full-length movie, was so popular, in fact, they had to do voices for Spanish and French versions.

Italian and German versions were then done, too, though some of these are hard to find now, so worth a fortune.

Many Laurel & Hardy fans will be part of The Sons Of The Desert.

This was the title of their 1933 masterpiece, and also the worldwide organisation that devotes much time, energy and expense to keeping their heroes’ legacy alive.

Many members wear a fez, as worn by Stan and Ollie, and the film came out in the UK as Fraternally Yours.

The story of two members of a fraternal lodge who draw very different reactions from their wives in their quest to attend a meeting in Chicago, it ends with Stan being lovingly pampered by his missus, while Ollie has crockery and pots and pans thrown at him by his.

It has been deemed one of the most culturally significant movies ever, but we love the fact it still makes you laugh out loud, even for the zillionth time.

Stan was back in tartan for Bonnie Scotland, the 1935 film in which he played Stanley McLaurel, travelling to Scotland as a stowaway to collect his grandfather’s fortune.

Sadly, their days with Hal Roach were coming to an end, and 1940’s A Chump At Oxford proved to be their last but one with the man who had found them.

At the peak of their powers, they could fill cinemas and have queues right round the block, and toddlers to grannies could enjoy their comedy.

After their moves to other studios in the 40s, however, they found they suddenly had less power over scripts.

They embarked on stage tours of theatres, in Britain and Ireland, but the real glory days had gone.

It’s strange, to see the first major film about them focusing on that part – in the decades that had gone before, nobody could hold a candle to Laurel and Hardy.

Stan & Ollie is in cinemas from today

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe