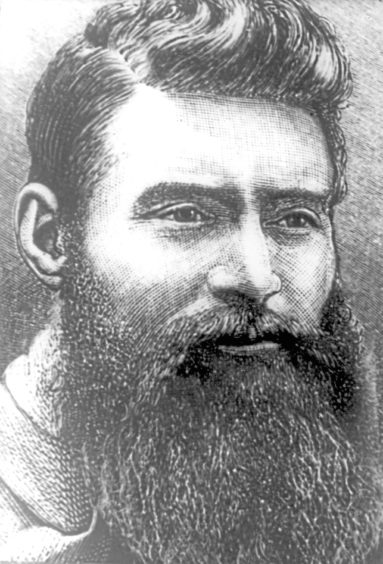

Folk hero, freedom fighter or cold-hearted killer? The legend of Ned Kelly has been the subject of heated debate since his death in 1880, aged just 25.

Now a new film about Australia’s notorious outlaw, The True History Of The Kelly Gang, based on an award-winning novel by Peter Carey, gives Ned’s own account of his story, based on a letter he wrote the year before he was hanged.

In this 8,000-word document, Kelly attempted to justify his crimes, which included violent robbery and murder, claiming unfair treatment of himself and his family by the authorities.

It tells of a handsome young bushranger – the Australian equivalent of cowboy – forced into a life of crime by police brutality and unwarranted victimisation.

In the 120 years since his death Ned Kelly has become a near-mythical figure in the mould of Butch Cassidy, Che Guevara or Bonnie and Clyde.

Ned grew up in the bosom of an already rebellious Irish immigrant family in the town of Beveridge, near Melbourne – his Irish immigrant father had been deported from Ireland some years earlier for stealing a pig — who regularly clashed with the rough outback justice dispensed by the local colonial police, often Irish immigrants themselves.

As a boy Ned seems to have been resourceful, loyal and brave. He rescued a school friend from drowning and was rewarded with a peacock green sash in gratitude by the boy’s parents.

He later wrote that “it were a mighty moment in my early life”.

In his teens he came under the influence of a renegade bushranger, Harry Power (played by Russell Crowe in the new film) who had little regard for colonial authority. Legend has it that Ned’s mother Ellen sold him to Power to toughen him up. The actress Essie Davis, who plays Ellen in the new film, disagrees.

She says: “I don’t think she would see it as selling him. She is giving him an apprenticeship in survival in life with someone who is clearly self-sufficient and quite wealthy, on the right side of the law, because as far as she’s concerned the law are all criminals.”

Harry Power, also deported from Ireland for theft, was a charismatic character who clearly had a strong – and undoubtedly bad – influence on the young Kelly.

He was renowned for his sense of humour, and once stole the guns, clothes and boots of three young bushrangers, leaving them to find their way home naked.

Each encounter with the law pushed Ned further and further into the mire of criminality until, in 1877, he shot and injured a policeman trying to arrest his younger brother Dan for horse theft.

The brothers fled into the bush, where two other men – Joe Byrne and Steve Hart – joined them to form the Kelly Gang.

Even at the time, some regarded Kelly’s descent into lawlessness as heroic – a blow for the underclass of the outback against the oppressive forces of law and order.

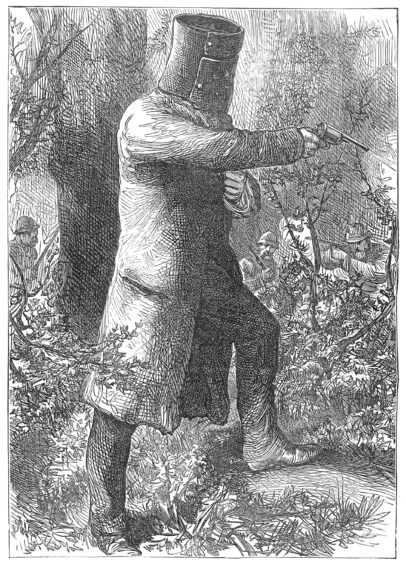

In 1879, by now wanted for bank robbery, horse theft and murder, Ned and his gang created their own self-styled suits of armour (each weighing around 90 pounds) from the thick metal parts of a farmer’s plough, which allowed them to walk away unharmed from close gunfire.

These Dalek-like body suits also had the effect of making them look much larger and a lot more intimidating although they were known for their good treatment of civilians and hostages.

The remnants of the metal suits are now on display in the Victoria State Library, along with a digital reconstruction of how the armour was put together.

A massive manhunt began after the gang shot dead three policeman. After holding up a railway station in the town of Glenrowan in June 1880, they herded a group of townsfolk into the Glenrowan Hotel and held them hostage, in the hope of making their getaway.

In the ensuing shoot-out three members of the gang were killed but Kelly himself escaped, reappearing in his “armour” the following morning at sunrise to try to rescue the others.

This time the police disarmed him by aiming shots at his unprotected legs.

On November 11 1880, Ned was hanged at the Old Melbourne Gaol and buried in a mass grave. His last words were reported to have been: “Such is life.”

A plaster death mask of Kelly – this was common practice in the 19th Century – was put on display after the hanging. Nearly a century later, a skull purportedly belonging to Kelly was reported stolen from Old Melbourne Gaol.

Like the anti-heroes of the Wild West in the US at that time, Ned Kelly has featured prominently in popular Australian culture ever since.

The first film on the subject, The Story Of The Kelly Gang, was released in 1906. It was the world’s first dramatic feature-length movie.

Former Australian football star Bob Chitty played the young outlaw in The Glenrowan Affair in 1951, and Rolling Stones frontman Mick Jagger donned the metal armour in Tony Richardson’s Ned Kelly 20 years later.

The critics mocked Jagger’s performance mercilessly, saying he looked more Amish than Irish-Australian. A review in the Radio Times’ Guide To Films declares his performance is “so similar to his rock star stage image that you half expect him to start shrieking”.

The late Heath Ledger fared better in the beautifully shot 2003 film Ned Kelly, based on Robert Drewe’s 1991 novel Our Sunshine, with a supporting cast that included Orlando Bloom, Geoffrey Rush and Naomi Watts.

Reviewing it for The Observer at the time, Philip French concluded: “Oliver Stapleton’s atmospheric photography appears to be based on 19th Century Australian painters, most significantly Tom Roberts and his school.

“The shoot-outs are well staged and the appearance of Ned and his comrades in their homemade steel armour makes for a sight both fearsome and comic.”

British-born composer Luke Styles successfully premiered his opera about Ned Kelly at the Perth Festival last year – The Guardian called it “a solid, gripping production, mostly because the music and performances are terrific”.

There were also several plays written about Kelly after he died, and musicians as diverse as country music legend Johnny Cash and Aussie rockers Midnight Oil have serenaded his memory.

In the 1940s, the great Australian artist Sidney Nolan (1917-1992) made a striking series of paintings inspired by Kelly’s armour, which are on permanent display in the National Gallery of Australia. They follow the trajectory of the Kelly story and are supposed to represent Nolan’s ideas about injustice, love and betrayal. It also enabled Nolan to find new ways to paint the Australian outback.

In Victoria, “Kelly tourism” sustains towns in and around Glenrowan, where the authorities finally tracked him down. The rural districts of NE Victoria are commonly referred to as Kelly Country.

In short, Ned Kelly has been well and truly commodified, with T-shirts, tattoos, and beers branded in his name.

The new film, starring 1917’s George MacKay as the young outlaw, was described recently by the Sunday Times as “a dizzying drama of scorched landscapes, mud, blood, madness and sensuality”.

The world loves a bad boy, it seems, and if he fervently believes he has right on his side, they love him all the more.

The True Story Of The Kelly Gang is on general release.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Bentley Archive/Popperfoto via Getty Images

© Bentley Archive/Popperfoto via Getty Images © Granger/Shutterstock

© Granger/Shutterstock