AS Angus Roxburgh shook hands with Vladimir Putin, he felt the Russian president’s steely eyes boring into him with a knowing, familiar look.

The Scot wondered if the controversial leader was thinking the same thing he was – that their paths might have crossed years before, when a KGB agent bearing a serious likeness to Putin burst into a hotel room in Leningrad and tried to drag Angus away. That he was prevented by the Stonehaven man’s then-wife, who sat on Angus’s lap and refused to budge for “Putin” and his heavies, only makes the story even more incredible.

Yet it’s just one of the fantastic tales that Angus can call upon from a 40-year career spent predominantly in Russia – working as a translator, as the BBC’s Moscow correspondent and as a media adviser to Putin’s Kremlin.

His new book Moscow Calling, published by Birlinn, recounts his years writing the first draft of history behind the Iron Curtain.

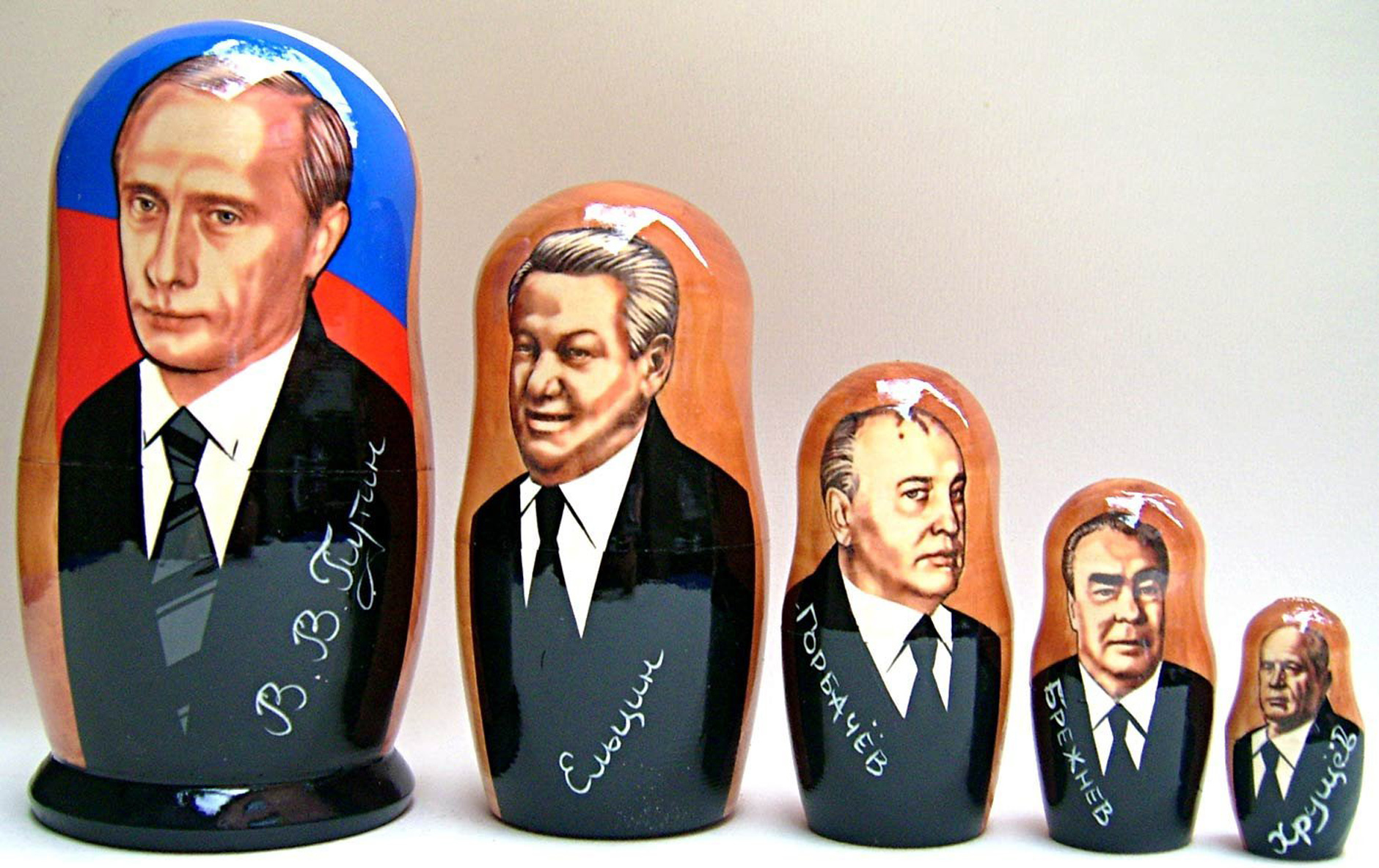

Along the way he met four successive Russian presidents, was unwittingly wooed by the KGB, faced accusations of being a British spy, was expelled from Russia for a drunken comment he made in a Glasgow pub years earlier and was jinxed by Siberian shamans. Twice. With a CV like that it’s hard to know where to start with Angus, but the best way to explain how he ended up in Moscow is to go back to his childhood.

“Growing up in Stonehaven, I had a Pye wireless set which I listened to for hours on end,” recalled Angus. “It could pick up stations from all over the world.”

The strongest signal came from the USSR stations, “probably so they could clearly emit their propaganda”, he laughed, and he was soon obsessed by the sound of the Russian language.

The library at his school, Mackie Academy, had four Russian textbooks and he taught himself in his spare time, passing his O level.

Then, in 1974, he visited the communist country for the first time and immediately fell in love with the place. “I realised there was a lot of fun to be had in Russia and it wasn’t just this grim place it had been portrayed as in the west,” said Angus.

Alongside his ex-wife, Neilian, Angus first lived in Moscow in 1978. He was employed as a translator for a publishing company, settling into the Russian way of life with all its peculiarities.

But it was on a return trip in 1982 that he personally encountered the heavy-handedness of the KGB – and a possible early meeting with Putin.

“We were there as interpreters to the touring Glasgow Youth Band. One evening in Leningrad we had dinner in the home of the musical director from the hosting Soviet song-and-dance troupe.

“I remarked how great it was that we could get on together and said it was a shame Mrs Thatcher and Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet leader at the time, couldn’t do the same. I said they should forget their ideologies and do so.

“They drove us back to our hotel, where we continued our chat, but at two in the morning the door burst open and three KGB agents wearing leather jackets and stinking of drink stormed in and demanded I go with them. Clearly the bugs in the flat, or the hotel, had been working. One of the thugs tried to drag me away, but Neilian sat on my knees to prevent the arrest.”

That brave action, as well as the Russians in the room flashing their red ID cards, persuaded the KGB to leave Angus alone.

Years later, as Putin climbed the political ranks, Angus felt a strange sense of familiarity which he traced back to the night the KGB came calling.

He said: “It was much later when I realised the man who tried to arrest me bore a close resemblance to Putin. He had the same mouth, hair and cold eyes. His job was closely monitoring the movements of western visitors. Visitors exactly like me.”

So it seems hard to believe that from 2006 to 2009, while working for a Brussels-based PR company, Angus was a media consultant to Putin’s administration – not that much of what he said was taken on board.

Long before then, though, and after he was a translator, Angus became a journalist and was The Sunday Times’ Moscow correspondent.

Life was good and, as the country slowly emerged from communism, Angus forgot about the KGB. But they were there – and they wanted to recruit him.

“I didn’t realise,” Angus said. “But looking back at some of the friends I acquired, who turned out to be KGB agents, maybe I was naïve.

“One of them later defected to America and stated that one of his assigned tasks was to see if I was recruitable. I didn’t take the bait.”

These days, 63-year-old Angus is based in Edinburgh but Russia remains close to his heart.

His three kids – Ewan, Duncan and Katie – spent much of their childhoods there and Angus has a genuine love for the place.

He’ll continue to visit and his most recent trip, in June, was just like old times – KGB raid and all!

“I was translator for Political Tours, where holidaymakers meet with politicians, experts and journalists.

“We were in Nizhny Novgorod for a meeting with one of Putin’s party when five heavies came through the door, demanding our passports and taking us to the police station.

“They held the party for four hours and me for seven. The British Embassy arranged a lawyer and I was told I’d be freed if I paid a small fine and confessed to breaking the terms of my visa, which I hadn’t, but I signed it anyway.”

Angus’s many adventures in Russia make for a unique, fascinating and engaging new book – and there will be more stories to tell.

Angus added: “I hope its current bad atmosphere is temporary, but it won’t lift until Putin’s gone – and he’ll be around for a while yet.”

Moscow Calling: Memoirs Of A Foreign Correspondent will be published by Birlinn on September 14.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe