Mark Bonnar’s childhood was a little different.

As a toddler in a Dundee tenement flat, his dad Stan, then an art student, strung aluminium balls on nylon from the ceiling in an attempt to perfect his degree-show statement piece on the beauty of outer space.

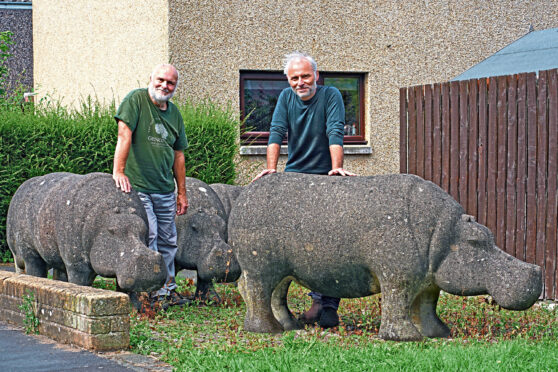

Later, as a wee boy, Mark played with playgroup pals on giant concrete hippos and mushrooms on pathways around Glenrothes.

These playful and surreal sculptures had been made by his dad, for the growing New Town in the early 1970s.

After the family moved to Stonehouse in Lanarkshire, the actor – well known for TV dramas such as Catastrophe, Line Of Duty and, most recently, Guilt and Shetland – helped his dad create artworks in the woods around the dilapidated farmhouse where they lived.

An old photograph shows six-year-old Mark, in Donald Duck T-shirt, shorts and wellies, clutching a pole and standing in the middle of what looks like a carefully dug shallow trench leading to a mound of earth. In front of him sits a small boulder, above which is suspended a model Messerschmitt jet aircraft.

Stan, by then working as town artist for East Kilbride and Stonehouse Development Corporation, made Messerschmitt Cut in his spare time.

The work, a comment on the need for a fairer society after the horrors of the Second World War, was, as Stan says now, “made for myself and for people who lived near these places, to stumble upon”.

Earlier this year, during a road trip with his dad around Scotland’s five New Towns for a BBC Scotland documentary called Meet You At The Hippos, Mark and Stan went in search of Messerschmitt Cut.

“We went looking after filming had ended for the day in Stonehouse,” says Mark, who was born in Dundee in 1968.

“Dad and I searched and searched, but the ground around where he made the work was completely overgrown so sadly there was no trace of it.

“It was so strange yet so familiar to be back in and around Stonehouse. I went there as a five-year-old. At first we lived in a farmhouse and then moved into Murray Drive in the village. We left when I was 11 to move to Edinburgh, so I spent my formative years there and the geography of the place was so familiar.

“I still keep in touch with my best friend, Stewy, and we met his brother the day we filmed there. It was a very special day for both me and dad, meeting and talking to people in Stonehouse who greeted us so warmly.”

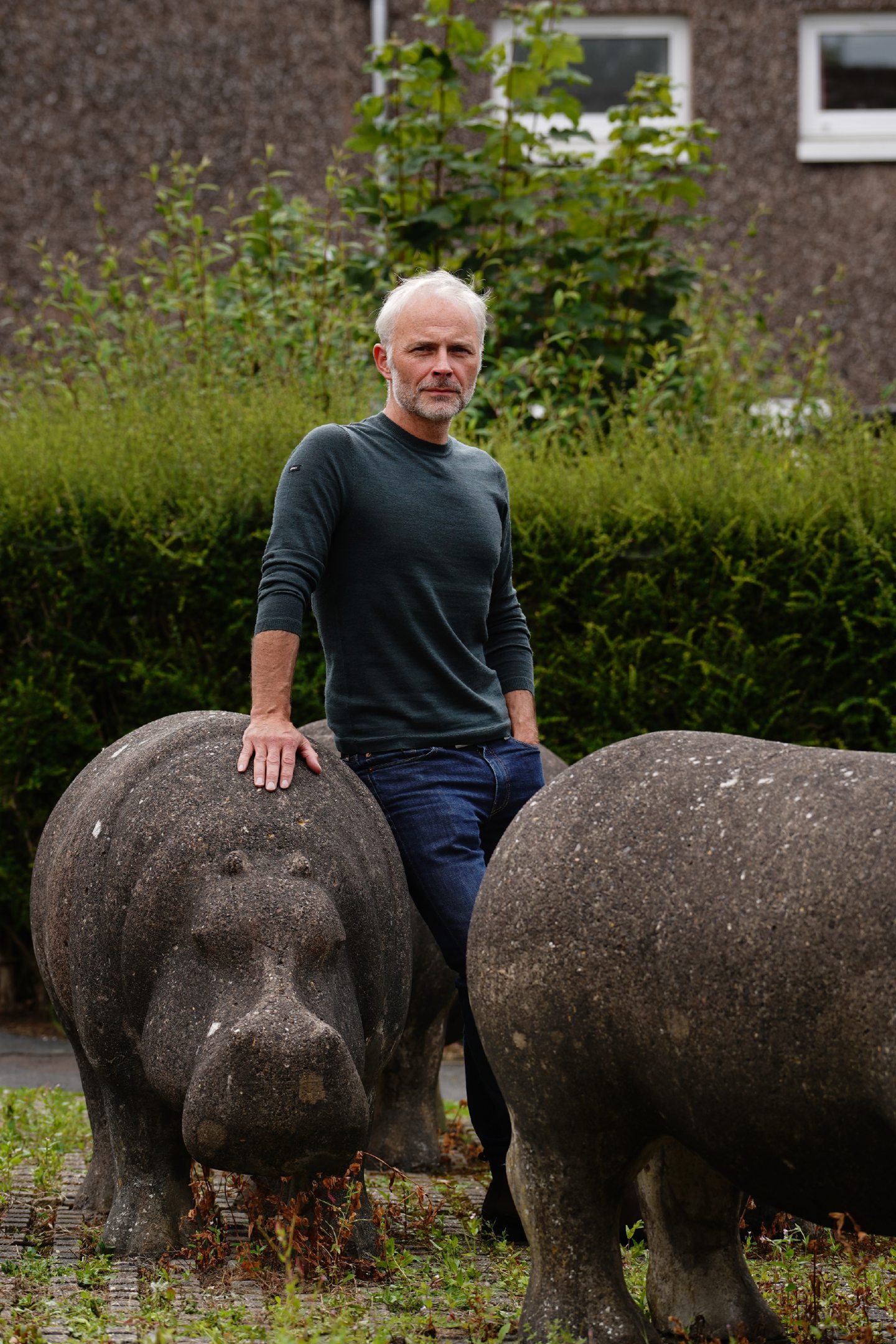

Meet You At The Hippos, which airs on St Andrew’s Day, tells the story of Scotland’s New Town art and the artists who made, it through the eyes of Mark in his first presenting role.

In this quirky, funny and informative hour-long concrete art odyssey around Scotland, the actor switches between a check-jacketed know-it-all documentary presenter persona (“a bit Alan Whicker-like”, he jokes), and his true “what do I know about presenting an art documentary?” self.

The Bonnars’ day out in Stonehouse was, says Mark, a highlight of a two-week filming period, with the two men travelling around Scotland from Glenrothes in the east, to Livingston, Cumbernauld, East Kilbride and Stonehouse and Irvine on the west coast.

The title of the documentary comes from Glenrothes’ famous concrete hippos, which Stan designed in 1974 and are dotted around the Fife town.

Mark explains: “The Glenrothes hippos have become symbolic of the town and ‘meet you at the hippos’ is something people say to each other when they arrange to meet up.

“The story of Scotland’s New Town art is one that has never been told before on screen and for me it was my first foray into presenting, which was an eye-opening experience.

“Making a documentary moves at breakneck speed compared to making a drama like Guilt. As a presenter, you are listening all day and ‘on’ all day whereas in a drama you’re ‘on’ in bursts – and you have a script!”

It was also a rare opportunity for the father and son to spend quality time together – and, for Mark, a chance to reflect on the part art has played in shaping his own life.

He says: “Your parents are your parents growing up and you just accept things the way they are, but growing up with an artist for a dad – and a creative mum too – definitely had an effect on my eventual choice of career. It creates an acceptance that being creative is the norm.

“As a kid, I would help dad with his art and art was always there. I was very into things like fly tying as a kid and painting Dungeons And Dragons figures. I found both really meditative.

“Now I live in London with my young family while my mum, Rosi, and dad are still in Scotland, in Berwickshire. And, with various lockdowns, we haven’t seen each other as much as we’d like.

“Making this documentary meant we spent a lot of time in the car driving to and from one New Town to another and then home to my parents’ house at night time, which we are already both looking back on with great affection.

“We’d talk about the day ahead and ideas and philosophies around art on the way to the New Towns and at night we’d do a wee dissection of the day.

“It was an immensely rewarding experience and that precious time we spent together was the bonus of filming the show. I love art and being able to communicate that in an accessible way through this programme – with my dad – has been a joy.”

For Stan it was an equally bonding experience. He says: “Mark’s mum Rosi and I are incredibly proud of both our sons, Mark and Vincent. Both are creative. Vincent lives in Edinburgh and is a professional musician.

“We’ve watched Mark’s career as an actor develop over the years. We sit there watching Guilt, which we both love, just smiling at each other. My respect for what he does as a professional has grown over the course of making this documentary.”

As well as offering the chance to spend time with one another, it was a learning curve for both men in terms of finding out about themselves and the art made in the five New Towns. After initial reservations – “that’s just me being me after years of being a struggling artist” – Stan, 73, admits the experience has been one of the most rewarding of his life.

He adds: “When the idea was first brought up last year, Mark said,‘look dad, this is a great opportunity’ and that got me into it.

“As the preparations were made through lockdowns, I began to get really excited. My whole philosophy on art is based around the environment and it started to fall into place that we were telling the story of the artworks around the New Towns and how people interacted with them.

“Mark was born when I was just 20. In his early years, I was an art student in Dundee and then we moved to Glenrothes, where I was assistant to David Harding, the New Town artist.

“Our lives revolved around young children in Glenrothes and then Stonehouse, so it was no surprise the artworks I made back then, such as concrete hippos, mushrooms and elephants, are so playful.”

The story of Stonehouse, the New Town that never was, is central to the Bonnar family’s own story.

Today, anyone visiting the village, which consists of two streets constructed in the early 1970s, might be confused about why there are large concrete elephants, made by one Stan Bonnar, on Murray Drive, the first of the New Town streets.

Stan made a herd of elephants, which found their way to Murray Drive – and also to the Greenhills area of nearby East Kilbride.

Stonehouse was originally planned as Scotland’s sixth New Town, housing 35,000 people, rising to a potential 70,000 inhabitants but, in May 1976, two days after the first families moved into Murray Drive, it was announced in Westminster that further development would not proceed.

The Bonnars lived on Murray Drive until the late 1970s. In the film, Mark is seen chatting to Stonehouse resident and graphic designer Rae McCulloch, who remembers playing on and around the elephants as a child.

She is now helping with the restoration and painting of the elephants and has drawn up designs for one of the sculptures that she hopes will help give the works a new lease of life.

According to Mark, the experience of delving into the story of Scotland’s New Town art has been transformative.

“Not only was it a chance to spend time with dad,” he says, “it’s made me think about what art and creativity means to people. I’d be open to presenting more documentaries, for sure.”

Meet You At The Hippos, Tuesday, November 30, BBC Scotland, 10pm

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © Stewart Attwood

© Stewart Attwood