THIS month, 69 years after one of Britain’s worst post-war naval tragedies, people will remember the HM Submarine Truculent.

A new generation will also hear about it for the first time, and be shocked to learn how the submarine sank in the Thames Estuary, with 64 men dead and only 15 survivors, in January of 1950.

One man, 95-year-old Fred Henley, is the last survivor of that dreadful disaster, and his memories of it and an amazing naval career can now be read in a new book.

John Johnson-Allen, a maritime historian and another man with a lengthy life on the ocean waves behind him, has written it after many hours interviewing Fred, and he spoke to our sister title The Weekly News.

“It’s surprisingly little-known, even by Royal Naval people,” John pointed out. “I think it’s because it was so soon after the war and there was so much going on.

“At the time, however, there was a huge outpouring with telegrams coming in from all over the world. One came from the King.”

It read, “I have heard with great regret of the disaster that has occurred to HMS Truculent. Please convey to the next of kin of all those who have lost their lives the deep sympathy of the Queen and myself.”

John continued: “It was a huge thing. Sixty-four people died because of a stupid mistake.”

The books gets its grim title – They Were Just Skulls – because of the difficulty in recognising the dead after they pulled Truculent to the surface three months later.

And that “stupid mistake” John refers to indicates the actions of Truculent’s commander, Lt Charles Bowers.

“I’m a former Merchant Navy officer, and we were required to know the collision regulations inside-out and back-to-front, and so were Royal Naval officers. But clearly he didn’t,” said John.

“It was because of his mistake that the whole thing happened. He’d been appointed to submarines in 1942, he’d gone through the war and been mentioned in dispatches.

“He had been in command of submarines since 1946, having passed The Perisher, which is the course for commanders. So he should have known.”

John will attend a special Truculent event at Chatham this month, where there is likely to be great interest in his new book.

He said: “Truculent was a Chatham boat, and Fred Henley is from Chatham. In those days, the Royal Navy was divided into three home bases, Plymouth, Portsmouth and Chatham.

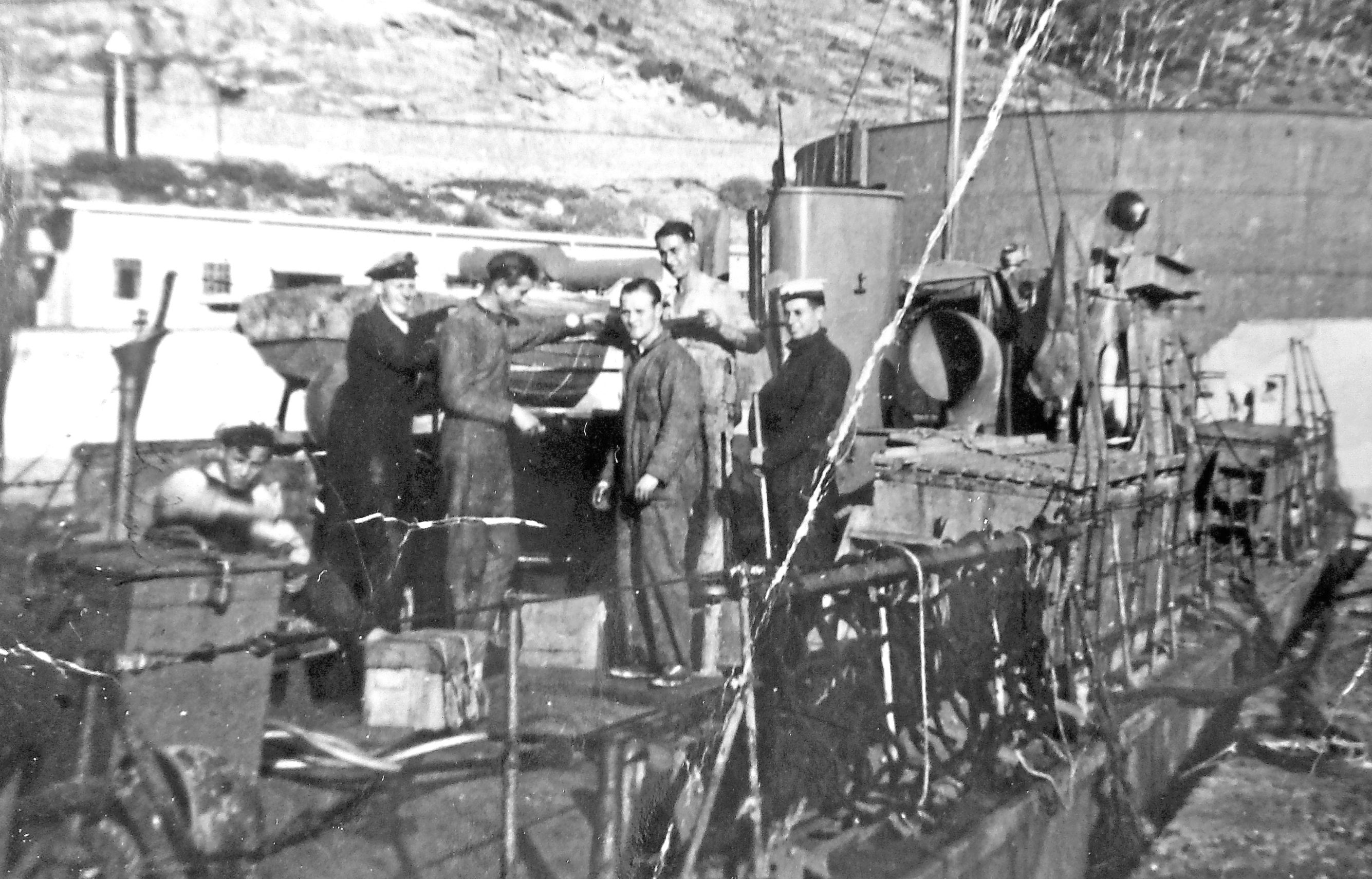

“She had served through the war, and in 1943 she had towed one of the miniature subs that attacked the Tirpitz. After that, she went out to the Far East.

“Truculent attacked the biggest ship in a Japanese convoy, but what nobody knew was that it wasn’t carrying cargo, it was carrying about 700 Allied prisoners of war. It sank and 180 were killed.

“After that, she came back to operate around the UK in the autumn of 1949. Bowers was appointed in October and Fred joined her in November.

“As was customary, she then went out on trials. And then it happened.”

As John reveals, it was a bizarre error that caused it.

He said: “She was coming back to the Thames Estuary on January 12, as the captain wouldn’t sail on the 13th because he was superstitious.

“It was cold, dark, six o’clock at night, and there was a strong tide flowing out of the Thames. By about seven, they were quite close on their starboard side to a sandbank and saw ahead of them the lights of another ship.

“It was just after this that Fred was asked to go up on the bridge with a copy of the Admiralty Manual of Seamanship, which contains all the relevant combinations of lights that ships carry at night.

“Asking your staff to bring the instruction manual to the bridge! This is where my hackles rise because they should have known.

“Because the captain got it wrong, he decided not to wait until the ship went past but to turn and cross in front of it, thinking it would stop.

“At nine-and-a-half knots with the tide under it making it go even faster, it went straight into the Truculent.”

Some, like Fred, were swept off the bridge, while many men were trapped or killed instantly.

John said: “Not all the bodies were found, but some drifted out on the very cold ebb tide, dying of hypothermia, with some bodies found in Belgium, others at Margate and Ramsgate.”

There are many other fascinating aspects to Fred Henley’s life on the seas.

But let’s hope his vivid memories of the Truculent in particular will stay with everyone who reads them.

They Were Just Skulls, by John Johnson-Allen, is published by Whittles, price £16.99.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe