Fiercely loyal, organised, political and sometimes violent, ultras are football fans like no others.

Journalist James Montague tells Laura Smith the Honest Truth about these extreme and controversial supporter groups and their impact on the beautiful game around the world.

Where did the ultras culture of extreme football fans begin?

Italy, 1968. Ultra is synonymous with Italy and the colour, pageantry, art, pyrotechnics, song and lexicon that emerged from Italian stadiums helped Serie A become the most exciting league to watch in the world. It influenced groups in Europe, North Africa and Asia.

The leader of the songs is the capo. The fans gather on the curva, the terrace behind the goal. The fans are the tifosi, derived from the Italian for typhus, an infection that can induce mania.

In truth, ultra culture is a product of globalisation; a mixture of influences from Italy, the barras bravas in Argentina, the torcida in Brazil and casual and hooligan culture in the UK.

What and who are the ultras?

“Ultra” means “to go beyond”, to go further for your team. It is a way of life that sees you completely subsume yourself into the identity and the service of a club or group. It is about showing your support through choreografia and tifos, the huge artistic displays you see before and during a game, singing songs, burning pyro.

It is a highly organised and structured group of thousands of, mostly, young men. They generally have a very antagonistic relationship with the authorities and mistrust the media. The movement is also deeply political and rallies against the commercialisation of football.

In Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, Turkey, even Ukraine, the football stadiums and the fan groups within them organised against oppression and in some cases, especially Egypt and Ukraine, played a leading role in toppling a government.

What are ultra fans like around the world?

It’s a culture of extremes. In Italy, many groups have shifted to the far right. They once had a huge amount of power within the clubs, which is anathema to British football. The Irriducibili, the far-right ultras of Lazio, virtually ran the club in the ’90s. They built their own merchandising brand, had a say over who would or wouldn’t sign for the team, be given tickets and even have keys to the stadium.

Today, in Poland, Ukraine, Russia, Morocco and Indonesia, you’ll find huge numbers, the best choreography and, at times, some pretty shocking violence.

Any memorable encounters?

Meeting Fabrizio Piscitelli, known as Diabolik, the capo of Lazio’s Irriducibili. He was probably the most important and feared figure in the Italian ultras scene for 20 years. We secured an audience with him when he’d just come out of prison on drug trafficking charges. The group is openly fascist and gave him straight-arm Roman salutes.

We spoke beside a portrait of Mussolini. Three months later, someone shot him in the head in broad daylight in a Rome park. I was also chased down an Indonesian highway by a mob of Persib Bandung ultras waving machetes. I genuinely thought I was going to die.

What impact has the pandemic had?

Ultras aren’t in the stadiums but you often see them outside the stadiums for big games. Many ultra groups also do community work and have raised money and supplies for hospitals or the poor. The ultras from Atalanta, in Bergamo, the epicentre of Italy’s outbreak, virtually built a new field hospital.

But the scene needs football matches as the focal point for their energies and identity. Another season like this would mean a lost generation but it has been remarkably resilient so far.

What about the UK?

The UK doesn’t have an ultra culture mainly because it doesn’t have the space to exist. We had our own casual culture. When the influence of ultras was seeping into German or Eastern European football in the early 1990s, we were dealing with the fallout from Hillsborough and the Taylor Report.

British football is so tightly controlled that nothing can really exist in opposition to the authorities within the stadiums. Instead, groups are flourishing in the lower leagues and that’s where you will find any nascent ultra culture today.

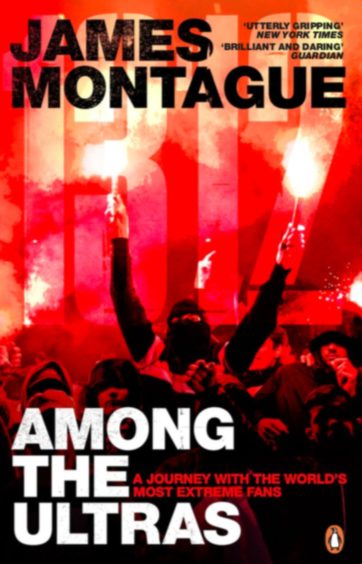

1312: Among The Ultras, by James Montague, published by Ebury Press, is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Vladimir Zivojinovic

© Vladimir Zivojinovic