THE city was the first to give him its freedom, famously tormenting his tormentors and helping to mobilise a worldwide campaign for his release.

And, when he was, Nelson Mandela’s long walk to freedom led to Glasgow where he thanked the city for its support exactly 25 years ago.

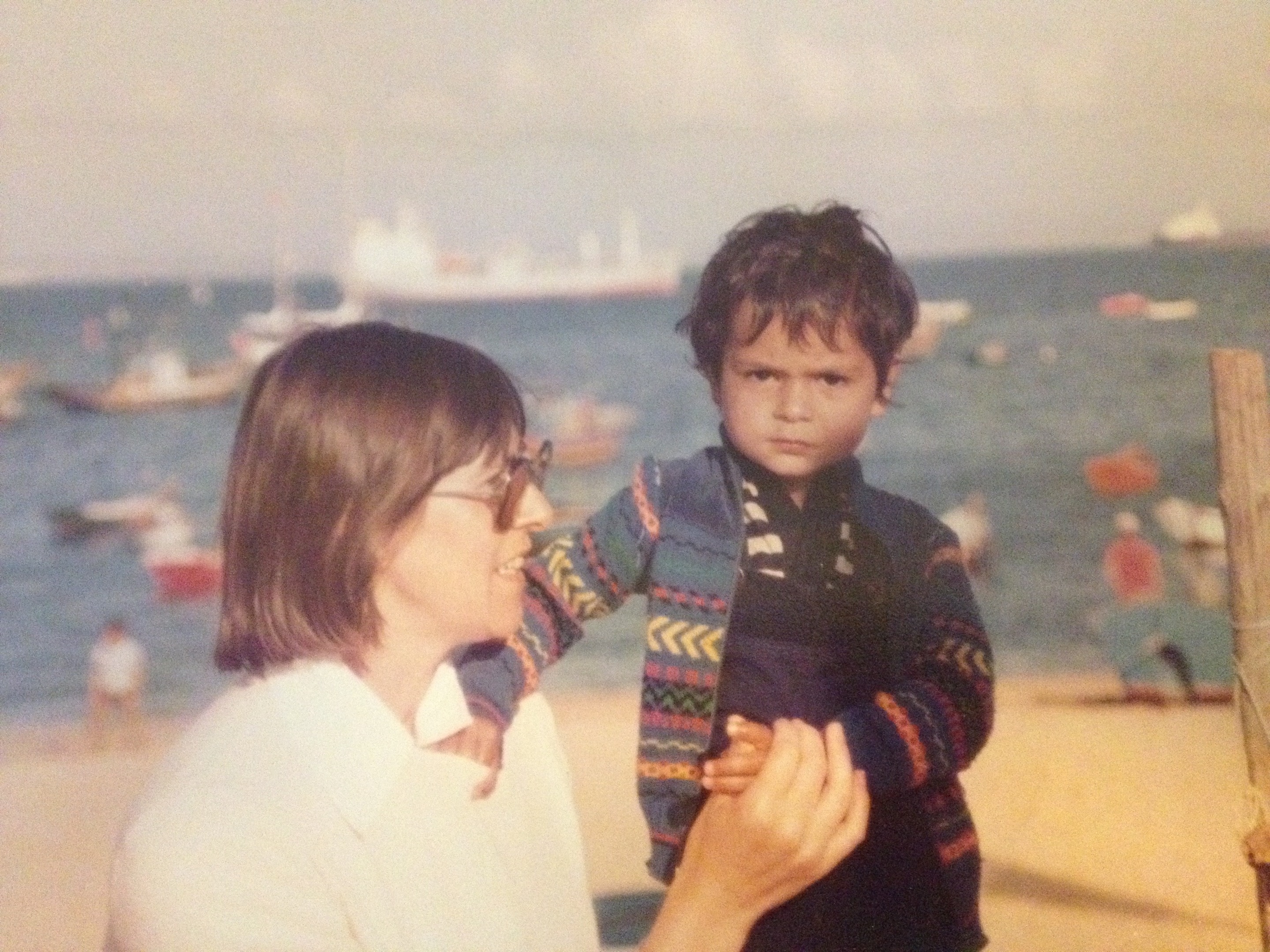

The crowds joining him to celebrate included Radha and Maggie Chetty; who had more knowledge than most of the apartheid regime in South Africa that had jailed him.

Radha had been forced to leave South Africa, where he was born, to build a new life in Scoland where he met and fell for Maggie

Now their film-maker daughter Dhivya-Kate is telling her parents’ story, which was shadowed by a regime marked by fear and repression.

Radha, an Indian South African, was one of 12 children and his parents couldn’t have been more aware of the restrictions on opportunities.

“They had two shops in what became designated as white areas. The government passed legislation that meant they had to sell up,” said Radha.

“The educational privileges given to white people were far superior. I wanted to be an engineer but I would have needed physics and I wasn’t allowed to study that because of the syllabus the government dictated.

“My parents knew it was impossible to live a decent life with dignity in that country.”

So Radha and several of his brothers and sisters were sent to study and make themselves new lives in Scotland.

It was here, while getting the qualifications at Strathclyde University he needed for what would be a successful career as an engineer, that he first met Maggie in 1965. They met again in the early 1970s and married soon after.

Even if the couple had wanted to start a new life back in South Africa, it wouldn’t have been possible.

“I couldn’t get a job because a person of colour couldn’t give instructions to someone who was white,” Radha said.

“Indian or African doctors, of which there were a few, had to work in non-white hospitals.

“But it was still heart-breaking to leave.”

Maggie insists that, work aside, they couldn’t contemplate a permanent return as a mixed-race couple. “It would have been very difficult,” said former teacher Maggie.

“It was against the law and we would have been very visible.

“When we visited the family home, it was so segregated that it was like living in India for me.

“When we went with our daughters, who’d been brought up in Scotland, they found it truly shocking.

“People literally stopped and stared. And when we took them to the beach they couldn’t understand what was happening.

“The white area of Durban beach, which was world famous, had paddling pools and slides. The Indian area was disreputable with a little shack for a restaurant. And the African area was where all the sharks were as there weren’t any shark nets.”

The Chetty family was active in the anti-apartheid movement in Glasgow and had members of the ANC (the political party aiming to give South African minorities the right to vote), who were visiting the city, stay with them.

Even though they had married here and Radha had become a British citizen, it meant rare trips back to South Africa were fraught and filled with anxiety.

“It was complicated and I found the whole thing terrifying,” said Maggie.

“We travelled a lot and even though it was a main road, the South African police could have stopped us at any time.

“They were vicious. They absolutely hated people who opposed apartheid. It was wonderful to meet the family, but it was so frightening.”

When news of Mandela’s release came in February 1990, Maggie and Radha joined the throngs who gathered to celebrate at Nelson Mandela Place – the street, once St George’s Place, was renamed and, just by chance, was where the South African consulate-general was based

“The movement in Glasgow had been working towards this for years and it was such a joyous occasion,” said Radha.

So, when Mandela came to Glasgow – the first city to offer him its freedom when he was still in prison – on October 9 1993, (a year before he became president), the Chettys were right to the forefront, with Radha one of his stewards.

And they were then able to witness a South Africa whose fortunes were transformed.

“When we went back on subsequent visits, we could see so many changes but there is still a legacy.

“The geography of apartheid remains. The area where Radha’s parents’ lived is still an Indian area and white areas are still pretty much exclusive with beautiful houses for white people.

“In the city centres of Johannesburg or Durban you’ll see couples mixing, but it’s much more difficult for them to mix back in their own communities.”

For daughter Dhivya-Kate, making the programme and taking her mum and dad home, was a labour of love.

She said: “It was often difficult asking such probing questions of my family. I felt guilty about making them revisit emotional or difficult things in the past.

“But the wider story is not about my parents – it’s about fighting racism and inequality, taking a stance, about the migrant experience, where ‘home’ can be in two places.”

Glasgow, Love and Apartheid, BBC2 Scotland Tuesday 9pm.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe