When Jim Ballard heard news of the world’s most treacherous mountain being conquered in the most dangerous conditions, he raised a silent salute.

Almost 25 years after his wife Alison Hargreaves died on K2, he knew she too would have been thrilled at the feat of 10 Sherpas who became the first to reach the summit in winter.

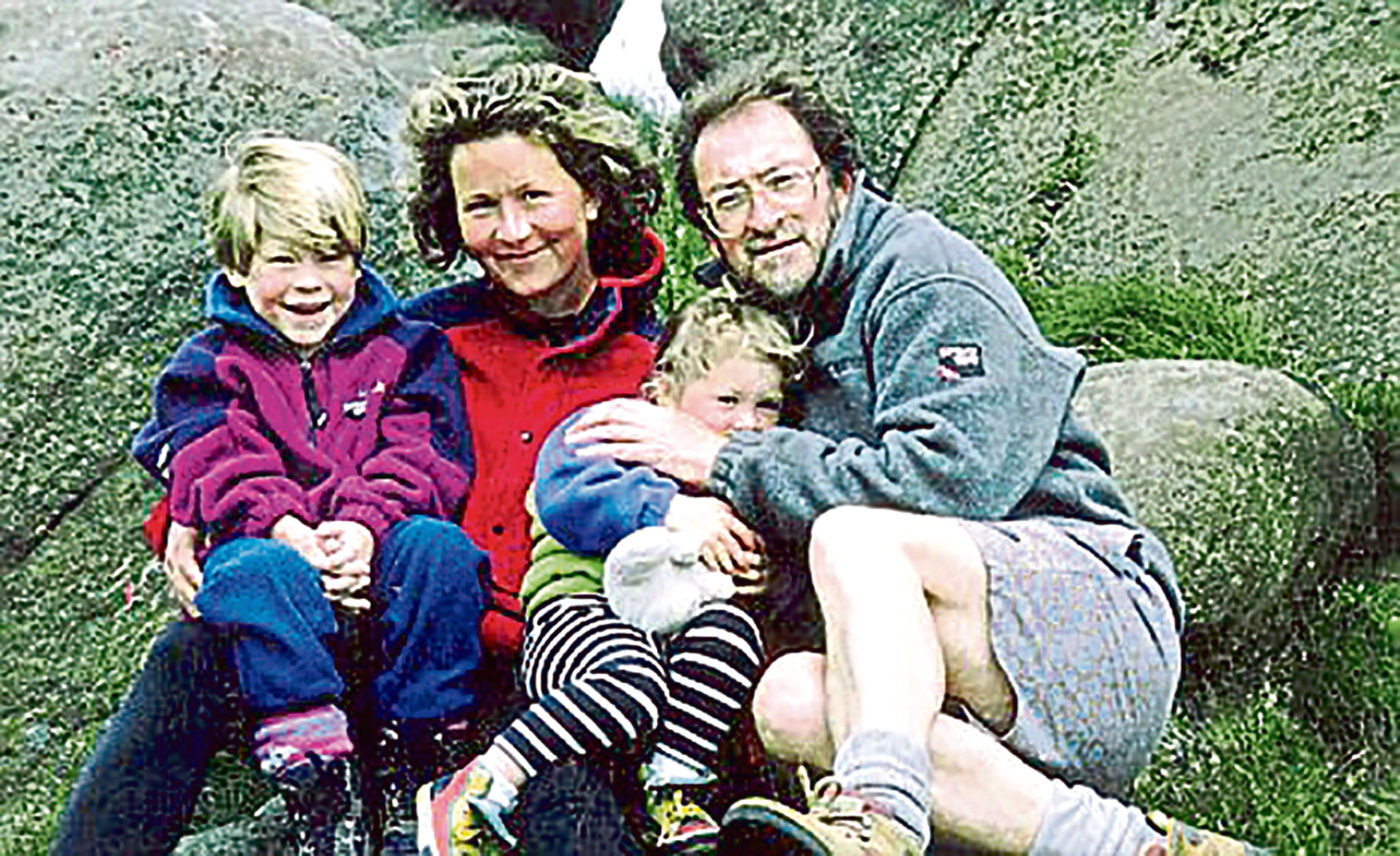

She was just 33 when she died shortly after clinching a world record on K2 in 1995. She was the first woman to scale, unsupported, the planet’s two highest peaks – Everest, followed by K2 three months later. It was her last mountain. She died in a storm on her descent, along with five others when the couple’s children, Tom and Kate, were just six and four.

More than two decades later, Tom, another courageous mountaineer, would die on Nanga Parbat, another Himalayan peak and the world’s ninth highest. He was 30. His Italian climbing partner, Daniele Nardi, 42, also died.

Speaking publicly for the first time since the confirmation of Tom’s death in 2019, Mr Ballard – formerly of Spean Bridge near Fort William – told The Sunday Post his wife and son would have been thrilled by the Sherpas’ ascent last week.

“Alison and Tom would have taken their hats off to them,” he said.

Also a climber, Mr Ballard, now in his early 70s and based in France, where he spent Christmas and New Year climbing with his snowboarder daughter, now 28, revealed: “I have not remarried. It is very difficult when you lose somebody close to you, an awful lot of people have found that out in the last year.

“It sounds trite to say Alison and Tom died doing something they loved, but it is true. Although I am not altogether sure you come to terms with losing a child. It is not supposed to happen. They are supposed to wave you gently on your way to Valhalla; or wherever it is. It is not correct losing children.

“But life does have to go on, as one friend of mine said, ‘The sun will still shine and the grass will still grow’. So you just have to learn to accept it. I never complained with Alison and I’m not going to complain with Tom. They chose the life they wanted. I spent all my life in the mountains, Kate spends all her life in the mountains, it is what we choose to do.”

With the bodies of his lost family still on the mountains they loved, he admitted: “I think back 25 years to Alison and I think back two years to Tom, and that is the really sad thing – the opportunities they have not been able to take.”

He believes they would have special praise for the K2 team’s 37-year-old leader Nirmal Purja, MBE, a former Gurkha and UK Special Forces member, who burst on to the climbing scene in 2019 when he scaled all 14 8,000-metre peaks in six months and six days, shaving more than seven years off the world record.

Mr Ballard said: “That young Nepalese climber has had a very successful year already and has shown what a fantastic, strong and able young man he is. To see a summit picture of them without even their hoods up – you wouldn’t expect that even if you were climbing in the Alps now.”

The team had enjoyed an unusual window of good weather. “The important thing, as with all climbing, is taking the opportunity – and they took it,” said Mr Ballard.

“Things have changed, even in the couple of years since Tom died, and certainly in the years since losing Alison. Weather forecasts are getting more accurate and it’s easier to gamble on it if you have some experience in interpreting what the forecast says.

“These Nepalese boys were strong enough, and not so single-minded if the weather had started to turn. Because they had laid fixed ropes and fixed camps up the mountain, they would have had a good chance of escaping. But they didn’t need it, they had perfect weather and got to the summit. One has to congratulate them on their ability.”

Despite their own skills, his wife and son were not so fortunate. Alison had solo climbed all of the great north faces of the Alps in a single summer season. She had even scaled the notorious north face of the Eiger while six months pregnant with Tom. Her spectacular record of success included the 22,349ft Ama Dablam in Nepal.

In 1995 she intended to climb unaided the three highest mountains in the world – Mount Everest, K2, and Kangchenjunga, becoming the first woman to reach without bottled oxygen and Sherpa support the 29,029ft tip of Everest and the 28, 251ft peak of K2. Survivors confirmed she reached the summit and said they believed Alison had been making her way down when she was blown away by fierce winds.

Tom – crowned the “King of the Alps” after he became the first ever person to solo climb all six major north faces in one winter – had attempted the Nanga Parbat summit in winter several times before his tragic attempt. Concerns for him mounted after an avalanche in the area at the end of February 2019. His death was confirmed in March.

Mr Ballard said: “The old Tibetan saying, ‘Better to live one day as a tiger than a thousand days as a sheep’ is true. We all chose, in our family, what we wanted to do and go on with doing it.

“It’s a bit like that young Nepalese ex Gurkha. He saw a set of things that he wanted to do, climbing big mountains, and he has just carried on.”

Mr Ballard is now writing a book about his son who, had he lived, would undoubtedly have gone on to even greater achievement. Along with his daughter Kate, a Swiss qualified ski and snow boarding instructor, Mr Ballard is taking part in a BBC and Universal Pictures documentary about his family’s life, which he hopes will be released later this year. Aptly, he said its working title is Children Of The Mountains.

And he believes the mountains are the most fitting final resting place for his lost loved ones. Stoic in his acceptance of their near-impossible repatriation, he added: “There is a chance, particularly since Alison has been dead for 25 years, that some of the other bodies of those who died with her have turned up. They do from time to time turn up on big mountains particularly in these days of global warming…. and it is not a nice thought for me personally.”

He remembered Lochcarron mountain guide Martin Moran who was leading a group that went missing following an avalanche on an unclimbed and unnamed 21,250ft Himalayan peak in 2019. Seven bodies were repatriated, but Mr Moran was not found. Mr Ballard said he was shocked at how the recovery was handled: “The way they filmed them digging up bodies upset a lot of people. Both Alison and Tom would have been appalled.”

Similarly, he said, they would be concerned by the growing number of amateur climbers on commercially-guided trips to K2 who are reported to come with Instagram accounts and gallons of oxygen but little experience of peaks over 8,000m.

“There are people who have more money than time,” he said. “And using professional mountain guides, they can get up mountains that are more difficult than they would normally tackle. That certainly happens in the Alps. It now happens in the Himalayas.

“The problem is when things go wrong at altitude, as sometimes they do, you can end up with a disaster like the one that happened on Everest that became a series of books and a Hollywood film.”

Eight people died on Everest in May, 1996 while attempting to descend from the summit. The tragedy raised questions about the commercialisation of the mountain.

Mr Ballard said: “K2 is another problem. One of these days, sadly, the weather will come in as unexpected as it did with Alison and no matter how good a climber you are, unless you abandon your clients – and you shouldn’t do that – then you are going to die too.

“Both Alison and Tom would be very worried about the commercialisation of K2, but it was bound to happen. That is exactly what has happened with Everest. The thing that generally stops people on K2 – and this year it hasn’t – is the weather.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © PA

© PA