When a 16-year-old Lenny Henry won New Faces in 1975 with impersonations of Frank Spencer and Tommy Cooper, he couldn’t have imagined he’d become an award-winning Shakespearean actor and charity ambassador with a knighthood.

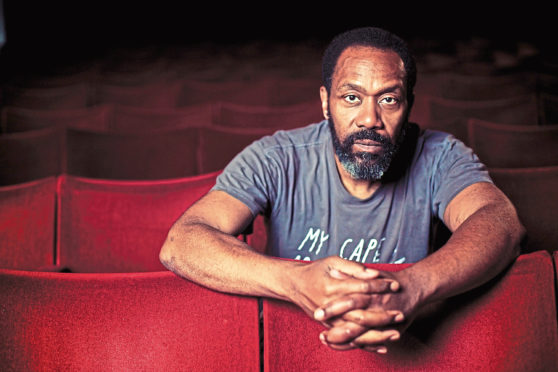

Now 61, Sir Lenny Henry – comedian, actor and Comic Relief honorary life president – is reflecting on his early years as we discuss his new memoir, Who Am I, Again?

In it, he charts his formative years growing up in Dudley under the watchful eye of his larger-than-life mother, Winnie – the rock of the family and “Jamaican Wonder Woman” – who came over to the UK in the 1950s in search of a better life and “H’integration”.

“Mum had a really good sense of humour and was a consummate storyteller,” he recalls. “She had this glorious laugh. I used to think: ‘Wouldn’t it be great to make somebody laugh like that?’

“You can psychoanalyse it now, but this whole thing about me wanting to be a comedian could have been about trying to please my mum, trying to make her laugh, trying to be seen.”

Lenny was the fifth of seven children. Life was noisy, busy, and often there were blazing arguments between his parents.

He suffered racist jibes at school, countering them with humour and developing random impersonations of a Jamaican Scooby-Doo and Deputy Dawg from Dudley, before moving on to David Bellamy, Tommy Cooper, Max Bygraves and Frank Spencer.

He honed his impressions to entertain punters at the town’s Queen Mary Ballroom, local pubs and clubs, and got himself an agent – and a slot on New Faces.

How did he cope with fame at such an early age?

“Not very well,” he admits. “I had an ‘ignorance is bliss’ attitude. It was literally like being attached to a firework that had had the blue touch paper lit.

“There was no way to process anything. I was really young and gullible, so everything was with this gung-ho, get-stuck-in attitude, without understanding the seriousness of decisions that were being made in split seconds.

“I drank underage, went out and when I discovered London – which was so different from Dudley – I almost exploded, and then when I went to New York for the first time, I nearly exploded again.”

So, are youngsters in talent shows today better protected?

“No,” Lenny says, “it’s worse now because kids are younger. Kids on The Voice are just thrown into the spotlight in front of seven million people. You sing your heart out and if you lose, how do you pick up the pieces? What happens then? That’s years of therapy.

“They need a crew around them, they need to be protected mentally and physically, kept fit and on top of things. It’s no wonder people break down in their mid-20s if they started when they were 14.

“If there’s nobody watching out for you, it can lead to grave mistakes. I really wish somebody had been watching out for me.”

But Lenny draws a line between talent shows and reality shows.

“That’s not really about talent, it’s just about people watching people behave,” he explains. “If you have civilians on television being filmed, then editing them together, that’s going to have a terrible effect on their psyches.

“Shows should be regulated and monitored by people who know what they’re doing, rather than having therapists doing punditry. People should receive counselling. You’re laying your soul bare.

“I wouldn’t be here without a talent show, but there’s a pastoral element that needs to be introduced,” he insists. “There’s a responsibility broadcasters have to young talent.”

After winning New Faces, Lenny signed up to do The Black And White Minstrel Show – the first actual black person in the line-up – where he stayed for five years.

“It was mentally bruising but kids have a tendency to endure,” he admits. “I sort of pretended it wasn’t happening and got on with working in a big theatre.

“Even though the guys who came in were white and lovely and nice to me, the truth of the matter is that I was stuck in this show that was a racial anomaly and in my heart, I hated being in it.”

He’ll never forget the racism he has endured – from his front door being smeared with excrement by the National Front during his marriage to Dawn French, to the times people spat on their fingers, rubbing his face and saying: “Ooh look, it doesn’t come off.”

“I do wish I had stood up to racism more,” he writes.

He also charts the revelation that his father, Winston – who had a pretty cold relationship with his son – wasn’t his birth father.

“When I was 11, Mum said: ‘Oh you should go and help out with your Uncle Bertie down the road’ and suddenly I was down there. I think she felt I should just know who my birth father was. That’s all, nothing sinister.”

At 12, his stepbrother told him the truth. “It was a bit like having a massive cosmic carpet whipped from under your feet,” he recalls. “There was a real sense of displacement and disconnection and weirdness – a feeling of shame; a feeling that I had two dads and nobody else had two dads.

“This kind of story is in lots of families, but I didn’t know that. It felt like a massive burden.”

Now embarking on a nationwide tour, in which he’ll relate stories from the book, performing live still gives Lenny a huge buzz.

“I love comedy, but since 2010 I’ve played Othello, Arturo Ui, I’ve been in Educating Rita. I want to do more acting,” he says.

He reckons the whole life story will take three books. The first takes us up to Tiswas and Three Of A Kind, but doesn’t feature his 25-year marriage to Dawn French, or his current relationship with theatre producer Lisa Makin.

“If you try to cram 61 years into one book, that’s a lot of pages!” he says. “That amount of memory mining is like exhuming bodies; it’s a lot of work. I want to pace myself.”

Who Am I, Again? by Lenny Henry is published by Faber & Faber, priced £20.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © BBC / PA

© BBC / PA