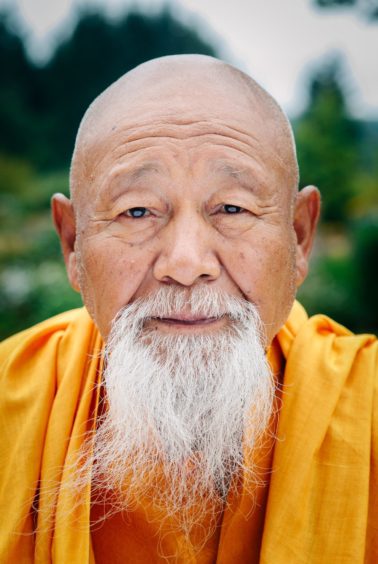

When Lama Yeshe Losal Rinpoche first came to Scotland more than five decades ago, the young Tibetan was far from the calm and joyful Buddhist monk he is today.

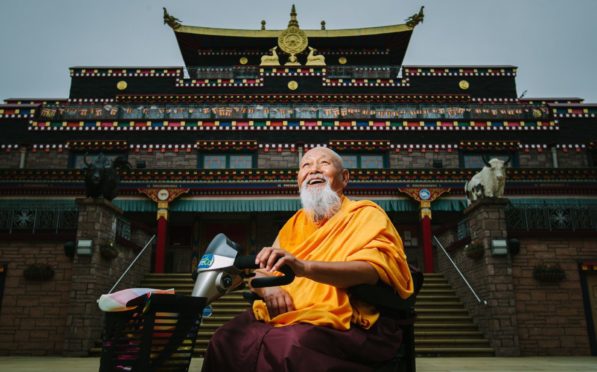

Now 77, he remains a driving force behind the Kagyu Samye Ling Monastery, the first Tibetan centre in the West, which has been nestled among the rolling green hills of Dumfries and Galloway since 1967.

He admits, however, his own journey from a self-proclaimed “lazy and selfish waster” to a peaceful and pioneering abbot was a long and rocky one, which saw him rebel for much of his early life as he embraced some of the wicked ways of Western culture.

“I have learned your way of life, so I am an expert! I hope my life story will help all Europeans, whether young or old. I am living proof how Buddhism will benefit you,” he said, from inside Samye Ling which has been closed to visitors during the months of the pandemic to protect its 46 residents.

Life in a Buddhist monastery was a fate Lama Yeshe was deeply at odds with as a child. Born in 1943, he grew up as Jamphel Drakpa in the idyllic, rural mountain village of Darak in Eastern Tibet. Aged 12, he reluctantly left his family to join his brother, Abbot Akong Tulku Rinpoche, who was already head of the mountaintop Buddhist monastery Dolma Lhakang.

Three years later, the Chinese Army drove them from their monastery and towards a harrowing 10-month journey through the Himalayas.

The brothers bravely endured starvation and extreme fatigue and were among just a handful of 300 refugees to survive Chinese bullets during a desperate attempt to cross the Brahmaputra River to safety in India.

After nearly dying of tuberculosis in a Tibetan refugee camp in India, a grieving and disillusioned Lama Yeshe, who would never see his parents or family home again, found refuge but little solace in a Buddhist school in northern India.

In 1969, he joined his brother in Scotland, where Akong was setting up a new monastery near Eskdalemuir, deep in a Dumfriesshire valley. But Lama Yeshe rebelled against his brother, Buddhism and his new life in “wet and grey” Scotland.

Akong became a lightning rod for his brother’s pain and frustration as Lama Yeshe ignored the teachings and wisdom of the Buddhist masters who visited Samye Ling and instead embraced Western ways. First in Eskdalemuir, and later London and New York, he developed a taste for whisky, gambling, fast cars and women, much to his brother’s displeasure.

“When I first came to Scotland, a local taught me how to drink whisky. I could drink a whole bottle in one sitting. I did exactly what the Europeans did,” he recalled. “I blamed my brother for everything I had been through, for never seeing my parents again, his strict teachings, everything that was wrong in my life.”

Then on a fishing boat in Orkney, Lama Yeshe was photographed with a catch of fish that broke a central rule of Buddhism to respect life and refrain from killing. It shattered his brother’s heart and inspired Lama Yeshe to change his ways.

“He told me he had vowed to our parents to look after me and that he couldn’t bear to think of one day seeing them again because he failed them. That twisted my heart and, inwardly, I made a vow to change and to make my brother proud.”

In 1980, he took his first true step on his spiritual path when His Holiness the 16th Karmapa – spiritual head of the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism – ordained him as a Buddhist monk, and he became known as Yeshe Losal.

He then spent five years in solitude at a Buddhist centre in Woodstock, in the USA, to calm his mind and reconcile with his past. “It helped me change and calm my ignorant mind, find peace and harmony. Now I do not get angry,” he said. “My mind is completely free, like an infinite sky with no clouds.”

On his return to Scotland, Lama Yeshe helped his brother grow Samye Ling into a world-renowned Tibetan monastery. The tranquil and colourful site has welcomed visitors from around the world, until it closed its doors earlier this year due to the coronavirus pandemic. He said: “When we first came here, we received telephone calls from people telling us we were foreigners and should get out. Now we bring much money to the local economy and many tourists to the area.”

Lama Yeshe was appointed as an abbot of Samye Ling in 1995. He has pioneered temporary ordination within Tibetan Buddhism, and lobbied for women to be ordinated as Gelong nuns, so their position within the monastery is equal to male monks. But his proudest achievement lies in the tranquil stillness of Lamlash Bay, on the Holy Isle near Arran. Samye Ling purchased the tiny island in 1992, where Lama Yeshe established and continues to direct the Holy Isle Project, which includes a Centre for World Peace and Health that runs meditation retreats open to people of any faith.

Today, the Tibetan exile is proud to call Scotland home. He added: “Scotland is the most beautiful country in the world. It reminds me of my home in Tibet. It is calm, quiet, with few people, animals and rolling hills. I promote Scotland wherever I go.”

Lama Yeshe recounts his life journey in his new memoir, From A Mountain In Tibet: A Monk’s Story. Despite everything he has suffered, he says his story is a hopeful one and that can inspire others.

Spending just a short time in his joyful company, and hearing his extraordinary personal journey, makes his unmovable positivity, forgiveness and tranquillity even more inspirational.

It is this ability to relate to others that the influential abbot believes helps him support all those who go to the Samye Ling monastery for help and guidance, from frazzled high-flying executives to people struggling with addiction.

“My book is all about reaching out to others. My students used to tell me that, because I was a Lama, we were not the same, our troubles were not the same. I’d tell them, you are wrong because I was not always a Lama. You can relate to me as an ordinary person because of what I have been through and overcome.”

His words of wisdom can offer some solace amid a global pandemic that has inflicted pain, loss, loneliness and uncertainty on many.

“Lockdown forced many people into solitude. I’ve been doing solitude retreats for much of my life. This gave me the opportunity to clear my mind and be happy,” he said. “Buddha teaches us self-liberation, that your need for superficial things and money will never fulfil you. Buddha says we should abandon that materialistic world for a more realistic world.

“Look inwardly to find inner peace. In Buddhism, mind is king. If we can change our mental orientation then everything else will follow.”

Lama Yeshe says Buddhism, practised by 500 million people worldwide today, also helped him come to terms with losing his parents and the shocking death of his older brother, Akong, who was murdered in China in 1993 over a money dispute.

“I never saw my parents again. My father and brother were tortured for 15 years because of who my brother and I were. My father and mother died with a lot of suffering. But you must learn to forgive. I am very positive human being. I never allow myself to be negative. My bad experiences don’t exist any more because I don’t dwell on them. This is Buddhist wisdom.

“My advice is to not dwell on the past or worry about the future but come back to the present moment. I teach people compassion, love, kindness, tolerance, forgiveness, so they can feel liberated. Use love and kindness to subdue your own anger, subdue your own negativity and encourage love and kindness in others. This will help you become better person. This is what we all need to remember.”

From a Mountain in Tibet: A Monk’s Journey, Penguin, is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley