It was once the backdrop to thrilling sporting spectacles but became a concentration camp where 20,000 men and women were held, tortured, raped and executed.

Oscar Mendoza, then a teenage student, was among those detained in the Santiago stadium, where he was beaten and branded an enemy of the state in the Chilean dictatorship.

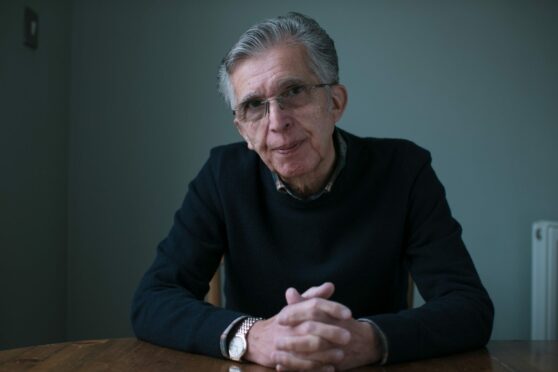

Through his lawyer he managed to get a visa to escape to Britain where he built a new life. Today, Mendoza, 68, is planning to return to his homeland to mark the 50th anniversary of the military coup that deposed socialist president Salvador Allende, a move encouraged by the White House. General Augusto Pinochet took control and would lead a brutal regime for 15 years.

Mendoza will join other refugees returning for national commemoration ceremonies. Now living in Lanarkshire, he looked back and thanked the UK authorities of the 1970s for offering him sanctuary.

“They were different times where the Labour government welcomed between 2,500 and 3,000 refugees from Chile,” he said. “Every day I thank the people for making me feel at home in Glasgow.”

Two weeks after the coup, he was detained by the military and endured the constant threat of violence.

“I was beaten. They would order us out of cells in the middle of the night into a freezing cold stadium in our pyjamas, sometimes beating us as we went. Among us were many fathers with families who suffered military torture and who disappeared.

“It was something you had to endure to survive. I was then forced to appear in front of a military court, sentenced to almost two years in prison and exiled from my family and country. They did not produce evidence to suggest I was guilty. Those chosen to appear in a military tribunal were picked at random.”

Thousands were detained, executed and disappeared, while mothers had their babies stolen in forced adoptions under Pinochet. Generations of families were torn apart from 1973 until the regime fell in 1990.

Mendoza’s lawyer applied to the UK for a visa at the time when the concept of sending refugees to third countries – like the UK Government’s plans to fly asylum seekers to Rwanda – while visa applications were processed was never contemplated.

Testament to the times is a report in Hansard parliamentary transcripts that revealed their speedy resettlement: “The full resources of the employment and training services, including professional and executive recruitment and the Training Opportunities Scheme, are available to assist.”

Leaving his beloved Chile at 21 was heartbreaking for Mendoza. Only the intervention of a cousin in the military police allowed him to see his family for 30 minutes before he was forced to climb the steps of the aircraft taking him to the UK. He was one of more than 200,000 Chileans who were forced into exile, many never to return.

Scottish supporters of victims of torture and internment welcomed him to Glasgow where he found sanctuary, work and eventually the chance to complete a university degree.

Childhood English lessons from an Irish teacher, based in Chile, helped Mendoza.

Now living in Bothwell, married with two sons and a granddaughter, he recalled: “I did not want to accept I would never live in my country again because to be exiled is to die a little. It means having everything you love taken away from you – your family and your country.”

His first years in Scotland were marked with post-traumatic stress and Mendoza said he made it through the toughest times thanks to loving support from his wife.

“I did suffer PTSD for several years and was so angry and depressed I was unable to accept a place at Strathclyde University, offered soon after arrival,” he said.

“A medical charity that helps victims of torture was invaluable and that treatment of Chilean refugees advanced the care of other refugees.

“Counselling and talking therapy did not exist so much back then but have evolved since. I felt rage about everything that had happened. My best friend had been killed by the regime.”

Mendoza worked in a shop before gaining a degree in social sciences and economics at Glasgow Caledonian University and moving back into a retail management post before starting a career with humanitarian charities, including the Scottish Catholic International Aid Fund, where he headed up overseas projects.

He then moved on to Mary’s Meals, which feeds thousands of children in the developing world. Another job was with the National Lottery Community Fund, helping good causes.

In 1988 he was able to return to Chile but was struck by the change in the place. “I was able to see my parents which was wonderful but it was not remotely like the country I had grown up in and loved.”

Of the challenges facing today’s refugees, he said: “We still encountered racism in the 1970s but refugees now have greater hurdles and their numbers are bigger. Brexit has impacted on this.

“People make a big distinction between migrants and refugees escaping persecution, which is not good. Refugees are invaluable because we have an ageing population and we need young people to work and contribute to society.

“I love Scotland, not least because my family and many good friends live here and Glaswegians have been exceptionally welcoming. Having a good marriage for 46 years has been a blessing. Today I feel Scottish and Chilean.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe