In Scotland we have “hills”. We don’t call them mountains. Compared to the peaks of Himalaya they’re admittedly modest. But they’re still precious, much respected and mostly unspoilt. Would that the same could be said of Himalaya.

Pronounced like “Somalia” (and, by those in the know, never like “Malaya”) Himalaya boasts five of the world’s highest mountain ranges – from the Afghan Hindu Kush and the Pamirs in the west to China’s Tien Shan, Pakistan’s mighty Karakorams and the eastward sweep of the Great Himalaya itself. On physical maps all these ranges come together in a big splodge of white and purple bruising in the heart of Asia. This is Himalaya. The word means “land of snow”, and with an average height above sea-level of over 13,000 feet, it’s our only high-altitude eco-zone. Worth protecting, one might think.

I first fetched up there on a short fishing trip to the Kashmir valley in 1965. Untroubled by midges, the angler here casts a fly against a snow-clad backdrop of peaks and glaciers. “If there is paradise on earth, this is it,” the Mughal Emperor Jahangir had declared when overseeing the creation of the first of the valley’s famous water-gardens.

I returned the following year and stayed six months in a houseboat moored on a lotus-choked lake. To pay the rent I began writing. The clatter of the portable’s keys competed with the mewing of kites and the piping of the kingfishers perched on the electricity wire. At the time Kashmir was enjoying a lull in the hostilities which had plagued it ever since the British left. India and Pakistan had fought one war over the state in 1947 and another, which never reached the valley itself, in ’65. Kashmiris were now free to do what they did best – wrangle over politics, sip glasses of aromatic tea and practice their outrageous salesmanship on the tourists.

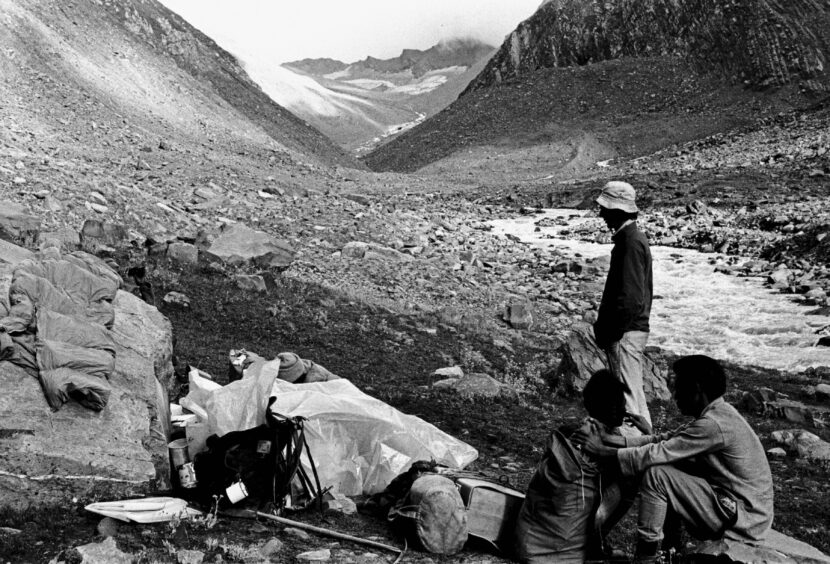

In 1970 I was back again after a tramp through the hills from Simla. Commercial trekking was still in its infancy. A friend and I had watched our suitcases being roped to whatever carrying frames the hired porters could procure, then with a sack of flour and a lot of sardines we set off for the high passes.

We were gone for about five weeks. Handicapped by a combination of amoebic dysentery, ignorance of rock climbing and the absence of an ice axe, we took our time. The prospect of Kashmir kept us going. It was the promised land, and it did not disappoint. The “Ceasefire Line” between Indian-held territory and Pakistan-held territory was about to be renamed the “Line of Control”. It looked set to become permanent. From a flotilla of double-deck houseboats a UN force of Scandinavians was monitoring the stand-off. Tourists were as welcome as ever, many of them now Indians. As Hindus they were wary of the Muslim Kashmiris, but sectarian strife was rare and guns even rarer, both being bad for business.

It was a different place by the late 1980s. The canals were silting up and the lakes were smothered in weed. Police posts and fortified checkpoints blocked the roads. A demolition squad looked to have run riot in Srinagar, the capital, and the giant plane trees beside the lakes had been de-limbed for firewood. Where once there were rice fields and pasturage there was now triple fencing, gun emplacements and row upon row of army tents. Perhaps half a million Indian troops have been stationed in Kashmir for the last 35 years, but their presence is now less to deter Pakistani incursions than to contain Kashmiri “terrorism”. Primed by a more assertive Islam and ongoing conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, a new generation of Kashmiri activists halted the trickle of tourists by challenging Indian rule with a home-grown intifada.

To write a history of Himalaya’s exploration I had already quailed before the prospect of the Karakorams in that part of the former Kashmir state held by Pakistan. Then known as the Northern Areas (and now as Gilgit-Baltistan), this most scenic of regions had just been made more accessible by the construction of the Karakoram Highway over the mountains to Chinese Xinjiang. As yet landslides and avalanches were keeping the traffic to a minimum, though the trail of abandoned vehicles and discarded pots of instant noodles warned of the eyesores to come.

In 1990 I was back in Himalaya to make a radio series about the Himalayan kingdoms. Nepal had been the obvious first stop, but there too civil strife was imminent. Ethnic insurgents and Maoist revolutionaries were just beginning to engulf the countryside and destabilise Katmandu’s always fragile governments. With the 2008 abolition of Nepal’s monarchy, the largest of the Himalayan kingdoms would cease even to be a kingdom. Sikkim had long since been gobbled up by India and only neighbouring Bhutan still entrusted its sovereignty to a sovereign.

Equally worrying, though, was the impact mass tourism was having. As Nepal’s communists opted for a role in government, tourist arrivals recovered exponentially. By 2018 they exceeded a million a year, a figure that excluded perhaps as many again who, as Indians, have unregulated access by road or rail. Nepal needs this influx. A million Nepali jobs depend on the million-a-year visitors, and the foreigners’ spending accounts for around 8% of the country’s GDP. Much of this benefits Nepali families directly. Locally run home stays, internet joints and tea shops now jostle with would-be hotels along whole sections of the Everest and Annapurna trails. Trekking agencies and equipment outfitters clamour for clients in Katmandu. Portering and guiding is open to anyone, old or young, male or female.

Climbing is more specialised, and the permits required for the great peaks are much more expensive. A summiteering expedition may cost from $30,000 to over $200,000. Success is by no means guaranteed, yet such is the demand for slots, and such the revenue they generate, that permits may be being dispensed too readily. In 2019 photos showing a 500m long conga of Goretex-clad hopefuls queueing on Everest’s summit ridge went viral. According to a US authority, “more than 600 people summit per year…and more than 200 dead bodies, too costly to remove, remain in plain view, a particularly dramatic kind of human waste”.

Other forms of human waste leave base camps looking like landfill sites. In the Karakorams, recent reports show K2 soaring above the tangle of discarded tents, ropes, poles and plastic bottles one might find on the morning after a pop concert. Scaling Himalaya’s loftiest peaks is not the redemptive experience it once was. Nor even is pilgrimage. In 2011 a visitor to Mount Kailas in Tibet found the pilgrims’ circuit of this most revered mountain “littered with rubbish – juice packets, biscuit wrappers, aerosol tins, sanitary pads, cigarette butts and Pepsi bottles”.

It doesn’t have to be like this. In Antarctica, another of the world’s most distinctive eco-zones, international supervision ensures participating nations respect the pristine environment and return all but compostable waste to wherever it originated. Himalaya enjoys no such protection. Too many nation states are involved, too many conflicts smoulder on, and too much investment is at stake. Antarctica has no Antarticans, Himalaya hosts ever more Himalayans. In Tibet new roads and railways attract Han Chinese immigrants plus the devastation that results from unbridled mineral extraction. The Changthang, Tibet’s “empty quarter”, is already dotted with pop-up townships. Kashmir awaits the opening of its first ever rail link to the rest of India.

Inward investment could conceivably reconcile the locals to inward rule. The tourists may yet return to “paradise on earth”; Everest’s “mountains of rubbish” may yet be binned and banned.

John Keay is a historian, travel writer, and specialist in Asian affairs. His book Himalaya: Exploring The Roof Of The World is published by Bloomsbury

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe