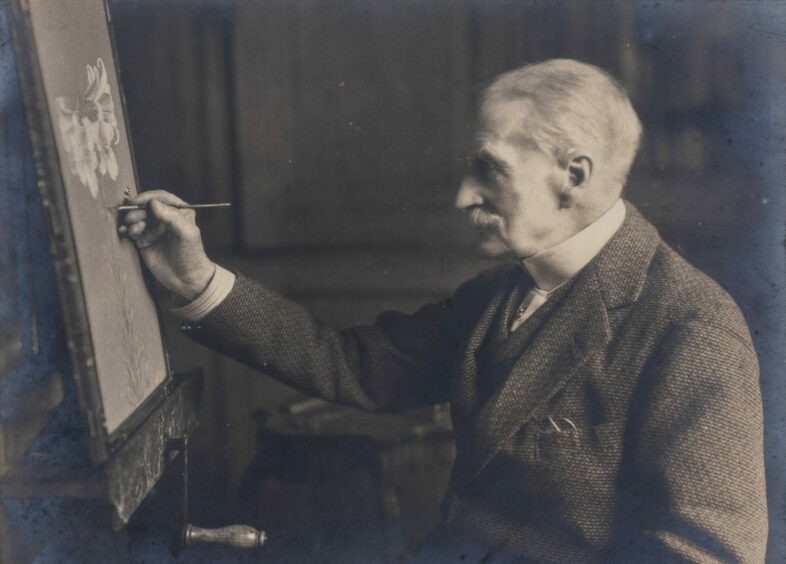

It is a stunning summer’s day and, for the first time since his boyhood, a distinguished gent, now in his 71st year, is moved to pick up his paint brush.

And, at his easel, in the middle of his beautiful and exotic garden, he captures the plants that surround him from all across the world; rhododendrons from Asia, Californian tree poppies from the US, and monkey puzzle trees from South America.

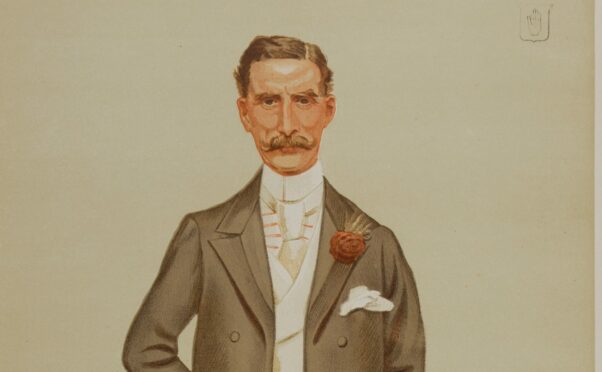

Sir Herbert Maxwell, a novelist, painter, historian, sportsman, long-serving MP and nature enthusiast, was born in Edinburgh in 1845 and died at his Dumfries and Galloway home at 92 in 1937. Of all his achievements, perhaps the most enduring is his work detailing the world of Scottish horticulture, a lifetime passion to be celebrated in a new exhibition.

On the coast of the Irish Channel and benefitting from the effects of the North Atlantic Drift, many parts of Maxwell’s native Galloway have a more stable climate than the rest of Scotland, rendering it cooler in summer but warmer in winter than other parts of the country. This allows plants and flowers more used to an exotic climate to thrive there, while normally Scotland’s annual cold wintery frosts would literally nip their growth in the bud.

As a result, Logan Botanic Garden is home to some of Scotland’s most exotic plants, trees and flowers from countries as far flung as New Zealand and Chile. Maxwell was perhaps the first to use the climate to an exotic horticultural advantage, and was responsible for planting flowers and trees in his estate garden that had never been seen before in Scotland.

Logan Botanic Garden’s curator Richard Baines told The Sunday Post how he was inspired to create an exhibition around Sir Herbert Maxwell’s horticultural work after visiting Monreith House, Sir Maxwell’s former private home.

Baines said: “Sir Herbert was a very busy man, and how he managed to fit it all in, no one really knows. One of these really eminent passions was as a gardener and as a horticulturist, and at the age of 70, he took up painting again after being trained in it during his youth, and it was said he would paint a picture a day, usually of plants that could be found in his garden. I saw some of these paintings on my visit to Monreith House and I was very struck by them, as many of them, at the time when he was painting them, would have been plants and flowers that would have been very new to cultivation in Scotland.

“One of his pictures is of a beautiful pink flowering rhododendron, which was only introduced in 1901 from China. So he certainly would have been one of the first people to flower it in Scotland.”

Doing more research into Sir Maxwell’s gardening work, Baines was impressed by how much of a visionary the old knight was. Baines said: “He was a real pioneer of his time. During the later part of the 19th Century and the early part of the 20th Century, many plants were coming over from the far East, and some were successfully planted, while some were unsuccessful at taking root. Sir Herbert was trying out plants that had never grown on the British Isles before.

“One thing he did which was quite amazing, was that he planted over 200 monkey puzzle trees in a plantation in the middle of a field. You may occasionally see an avenue here or there of monkey puzzle trees, but to plant over 200 in a wood, was very pioneering. He may have been assessing their use as an economic forestry tree, we don’t know, but it is amazing to see.”

The exhibition showcases many of Sir Maxwell’s beautiful horticultural paintings, as well as photos, relics, and artefacts from Sir Maxwell’s Monreith House garden. Baines said that he thinks Sir Maxwell is a fascinating figure who should be better remembered in Scotland’s historic lore.

He explained: “We wanted to commemorate someone who we think should really gain national recognition. There are so many famous plant collectors, like the Williams of Caerhays down in Cornwall, and Herbert is really an unsung hero in that regard. We hardly hear about him.”

Sir Maxwell’s love for horticulture can be clearly seen in his stunning botany paintings, and he would often illustrate the many books he wrote on Scottish nature by himself. Baines explained what he found the most charming about Sir Maxwell’s paintings. “When you look at them, they are a mix between beautiful art which is pleasing to the eye, and scientific botanical pictures. It is almost as if they are a hybrid between the two. They are just so beautiful and colourful, and really catch the eye. He was an amazing man who was really talented,” he said.

A natural enthusiasm

Even back in the 19th Century, Sir Herbert Maxwell recognised the importance of looking after health of our wild creatures, big and small.

Maxwell was something of a jack of all trades, and the polymath often found ways to bring his passions together in extremely useful ways. A well connected descendent of one of Scotland’s oldest clans, he used this to his advantage to bring positive change to the Scottish environment that we can still appreciate today.

A keen angler and lover of nature, Maxwell recognised even back then the impact that over-fishing and over-hunting was having on local wildlife. Baines said: “He was probably one of the only ones, in a time when hunting, fishing and sportsmanship was extremely popular, to see that we could not keep taking from the world without giving anything back. He used his position in parliament to bring about closed season for salmon.

“People looked up to him. He was very influential and well connected, and I think his vast knowledge of so many different areas and his position as a politician meant that he could make things happen and change it for the better. The natural world was very close to his heart, and he wrote about 50 to 60 books, many of them on Scottish nature. His book on moths was seen very much as a bible on the subject at the time.

“He came from a line of Maxwells who all seemed to appreciate the natural world. The area around where they lived is very wild and untouched by man. It is right on the coast, and the environment that surrounded them is filled with amazing animals.”

The exhibition will run at Logan Botanic Gardens until April 30, with hopes to tour other regional gardens of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe