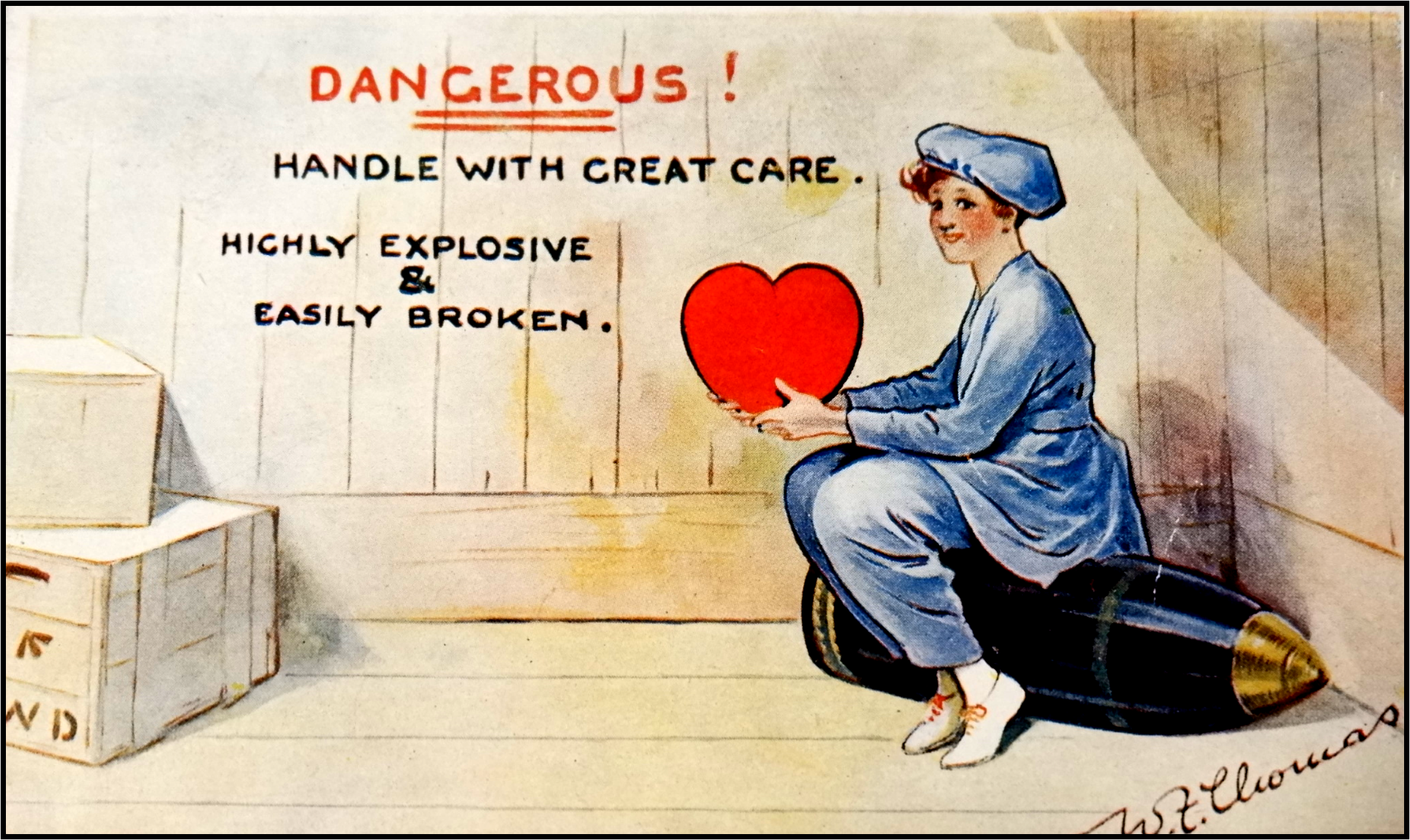

LOVE during wartime has never been potentially more explosive but passion still flared for workers thrown together at the world’s biggest munitions plant.

His Majesty’s Factory Gretna armed the British forces during First World War, with 30,000 workers coming from across the country to work in the countryside factory.

Some 12,000 were women and, just a few miles away from Gretna Green, romances blossomed.

Now, in the run-up to Valentine’s Day, a new exhibition called Love In Wartime has just opened at the popular Devil’s Porridge Museum in Eastriggs.

It tells the tale of the courtships, marriages and illicit liaisons of those thrown together amidst the global conflict.

“It really was a hotbed of romance,” said museum manager and exhibition curator Judith Hewitt.

“The majority of the girls were aged 17 to 20 and this was well-paid work, much more so than they would have earned in domestic service or working on the farm.

“They had more spare money than they’d otherwise have had and they lived in hostels, which was very different for them and with more freedom. It seems like a lot had a good time, with dances in Carlisle where they’d go drinking.”

The factory was built in just eight months, opening in 1916. The site was chosen because of its seclusion, which would minimise both casualties and word getting out in the event of an accident.

It made cordite – dubbed as looking like a devilish sort of porridge by Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle on a visit – the propellant for shells and bullets.

Within months of it opening, it produced more cordite than all the other factories in the UK put together.

It closed soon after the war but the site, still owned and used now by the Ministry of Defence, then became a major ammunitions storage facility as part of the Second World War effort. The exhibition, looking at the romantic connections there from both wars, has been put together from largely unseen material amassed over the past 30 years.

In that time, the Devil’s Porridge Museum has gone from a few display boards at the back of a church to a modern, purpose-built facility, attracting up to 20,000 visitors a year.

As well as the nights out in Carlisle, romances flourished at the cinemas set up in the two townships to house the workers, at Eastriggs and Gretna.

“The films they put on were viewed as somewhat dangerous,” said Judith. “The movies shown were the ones you’d have seen generally at cinemas, but there were complaints that they were provoking too many romantic feelings among the workforce.

“It was felt they should be showing patriotic films and not ones featuring liaisons. And there were concerns over darkened cinemas being the sort of places assignations could take place.”

But young lovers faced romantic obstacles in the shape of the ever-vigilant women’s police force.

At 150-strong, it was the largest such force in Britain. As well as being responsible for maintaining law and order, the factory’s morality also fell under their remit.

“They were mostly middle-class, middle-aged ladies,” said Judith. “They looked after the morals of the factory workers, checking the cinemas, stopping couples kissing on the railway platforms and preventing men or women getting into the same train carriages.

“And they patrolled the hostels to make sure there were no gentlemen callers. If someone got pregnant, they’d look into it and see if they could arrange a marriage.”

Eastriggs resident Sheila Ruddick, who is a secretary and trustee at the museum, knows all about how Cupid struck for those based at the site.

Her great aunt met and married there in the First World War and her mum wed her dad, who was based there, during Second World War.

“My great aunt Sarah worked at the acid plant,” said Sheila, 77. “She met a stonemason, one of the navvies, at the factory and they were wed in 1917 and moved to Stirling.

“They didn’t have a long life together, because I believe he died about 1925 and, after remarrying, she died when she was about 48.

“We’ve got an extract of their marriage certificate and a wedding photo but I didn’t know much about her and people didn’t talk about their time there.

“My grandmother Helen worked there as well, but she never spoke about working at the factory either.”

Sheila’s mum Jenny and dad Bob, who both lived locally, kept the family connection going. They wed in April 1940 and Bob, who saw active service in some of the war’s key battlefronts, latterly spent years patrolling the Eastrigg depot. Jenny’s wedding dress is one of the exhibits.

Judith hopes the new exhibition, launched last week, will paint a fascinating picture of love in a different time. And how the two sexes, in massive numbers and heightened circumstances, came together in a corner of Scotland so associated with romance.

“The marriage rate increased in both world wars,” added Judith. “In such urgent times, people had more of a live fast, die young mentality when you didn’t know if your lover was going to come back.

“There was a marry in haste, repent at leisure mentality in this environment where people were thrust together in this exceptional factory.

“Workplaces are still where a lot or romances happen and the First World War is the first time lots of women worked in male-dominated industries. So I suppose love was bound to blossom.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe