Glasgow portrait photographer aims to dispel stereotypes of fatherhood through new project

From the childlike Homer Simpson, to Mad Men’s distant Don Draper and Modern Family’s silly yet loveable Phil Dunphy, father figures are more often than not reduced to being fun, removed or useless.

Likewise, films like Daddy Day Care helped to immortalise the image of fathers as comically inept to look after children in the absence of their mothers.

But one Glasgow-based photographer is hoping to dispel these stereotypical cultural portrayals of fatherhood.

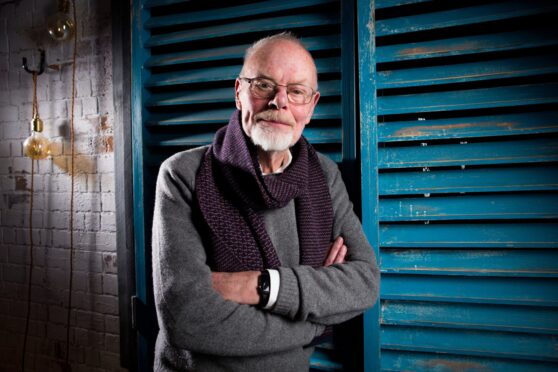

Dad of one, Eoin Carey, has been documenting fathers across Scotland in an attempt to challenge modern images of dads as “either heroes, incompetent or simply absent.”

Beginning as a result of his own experiences, Carey, 34, wanted to make a project based less on those typical vapid ideals of the dad joke or the dad dance but instead to show the reality of the tender and tired routines of everyday parenting.

“I wanted to make a body of work that documents fathers’ time with their children that gets away from stereotypes and instead shows a routine familiar to many, that is exhausting, mundane and stressful but also very beautiful, intimate and rich,” he said.

“Becoming a parent is an enormous life transition. I am really interested in this transition for fathers and secondary carers who do not go through a biological process and what it means for them.

“Motherhood is a concept that I feel is more nuanced and much more developed artistically so I wanted to put fathers in the frame in a more relatable and realistic way.”

With support from Creative Scotland, Carey photographed around 17 fathers and their children, and found numerous responses and outcomes across the board in terms of parenting, although there were also many similarities.

“I started with people I knew and fathers of children my daughter was playing with, and it was quite daunting because the hardest part of the project was actually getting fathers to be involved,” he said.

“There was a reluctance and a shyness because it’s obviously a very intimate thing for someone to come and join you in your house or come and meet you with a one year old or two year old when routine is so crucial.

“It was interesting though because I saw how differently fathers would parent – you know you just kind of assume that everyone does things the same as you or has the same values, but it is a completely different experience for everyone.

“But what I did see mostly was just this real portrayal of these fathers loving their children. And a real acknowledgement of that love too.

“You know there is often that stereotype that fathers are perhaps a little more reluctant to say those words but in every situation I photographed, that was something that really came across and almost took me aback, just how much these fathers loved and cared for their children.”

Far from documenting the nuclear family, Carey’s project also aimed to encompass the experience of fathers from a host of differing backgrounds.

“As the project grew and I was able to expand more, I wanted to show a greater diversity to make sure I was representing as many stories as I could,” he said.

“I met dads who were seeking asylum and I also met with a company in touch with prisoners who were fathers but unfortunately the coronavirus pandemic put a pin in that one.

“But I think it’s really important to steer away not just from father stereotypes, but also familial stereotypes of mum, dad, couple of kids, all living together too.”

He also found his own preconceptions challenged through the project and realised that fatherhood doesn’t simply cover those who associate as men.

“One of the dads involved with the project is actually a trans-woman who has been transitioning in the last number of years, so that was a huge education for me because I kept referring to the people in the project as the ‘men’ or the ‘lads.’ This of course isn’t the case.

“And because she has been a father to her children their whole life it’s not like she suddenly stops being a dad and becomes a mum, because the children already have a mum.

“So that was another level added – that fatherhood doesn’t actually even mean you have to be a man – she still encompasses all those caring, nurturing aspects and the more emotional side of it, despite her gender.”

Carey has a four-year-old daughter himself, and says being a father is one of the best things that has happened to him, a gift that is magic, but also one that can create loneliness in the early stages.

“In my experience and others I have met, early parenthood can be a very lonely experience for dads.

“The care that must be given as a parent can bring us in touch with a gentle, softer, loving parts of ourselves that men don’t necessarily get opportunities to experience regularly.

“But I love being a dad, and seeing the world through a child’s eyes is amazing – they re-teach us what is important.”

Discover more about the Father project and Eoin Carey’s work here.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe