If the walls could talk in one of Edinburgh’s finest town houses they would whisper about a scandalous duchess, the real-life murderer who inspired Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and the elopement of millionaire businessman Jimmy Goldsmith.

But the house is now giving up its secrets, thanks to John Fulton, who has gathered together the stories about the larger-than-life people who were connected with 66 Queen Street.

66: The House That Viewed The World (Scotland Street Press), describes the people and events of 14 people who crossed the threshold over 210 years, with characters ranging from heroes to villains, some of them famous – or infamous – and others revealed for the first time.

The author, a lawyer who spent 27 years working at the address for law firm Tods Murray, traces the origins of the house to a stonemason who went on to build The White House – and he has now been invited to Washington DC to launch his book.

“I wasn’t aware of most of these stories while I was working there until I researched the National Archives of Scotland,” said Mr Fulton. What he found holds up a mirror to Scottish society throughout the last two centuries, but also highlights how little has changed.

Two cases handled by the law firm, which owned the premises for 150 years, particularly foreshadow modern-day events: the notorious divorce case of Margaret, Duchess of Argyll, the first woman to be “slut-shamed”; and one man’s battle over his gender identity.

“I went into the research with an open mind and tried to let the characters tell their own stories to allow readers to make up their own minds,” said Mr Fulton.

Here, we reveal some of the compelling stories told in the book.

The playboy & the heiress

In 1953, Bolivian Atenor Patino, one of the world’s wealthiest men, forbade 21-year-old James Goldsmith from seeing his 18-year-old daughter, tin heiress Isabel.

The headstrong young man, with a reputation as a playboy and gambler, refused and the young couple eloped to Scotland where they could legally be married.

The runaway lovers embarked on a cat-and-mouse chase, pursued by the world’s press and Isabel’s furious parents, who sought legal advice from David Scott Moncrieff, a partner in Tods Murray & Jamieson.

James and Isabel toured the Highlands before finishing holed up at Prestonfield House. After the owner helped them escape in the back of the van he used to ferry pigs to market, they were married at a registry office in Kelso. Five months later, pregnant Isabel suffered a massive cerebral haemorrhage. The baby survived, but she did not.

“It was like a cross between John Buchan’s 39 Steps and an Ealing comedy,” said Mr Fulton. “It was funny but in the end poignant as tragedy snatched his young bride from him.”

Billionaire Goldsmith died in 1997 aged 64, leaving behind three families, seven homes, eight children, wife Lady Annabel, and a mistress.

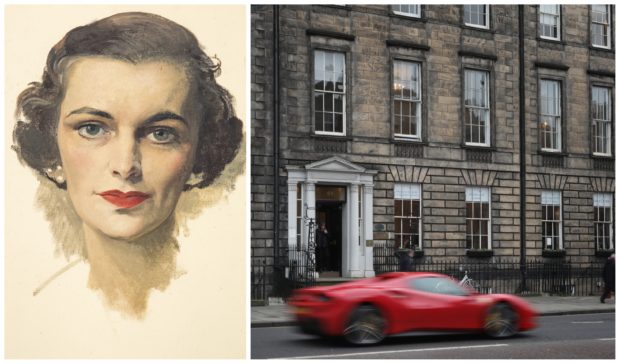

The duchess & the judge

In 1963, the divorce case in Edinburgh’s Court of Session brought by the Duke of Argyll against Margaret, Duchess of Argyll scandalised the nation with lurid details that included pornographic Polaroids of the Duchess and a mystery “headless man” who has never been identified.

The Judge, Lord Wheatley, said the photographs “revealed that the defender was a highly-sexed woman who had ceased to be satisfied with normal relations and had started to indulge what I can only describe as disgusting sexual activities to gratify a basic sexual appetite.”

Also introduced to the court was a list of as many as 88 men with whom the Duke believed his wife had consorted; the list is said to include two government ministers and three members of the British royal family.

Solicitor Jack Macfie, a partner in Tods Murray & Jamieson, represented Margaret in what was then the longest divorce case in British legal history.

“Society was unfair to women and the judge was pretty harsh. She suffered from double standards as she was given a harder time than she merited,” said Mr Fulton.

“There are reasons she behaved as she did: her wealthy parents always had ambitions for her and marriage to the Duke was more like a business agreement.”

The doctor & the inheritance

A man’s gender was challenged in court when he inherited a baronetcy.

Born Elizabeth, the youngest daughter of the 18th Lord Sempill on September 6, 1912, doctors were unsure of the baby’s gender and asked the mother to assign it.

Bettie grew up a tomboy on the family’s estates at Craigievar and Fintray in Aberdeenshire.

From 1945 Bettie worked as a doctor in Alford and led life as a man before legally changing gender and name. As Dr Ewan Forbes-Sempill, he married the practice receptionist, Patty, in 1952.

The respected GP said: “It has been a ghastly mistake. I was carelessly registered as a girl in the first place.

“I have been sacrificed to prudery and the horror which our parents had about sex.”

When his brother died in 1965 without an heir, his cousin John challenged his succession in court, arguing that the re-registration was invalid. John’s agents, Tods Murray & Jamieson, took the case to the Court of Session, which found in favour of Ewan.

Controversially, the case was heard in private at 66 Queen Street, so the press were unable to get a whiff of the story.

John’s lawyers appealed against the ruling to the then-Home Secretary, James Callaghan, who in 1968 directed that the name Sir Ewan Forbes of Craigievar be entered in the Roll of Baronets.

The killer & the inspiration

In 1878 the jury at the High Court in Edinburgh found Eugene Chantrelle guilty of murdering his wife.

Watching the proceedings was 27-year-old Robert Louis Stevenson, who was friends with the advocate in the case, Andrew Murray, the son of a partner at Tods Murray & Jamieson, as the law firm was then called.

The writer was fascinated by the dual nature of the defendant, a Frenchman whom he’d met and who had struck him as an educated, talented man but whose dark alter ego was revealed during the trial. Chantrelle was a 34-year-old French teacher when he seduced 15-year-old Elizabeth Dryer. Her family forced him to marry her after she fell pregnant but he abused his wife and frequented brothels, before poisoning her by lacing an orange with opium. He insisted on his innocence all the way to the gallows.

Stevenson wrote in his diaries: “Chantrelle bore upon his brow the most open marks of criminality; or rather, I should say so if I had not met a man who was his exact counterpart in looks, and who was yet, by all that I could learn of him, a model of kindness and good conduct.”

Eight years after the trial, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was published.

The stonemason & The White House

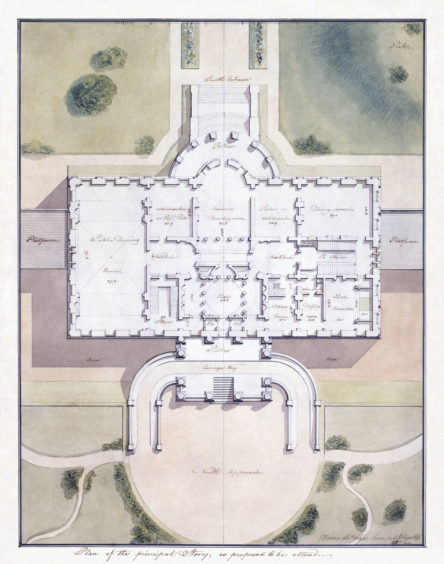

John Williamson was an Edinburgh stonemason who worked on the New Town, including 66 Queen Street, a three-storey townhouse completed in 1791.

“Meanwhile, work had begun on a new building on a new continent, which is now one of the most iconic in the world,” said Mr Fulton.

The committee behind the construction of a presidential mansion in Washington hired John Williamson and his team of stonemasons in 1794.

He was responsible for the naming of The White House as he covered the porous sandstone in thick whitewash to protect it from the weather, as was the custom in Scotland.

This dramatically changed the mansion’s appearance and locals began to call it The White House – a name President Theodore made official in 1901.

66 The House That Viewed The World by John D.O. Fulton is published by Scotland Street Press and is out now.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Shutterstock

© Shutterstock