CONSIDERED by many as Scotland’s chief art form, poetry has been an outlet for expression for centuries.

Biting, sharp and personal, it can embody the life and passions of its writer – whether it be a Robert Burns, a Liz Lochhead or a Jackie Kay – in a way many other art forms cannot.

In a world where people are looking for new ways to make their voice heard, a form known as slam poetry has emerged as the latest platform for such expression and events are becoming more and more popular across the country.

Slam poetry is, essentially, a competition in which poets perform their work in front of an audience, who are also the judges.

As well as their words, the way in which the performer delivers their work is considered.

While competitive by definition, a community of creatives across Scotland has been fostered in which performers are given encouragement by their peers and newcomers are openly welcomed.

The slam poetry format, credited with revitalising interest in poetry over the past few decades, originates from the late 1980s in Chicago, spreading quickly to New York and worldwide.

Particularly popular with young poets, it been seen as an outlet for expression and discussion of topics of identity and politics, race, economy and gender.

Indeed, many performers find it easier to approach some subjects or share an experience in the form of performance poetry, rather than in an everyday conversation.

“Slam poetry is just the latest version of Scotland’s centuries-old love of public poetry that is feisty, satirical and personal,” Beth Cochrane, Scottish Poetry Library’s events coordinator, explains.

“It’s very direct, conversational even – there’s no mediation through plot or characterisation.

“As a result, the scene both within Scotland and outside has grown to pride itself on its openness to hosting diverse voices, which in turn has spurred the popularity of both spoken word nights and the books that have been published by poets who have emerged from that scene.”

Like punk, Beth says, the spoken word scene has a strong DIY ethic and its rise in recent years can be partially attributed to two developments.

One is the current economic climate, where many young people feel let down by an economy that struggles to provide jobs and a sustainable income.

“Unlike most other art forms, poetry doesn’t need anything to be created and find an audience,” Beth says. “It doesn’t need a camera, editing equipment; it doesn’t need guitars or drums; it doesn’t even need pen and paper – it just requires a voice.”

The modern way of life, where technology is central to everyday living, has also provided the perfect platform for poetry.

Beth adds: “Poetry is very well suited to the current digital age. You can get a real sense of a poem from a few lines in a tweet.

“Slam poets can film themselves and upload that poem to Facebook or YouTube and, if it strikes a chord, can go viral.

“A novel can’t do that, a play can’t do that, but a poem can.”

Technology has also made organising and publicising spoken word nights so much easier.

The Scottish Poetry Library has hosted a number of these events as part of their commitment to supporting the medium in all of its forms.

And many too have sprung up in university unions across the country, welcoming students and those outwith the campus to take part, whether they’re on stage or just taking it all in.

Why slam?

Aloud, based out of the University of Glasgow, hosted regular slam poetry events across 2018, with many more planned for 2019.

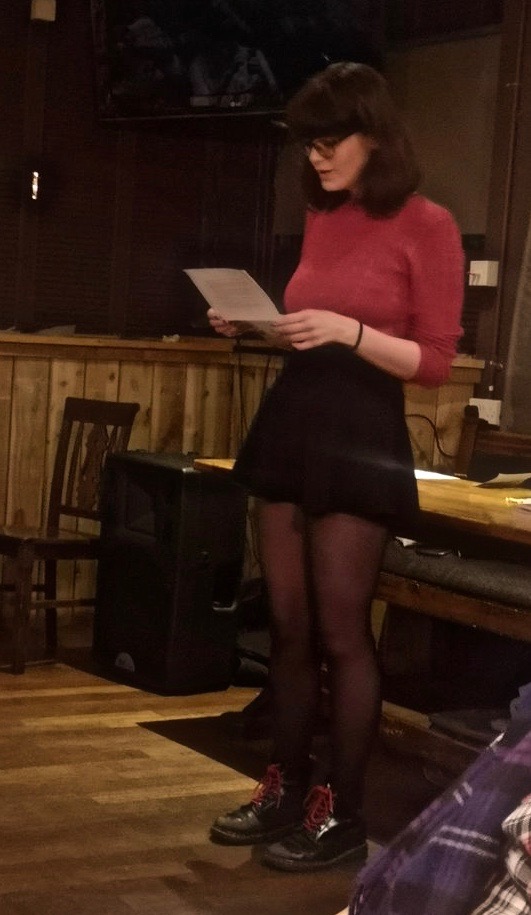

We spoke to the performers who were voted the top three on the night at a recent poetry slam held in Glasgow University’s Queen Margaret Union to find out what they love about spoken word and how they got into slam poetry.

Gray Crosbie, 27, school support assistant

How did you get into spoken word performances?

I’ve always loved writing. I started out writing prose, mostly tiny flash-fiction pieces, then moved on to writing poetry too. But I was a really anxious kid, so it’s been a long journey to build up the confidence to step on a stage and share my writing.

Just a few years ago, I never would have imagined I’d be brave enough to do this, never mind completely love and be addicted to doing so. But getting into performance poetry is definitely one of the best things I’ve ever done.

What do you enjoy the most about slam poetry?

For sure one of the best things is being part of the incredibly friendly and supportive spoken word community we have in Scotland. It’s such a diverse and inclusive community too.

Writing can be a pretty lonely pursuit, but open-mic nights and slams give you a chance to share your work and get feedback, as well as hear what other poets are up to. I’ve met so many lovely and talented folk through performance poetry.

Why do you think slam poetry is such a powerful medium for storytelling and allowing people to express themselves?

I think one of the amazing things about poetry is that it can help you discuss experiences and issues that you might not be able to talk directly about in a conversation. Sometimes I stand on a stage in front of a crowd and share some pretty personal things, things I wouldn’t be able to sit down and talk to the people I’m closest to about.

I’ve actually used poetry performances to “come out” to some of my family. I also often find just writing a poem can be a great way of exploring and processing thoughts and feelings that you might otherwise not delve into. Poetry’s a great therapy!

What advice would you give to people wanting to get into performance poetry?

Go for it! It can seem scary but there are so many wonderful, supportive people out there. You could start by going to a few open mic nights, just to have a listen even and find one you feel comfortable at. And there’s such a huge variety of different poetry nights in Scotland. The God Damn Debut Slam in Edinburgh is a brilliant “beginner” slam. It’s an incredibly friendly and supportive night that’s also just really great fun.

Ben Rogers, 28, restaurant worker and creative writing student

How did you get into spoken word performances?

I actually wanted to be a rapper when I was young and then realised that it was the words that I was interested in, so I started writing poems because of that. I went along to one of the open mic nights with my friends and gave it a go, immediately falling in love with it.

What do you enjoy the most about slam poetry?

It’s great to see people express themselves in a creative way, you always get a wide variety of subject matter which is nice.

The camaraderie between the poets is also a plus, everyone is welcoming and open to meeting new people and encourage everyone

Why do you think slam poetry is such a powerful medium for storytelling and allowing people to express themselves?

I think that it’s because of the open environment that the medium exists, people are actively encouraged to express themselves in a creative way and are pushed on by each other.

What advice would you give to people wanting to get into performance poetry?

Do it, you won’t regret it. Everyone involved wants more people to give it a go and will be more than happy to help and encourage you.

Lydia Roy, 20, Literature / History student

How did you get into spoken word performances?

I got into spoken word proper through Aloud, back in first year of university (I was a teenager thrown into a new situation and studying literature, of course I was going to take up poetry).

Aloud was the first time I had experienced poetry in a creative space that wasn’t strictly academic, and I was struck (hard) by how free/genuine/interesting the people performing there were.

I went along for nearly a year, soaking it all up, until I gave it a shot myself and got hooked. (Slam competitions, on the other hand, are still quite new to me so I can’t speak much on that!)

What do you enjoy the most about slam poetry?

The thing that I enjoy most about slam poetry is actually what sets it apart (in my head, it’s a bit of a problematic demarcation) from written poetry: the relationship that you can set up onstage between yourself and your audience, trying to measure their reactions and emotions and fit yourself around them.

It’s like a really intense conversation taking place on a much larger scale, and you get to sort of tailor your voice/presence to the atmosphere in the room. It’s a very cool feeling.

Why do you think slam poetry is such a powerful medium for storytelling and allowing people to express themselves?

I think that slam poetry has a unique ability to allow both the poet and (sometimes, if it works!) the audience an emotional catharsis-type-experience without forcing them to relive any actual trauma directly; within that performative context you can perform experiences in an abstracted way and from odd angles.

You get to play around with meanings and implications, and create something different every time.

What advice would you give to people wanting to get into performance poetry?

I don’t know if any advice I give would be at all useful! But I will say that, for young poets especially, there can be this slight pressure to make yourself extremely vulnerable onstage and—though I think that vulnerability can be powerful and important when used properly—I don’t think that you necessarily have to pour your guts/soul/viscera out to every audience, every time. Knowing your own boundaries is important.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe