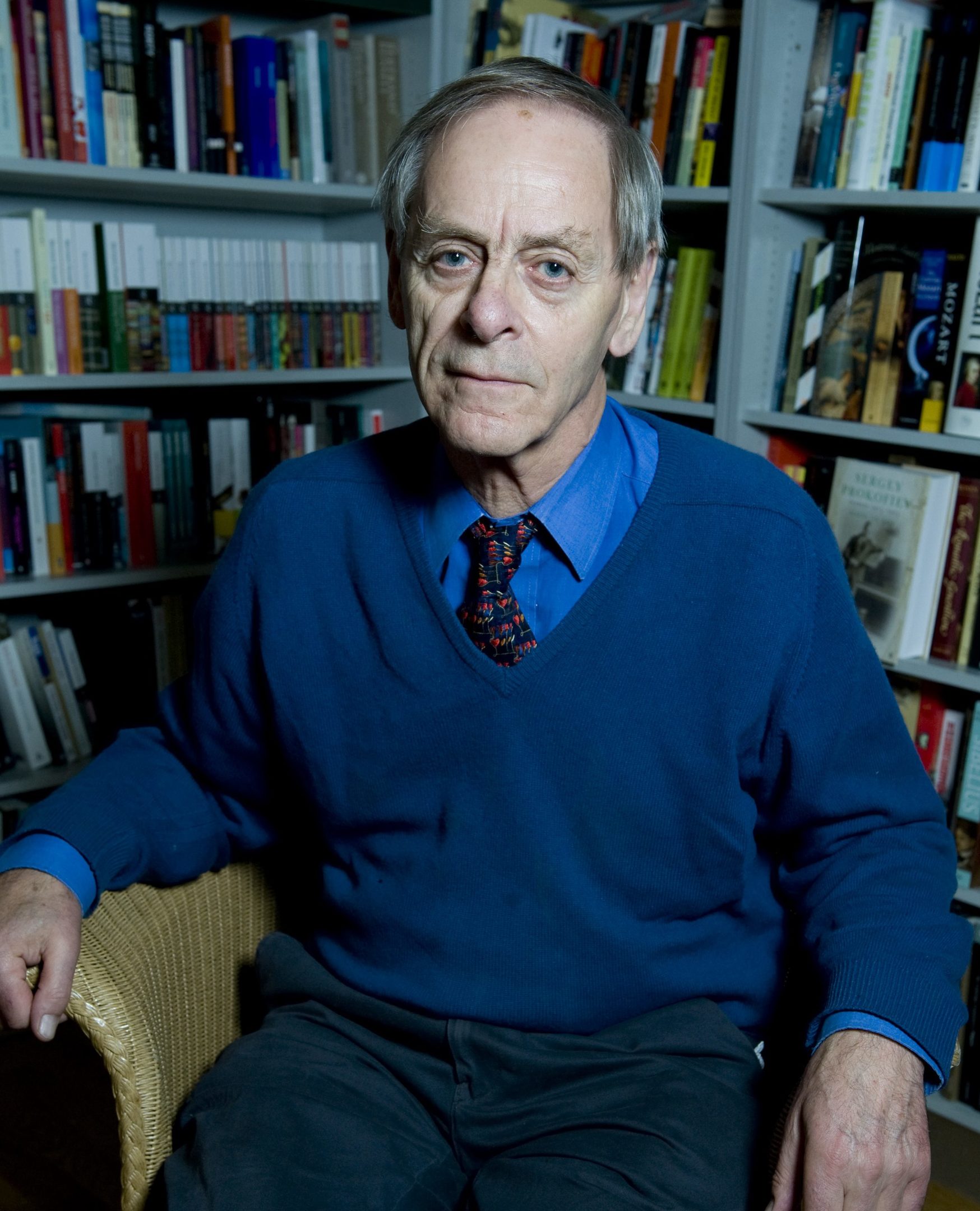

ACCLAIMED author and journalist Neal Ascherson helped launch the Bus Party in 1997 when writers, artists and musicians toured the country campaigning for a Yes vote in the devolution referendum.

Here are his memories of that period.

IT was midnight, at the top of the Drumochter Pass.

We stopped the minibus and climbed out into the darkness, scented with invisible heather and bog myrtle, to look up at the sky.

It was uncannily clear, the Milky Way lying like a silver fleece across the northwest.

As we stared, a brilliant meteor flashed out of the constellations and slid towards the Pole.

We sensed a good omen.

The Bus Party was making an overnight run from Inverness to our next date at Biggar in the early morning.

But this was no conventional effort.

We were a travelling conversation and ceilidh, haring round the land to listen and learn as well as to speak and entertain.

Why? The menace of dire, routine Scottish campaigning had begun to emerge.

The same old faces were preparing to squabble about the same old petty conundrums – the people would watch with gloomy scepticism as the politicians rattled on about the tartan tax, the West Lothian Question, local government sleaze and the business rate.

There was a danger Scots would be so alienated by this debate they wouldn’t vote, or return a lukewarm, indecisive verdict that – as in 1979 – devolution would be stillborn.

So the Bus Party was dreamed up.

An old man in Inverness said: “Never again will this chance come. Your fathers and grandfathers look down at you”, and I heard indrawn breath all around me.

“Let politics look after itself – this is a moral and a spiritual decision”, and the sober citizenry broke into applause.

But there was fun, too. There was the Arbroath schoolboy who said: “I want the parliament to help wee-bitty Third World companies to compete wi’ multinationals. And mair flags!”

There was the couple from the Home Counties visiting Forres: “Good luck to you. But mind you don’t get a rotten government like we’ve had in England for the last 20 years!”

There was the man in Aberdeen’s St Machar’s Cathedral who shouted: “Comparing Scots to sheep is an insult to sheep. Sheep don’t have the vote, and if they did they wouldn’t vote for mutton pie!”

A girl from Biggar told me: “I don’t feel put down because I’m Scottish. The English and the Scots put each other down in a perfectly normal way.”

We met English families from the RAF base at Kinloss who were happily preparing to vote ‘Yes’.

At midnight on the Wednesday before the vote, we returned to our starting-place, Calton Hill in Edinburgh, where the empty parliament building waited.

The Vigil veterans, who had squatted at the gate for 1979 days to demand a Scottish Parliament, greeted us.

Then William McIlvanney recited the ancient lament for King Alexander III, one of this small country’s many lost leaders: “Succour Scotland and remede/That stayed is in perplexitie”.

And quietly, without trumpets, Referendum Day began.

The music of that 1997 referendum took a long time to die down.

A few months later, when Parliament was meeting, I saw Will Storrar (our Bus Party captain) in the gallery near me. MSPs were droning on about motions and amendments as if they had been doing it all their lives.

I caught Will’s eye, and we shook hands long and tightly. We did it! We did it !

Has Parliament lived up to what we hoped ? Not quite.

We wanted the opposite of Westminster: a place where the elected members cooperated rather than confronted.

In the powerful committees, MSPs often forget to be party enemies.

But First Minister’s Questions can be silly, un-Scottish charades of pumped-up rudeness.

Parliament must be open to all, inviting all citizens to participate in lawmaking.

I’d like to see the First Minister make an annual state-of-democracy speech, to report on progress towards those four goals.

My verdict on the first 20 years – good, but must do much better.

I was feeding my daughter when the result came in and the tears just rolled down my cheeks

Susan Deacon, former Labour MSP and health secretary, remembers the campaign.

I SPENT much of the 1990s, mainly within Labour, helping build the case for a Scottish Parliament and then when it came to 1997, I was pregnant.

I will always remember the moment when the result came through – I was feeding my daughter Claire in front of the TV in the early hours and the tears just rolled down my cheeks.

I’d had chances to stand for Westminster but the Scottish Parliament and devolution was all I was interested in, so it was wonderful and I was so proud to be a part of the first government.

If I have one disappointment it’s that we have not been able to shake off the tribal nature that dominates Holyrood.

We haven’t been able to get genuine cross-party working and the lack of truly independent list MSPs – not aligned to parties – is also bad for the health of the place.

As each day went on, I became more convinced it was going to be a resounding win on both questions

John Swinney was SNP MP for Tayside North.

MY feeling about the campaign was that it struggled to get going.

The folk that were behind the campaign just couldn’t get it at anything like an exciting threshold.

I would say the public woke up to the campaign on the Sunday before polling day.

We had Sean Connery and high profile events in Edinburgh. I spent the final few days energetically campaigning and, as each day went on, I became more convinced it was going to be a convincing win on both questions.

The night itself was one of those nights where when I saw the opening of the first box I knew how decisive it was going to be.

We had a fight on our hands and the first ballot box said to me that if we were this far ahead in North Tayside then we were going to win hands down.

The parliament is where people look to make things happen and change things.

It is where people vent their frustrations and, increasingly, it is where people look to for their hope.

I think Scotland became partly independent in 1997, more independent after the Scotland Act of 2012, more independent with the Smith Commission.

It has not become independent, but it is significantly more independent than it was 20 years ago.

None of the campaigners contemplated that the parliament would lead to worse education for kids

Nigel Smith was chairman of the Yes campaign in the 1997 referendum.

The Scottish Parliament has been only a partial success, certainly less successful than we campaigners hoped for at the outset in 1997.

It can do better.

After 20 years across three different parties, five parliaments and seven First Ministers, criticism can no longer be confined to the current and past governments but must extend to the Scottish Parliament as a whole.

Many areas of Scottish public life, probably numbered in hundreds, have felt the benefit of policy properly taking into account circumstances specific to Scotland, from marine conservation to mental health.

But none of the campaigners in 1997 remotely contemplated the possibility that the Scottish Parliament would lead to relatively worse education for the generation of children born in 1997 and since.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe