He is a caring “Opa” or grandpa; a man she looks up to, and with whom she has played, laughed and mourned.

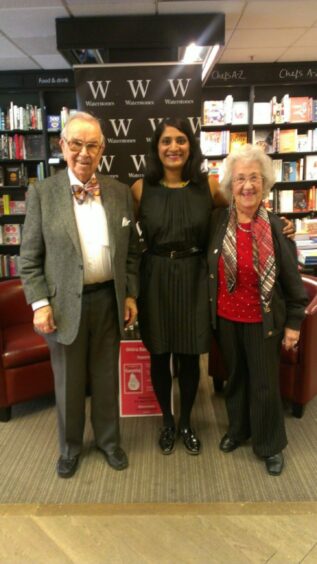

But Chitra Ramaswamy, 43, and Henry Wuga, 98, are not related. Theirs is a remarkable friendship forged in later life that bridges difference in age, gender, religion and culture. And it is one that has blossomed into a bond so strong, it is now the subject of a book.

Ramaswamy first met Wuga 11 years ago in Glasgow through her work. Neither could have imagined how profoundly that first meeting would change their lives.

Wuga, a retired kosher caterer, is a Holocaust survivor who escaped Nazi persecution in Germany on a Kindertransport when he was 15. Ramaswamy, half his age, is the daughter of Indian immigrants, who grew up in London’s leafy Richmond before moving north to graduate from Glasgow University, going on to become an award-winning author and journalist, broadcaster, and food critic. On the face of it, they are poles apart.

“You might see Henry and I walk down the street together and think, ‘what on earth is the story of that?’” laughs Ramaswamy, “but actually, we are really quite similar.”

Speaking from the home in Edinburgh she shares with Claire, her partner of 18 years, their two children aged eight and four, and the family’s pet dog, she adds: “Henry was a chef. He and his late wife Ingrid ran the biggest kosher catering company in Glasgow. And I’m a journalist and restaurant critic. We always talk about food and eat food – it’s a shared love of ours.

“We both feel ourselves as being Glaswegians and we love Glasgow. The things we care about are the same. We are both single-minded and value kindness, humanity, telling the truth and standing alongside people who are fighting for what is right. We are motivated by justice.”

It’s a friendship that began with a first, formal meeting at the elegant home Henry – then an octogenarian with a “penchant for bow ties, opera and skiing” – shared in Glasgow’s Giffnock with his wife Ingrid. Ramaswamy was there as a journalist to interview the Wugas on their wartime experiences.

Smiling, the author tells P.S.: “The seeds were sewn on the very first day. I spent the afternoon in the company of this very dignified German-Jewish refugee couple, and I was amazed by the warmth they generated when speaking about such unconscionable atrocities. They seemed so in love with life. I found that completely intoxicating and genuinely inspiring.”

She recalled that day later in her article: “Henry invited me back to Giffnock for lunch. Poached salmon, boiled eggs in marie rose sauce, warm bread rolls, cheeses and homemade cake. Delicious. That lunch turned into many more, and one day Henry asked if I was married. ‘No,’ I tentatively said. ‘But I’m in a civil partnership. With a woman. I’m bisexual.’ ‘Ah,’ he replied without skipping a beat, ‘next time you must bring her.’ And so I did.”

Five days after the birth of their son, the writer and her partner bought their baby to meet the Wugas.

Ramaswamy says: “It was probably around that time I started referring to them as my adopted Jewish grandparents. And Henry always signs birthday cards to the children Opa, which is the German word for grandpa.”

A few years later, when she gave birth to the couple’s daughter, she vividly recalls her newborn “awakening something deep and instinctual” in Ingrid who by then, at 94, was suffering from vascular dementia.

The two families went on to enjoy cultural outings together – the Edinburgh International Festival and concerts, birthday parties and more lunches. “Our families have, in that slow way that friendships are formed, become close,” adds Ramaswamy. “There is something about our values and our outlook on the world that are similar, the things that we care about.”

Henry is a Holocaust educator who, in his 70s, 80s and 90s, has visited hundreds of schools and university campuses in Germany and Scotland, talking about his life so that we can learn the lessons from the darkest days of our shared past.

With her book Homelands: The History Of A Friendship, billed as an exploration of belonging, prejudice and family, Ramaswamy wanted to help enshrine and protect his precious memories for generations to come.

The book traces how the young Henry witnessed the nightmarish spectacle of the Nuremberg rallies, the torch-lit parades marching “15 abreast” down his street. And it tells how his Austrian father and Jewish mother, in May 1939, managed to secure him a place on the Kindertransport; the British rescue effort that saved the lives of almost 10,000 predominantly Jewish children in the months leading up to the Second World War.

The book goes on to follow the young refugee to Glasgow and reveals how, like many other Jewish refugees, he was interned during the war and detained in six camps, including the high security camp Peveril on the Isle of Man, before his final release aged 16. He met his bride-to-be, who had also escaped on the Kindertransport, in 1941 at a refugee base in Glasgow’s Sauchiehall Street. And, while he never saw his father again – he died in 1944 from a heart attack – Henry was later reunited with his mother, who had courageously written constantly to him from the ruins of Nuremberg.

Ramaswamy says of Henry: “His story is amazing. He is the German-Jewish refugee who was born into 1920s Nuremberg, which by the 1930s was the most anti-Semitic place on earth.

“I really wanted to follow the whole story of his life. I knew that would mean this book would criss-cross over a century of history, both his and my own. It felt like an enormous undertaking and a big responsibility, because he is of that generation that we now refer to as the last generation of eye witnesses to The Holocaust. Although Henry left Germany on the Kindertransport in the spring of 1939, he was there right through the 1930s.

“He saw the night that the Nazis call Kristallnacht (when Nazis torched synagogues, vandalised homes and killed Jews). So many of his generation take it upon themselves to speak and tell their stories. But they are reaching the end of their lives at precisely the moment Holocaust denial is on the increase along with the rise of white supremacy, the far right, nationalism and popularism. So we need to pay attention more than ever before.”

With Europe teetering on the brink of a Third World War, Ramaswamy says her friend’s story is more relevant than when she first sat down to write the book. She says the UK’s vote in 2016 to leave the European Union – which was set up to integrate member states politically and economically – was “personal and devastating” for the Wugas.

The writer explains: “Henry has said that he sees very striking parallels with the 1930s Nuremberg that he grew up in, where slowly and incrementally, enormous changes meant that he was no longer a citizen of his own country and could no longer remain there with his parents, although he was still a child. He is appalled that he has had to see that again in his lifetime.”

Homelands was written during the Covid-19 pandemic in a climate of agonising grief for Ramaswamy and Henry Wuga. On June 3, 2020, during the first lockdown, her cherished 76-year-old mother Shylaja, a retired doctor, lost her battle with breast cancer. At the time, Henry wrote to his young friend: “Be brave,” and signed-off, “we send our love – your adopted grandparents.” Four months later Ingrid died too.

In many ways writing the book helped Ramaswamy through those painful first months. She recalls: “There were certain parts that helped me to grieve my mum’s death. I was working on getting Henry’s mother’s letters translated and I immersed myself in the fortitude and the bravery of this exceptional woman Lore Wuga and her single-minded vision of getting to Glasgow to be with her son, they really helped me. She helped me, this woman I had never met.”

Ramaswamy and Wuga’s friendship is testament to the unbreakable bonds that can be forged across gulfs in age and culture and a reminder that, ultimately, we are all on the same journey.

Ramaswamy, whose previous work Expecting: The Inner Life Of Pregnancy won the Saltire First Book of the Year Award, says: “I didn’t want to compare my experiences to that of a German-Jewish refugee who fled the Holocaust. Obviously, our histories have nothing in common. It was about how we could make our friendship speak through our stories and make our stories speak to one another in a way that is true and a vital.

“For all that, it is about some of the great tragedies of the last century and, indeed, this one. It is an incredibly hopeful book about love and family and kindness and making people feel welcome. A kind of hospitality Henry and Ingrid represent and embody. I am increasingly realising that the story of this book is not about our difference but how similar we are.”

Chitra Ramaswamy is at Borders Book Festival, Melrose, on Saturday, June 18. Visit bordersbookfestival.org

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe