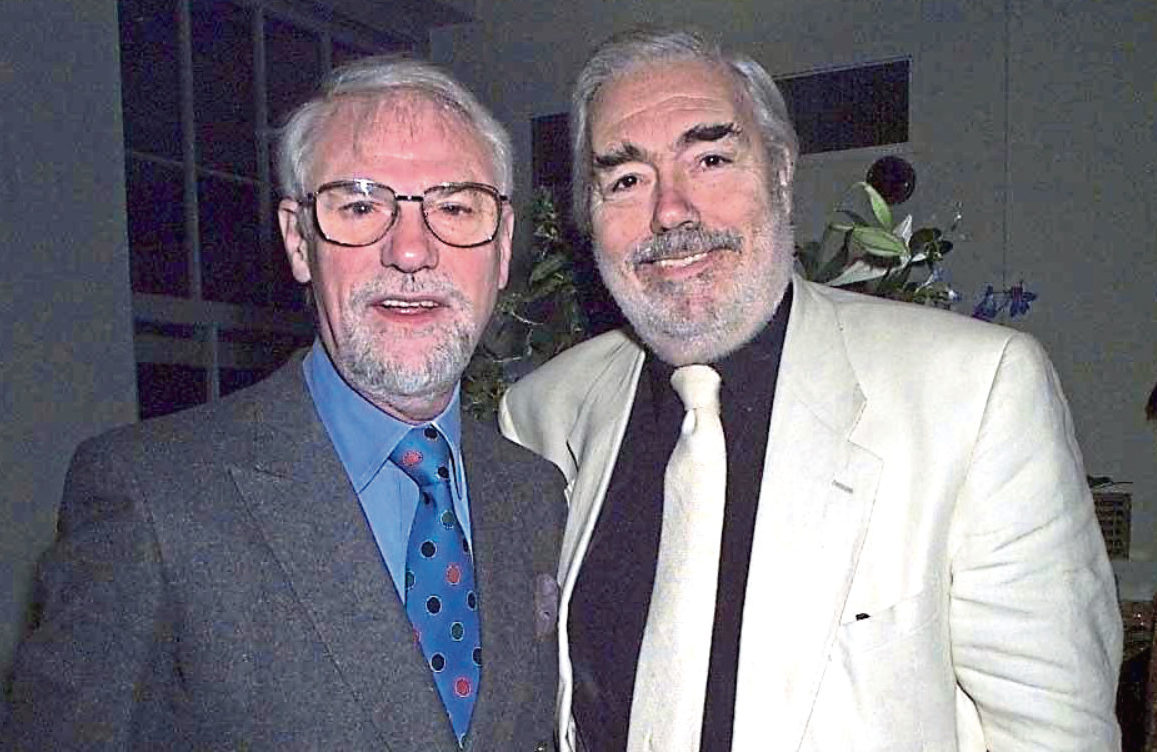

Writing partnerships are born in a whole manner of ways but none can match the unusual circumstances in which Ray Galton and Alan Simpson’s came into being during the late 1940s.

Both were patients at Milford Sanatorium, a TB hospital, set amid the Surrey countryside.

When a 16-year-old Galton was admitted to Milford in January 1947, his chances of survival were so low that he was given just two weeks to live.

He was working in the head offices of the Transport and General Workers’ Union in London when rushed to the sanatorium.

Fortunately, Galton was strong enough to beat the infectious disease. Aged 20 when he finally left Milford, he’d endured three and a half years at the hospital.

Galton had been at Milford just over a year when an 18-year-old Alan Simpson arrived. He’d been working as a shipping clerk in London when the disease struck.

When I chatted to Ray Galton, who died in 2018, aged 88, he clearly remembered the day Simpson arrived. “Up until that time, the place was full of mainly ex-servicemen.

“I was the youngest so when Alan arrived, together with other young guys, the atmosphere changed immediately.”

It soon became apparent that they shared much in common.

“We were both comedy fans, liked films and had the same taste in music – in fact, it’s amazing how close our thoughts were regarding politics, culture, wine and food,” explained Simpson, who died in 2017, aged 87.

“More importantly, our sense of humour was almost identical,” added Galton. “This meant that as soon as we started working together we became, almost, telepathic. We could finish off each other’s sentences.”

The seeds of their working partnership were sown at Milford. The hospital possessed its own radio system and, initially, Radio Milford broadcast for an hour a day, playing record requests from a converted linen cupboard.

“Later, we tried our own version of BBC panel games, like Twenty Questions, and then Alan and I dreamt up an idea for a comedy series titled Have You Ever Wondered?. We agreed to write six 15-minute instalments but ran out of ideas after four. But that was the start of our partnership.”

Galton and Simpson enjoyed writing comedy sketches so much that they set about realising their dream of becoming professional scriptwriters upon leaving the sanatorium.

Initially, they penned a sketch and posted it to Gale Pedrick, who assessed unsolicited scripts at the BBC.

To Galton and Simpson’s delight, Pedrick was so impressed that he invited the writers to the BBC for an informal interview.

Later, the sketch was circulated amongst BBC producers, including Roy Speer, who was producing Happy-Go-Lucky, a comedy vehicle for Derek Roy.

Roy himself got to see Galton and Simpson’s sketch and snapped it up as well as any one-liners they could write for his show, paying five shillings a time.

By the end of the series, they were writing full-length scripts, including the last three shows, had met Tony Hancock, who’d play a crucial role in their careers, and become full-time writers.

By now, Galton and Simpson’s names were known by the BBC hierarchy and they were asked to write the last six instalments of Calling All Forces, an hour-long sketch show co-compered by Tony Hancock and Charlie Chester, and – later – Forces All-Star Bill, again with Hancock.

Before long they’d swapped the lounge of Alan Simpson’s mother’s house for their own office, even if the location, above a fruit and veg shop in Shepherd’s Bush, wasn’t the most salubrious setting in London.

Other work followed but Hancock’s Half Hour was their first big hit. In bringing this popular series to life, Galton and Simpson became trailblazers in the world of comedy.

For years, whenever the British public wanted a little light relief from the mundanities of life, they tuned in to the radio and were entertained by the traditional variety show, where sketches were punctuated with musical turns.

Galton and Simpson, however, headed in a different direction.

Instead of a series of sketches, they placed their characters in a half-hour uninterrupted storyline – situation comedy, of which Galton and Simpson were early pioneers.

They wanted the humour to emanate from the character or the storyline rather than relying for laughter on jokes.

Hancock’s Half Hour began on radio with a cast including Kenneth Williams, Sid James, Bill Kerr, Hattie Jacques and Moira Lister. But the star of the show was undoubtedly Hancock.

“He was an instinctive comedian and out of that comes timing. You never had to worry about Tony timing a laugh – it’s not every comedian who can do that,” said Galton.

“We rarely had to explain anything to him regarding the script – except, perhaps, the odd Cockney phrase,” added Simpson.

On Saturday October 30 1954, a handful of actors dodged the autumn showers and made their way to London’s Camden Theatre, ready for the 10am rehearsal for the opening episode of Hancock’s Half Hour. Before the day was out, they had helped lay the foundations for a radio show that would become a British institution.

Six series were broadcast between 1954-59, by which time the show had already transferred to TV. On the small screen, seven series were screened between 1956-61.

On TV, the format changed with Tony Hancock and, initially, Sid James playing the main roles.

Reflecting on the first day of rehearsal for the opening TV episode, Alan Simpson stated: “I liked going along, although Ray used to get very nervous. He’d be convinced everything would be a disaster, so I’d have to reassure him.”

Actors use different methods to learn lines but some find it more taxing than others.

Whereas the experience Sid James picked up in the film world helped when it came to learning scripts, Hancock struggled, as Galton recalled: “It didn’t come naturally to Tony. I think it took quite a toll on him.”

Later in the series, Hancock relied on cue cards, set off camera, to show him his lines.

Hancock was also nervous before recording began, as Alan Simpson explained.

“You wouldn’t go near him for half an hour before the show started and could hear him in his dressing room dry heaving. But as soon as the show began he was fine. Hancock was very professional in those days and never had a drink until after the recording.”

For the final TV series, Hancock requested changes to the show’s format and the dropping of popular sidekick Sid James – a decision which devastated the veteran actor. But to Hancock, being associated professionally with Sid James was starting to become restrictive.

To soften the blow, Galton and Simpson wrote a show for Sid, titled Citizen James.

In some ways, it wouldn’t have been a surprise if the Hancock show had suffered as a result of the changes, but some of the most memorable episodes appeared in the final season, including The Blood Donor.

In June 1961, Ray Galton and Alan Simpson finally placed their pens on the table, gave their trusty old typewriter a break and waved goodbye to Anthony Aloysius Hancock, a productive seven-year friendship spawning more than 160 episodes.

While Tony Hancock moved on to other TV shows and films before his tragic death, Ray Galton and Alan Simpson scored another huge hit in the form of Steptoe And Son.

Four series of the father-and-son rag and bone business were transmitted by the BBC between 1962-65. A second run, recorded in colour, screened from 1970-74.

The thrust of the comedy came from the conflict between the father, played by Wilfrid Brambell, and son, Harry H Corbett.

The idea for Steptoe was conceived when the writers penned a Galton and Simpson Comedy Playhouse series.

One instalment, titled The Offer, involved a two-hander between father and son, set in one room. The one-set format was driven, in part, by the fact earlier shows in the Playhouse series had cost too much so they were forced to tighten the purse strings.

A favourable audience reaction and positive response from BBC bosses meant a series – renamed Steptoe And Son – was commissioned. At its peak, the sitcom was watched by more than 28 million.

Alan Simpson retired from scriptwriting in the late 1970s to focus on other business interests while Galton continued writing.

He frequently teamed up with Johnny Speight – famous for Till Death Us Do Part.

Galton also contributed to sitcoms in Germany and Scandinavia. His last situation comedy, working with John Antrobus, was 1997’s Get Well Soon.

But nothing reached the heights of Hancock’s Half Hour and Steptoe and Son, classics for which they’ll always be remembered.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Alan Davidson/Shutterstock

© Alan Davidson/Shutterstock © Allstar/BBC

© Allstar/BBC