It is “The Forgotten Dunkirk” but this week the heroes of St Valery will be remembered.

Just days after the great sea evacuation, the fierce five-day battle of St Valery-en-Caux, ended with the capture of 10,000 soldiers of the 51st Highland Division, left behind as their comrades were ferried to safety from beaches along the coast of northern France.

On Friday, the 80th anniversary, their sacrifice will be marked when, at exactly 10am, hundreds of pipers from around the world will play The Heroes Of St Valery, penned by piper Donald MacLean from Lewis, who was captured at St Valery.

Here, before the tribute – organised by Legion Scotland, Poppyscotland and RCET: Scotland’s Armed Forces children’s charity – Neil McLennan, a historian at Aberdeen University, tells SALLY McDONALD about why the “Forgotten 51st” should always be remembered.

From January 1940, 51st Highland Division soldiers from across Scotland and the UK stood alongside their French allies to defend Europe but they had no idea how quickly the Maginot Line defences would be rendered useless.

Hitler’s “Blitzkrieg” attack, using superior air power and tanks, overwhelmed Belgium, Holland and France and no one seemed able to contain the march of tyranny. In May 1940, with Britain’s back against the wall, Winston Churchill assumed office. German forces pushed hard towards the French coast. The British Expeditionary Force were pushed back to Dunkirk. From there the famous evacuation ensured Britain could live and fight another day. Overall, things looked grim. However, Churchill held out for victory.

A division of the British Army had been severed from the British Expeditionary Force. The 51st Highland Division was made up of mainly “Jock” regiments: Seaforths, Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, Black Watch, Gordons, and Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, alongside Lothian & Borders Horse, Royal Scots Fusiliers, Norfolks, Northumbrians and Princess Louise’s Kensington Regiment with supporting arms and services.

Together they formed a unit of about 20,000 men. Led by General Victor Fortune, they came under overall command of the French to try to shore up their resolve. Memoirs show Churchill’s invidious position. British forces were retreating and Britain’s only ally, France, called out for more reinforcements.

Despite heroic efforts around Abbeville, British troops were pushed further and further back. Preparations were made for another Dunkirk-style evacuation to take place a week after the first. But, until the Navy arrived, a defensive box was formed around St Valery-en-Caux. It was a small harbour town and very different to the previous evacuation. Whilst 3,200 Highland men and some French did escape from nearby Veules-les-Roses, 200 ships struggled to get into St Valery. Fog and German artillery made it impossible.

St Valery burned all around Britain’s young soldiers, many of whom had run out of ammunition.

As the position became increasingly desperate, French forces surrendered. But the Highland Division held fast, with General Fortune calling for white flags to be taken down. While the German army pursued its attack, it was also vulnerable as supply chains were overstretched and the general hoped this might allow his troops to evade their clutches.

But fortune did not favour the brave. The Highland Division had no way of escaping or even meeting the might of German General Erwin Rommel’s Panzer Divisions. Their rifles were futile against the enemy’s heavy armour. And, at 10am on June 12 – after several days of intense fighting – General Fortune made his most difficult decision; to surrender. One thousand men died and 4,000 were injured.

Fortune and his men were marched from France to prisoner-of-war camps in Eastern Europe. There were a small number of escapes, but 8,000 men were led off as PoWs. They were interred for the remainder of the war. Many ended up in brutal salt mines as forced labour on limited food rations.

The event was a catastrophe. Churchill called it the “most brutal disaster” we had yet suffered. Speaking in Aberdeen in 1946, he also mentioned the Highland Division to resounding cheers. And General Charles De Gaulle – later to become French president – said in a 1942 speech in Edinburgh: “The valiant 51st Highland Division played its part in the decision which I took to continue fighting on the side of the Allies until the end no matter what may be.” By 1945 the newly reformed Highland Division re-entered St Valery, this time to liberate it. Led by pipers, the war was slowly but surely being won.

St Valery 1940 made its mark on many. Scottish poet and war writer Eric Linklater said: “To Scotland the news came like another Flodden.” And historian of the 51st Division, Brigadier Charles Grant concluded: “There can hardly have been a town, village or hamlet in the Highlands which was not directly affected by the loss.”

Donald Smith, fought with the 51st Division. He was taken prisoner and held at Stalag VIII-B Lamsdorf in Poland before being part of the notorious, four-month, 1,000-mile-long “death march” that saw PoWs forced west on foot away from the advance of the Allies. One in four died before they were liberated by the Americans.

The friends Donald lost in the “forgotten Dunkirk” are buried in the cemetery at St Valery. He has visited their graves. And, despite his advanced years, youthful Donald tries to make it to London’s Cenotaph in November to remember other fallen comrades.

Yorkshire-born Donald, who has three grown-up children, two grandchildren and two great-grandchildren, said: “I could not have believed back then that I would be looking forward to my 100th birthday. It doesn’t feel like 80 years ago. I can never forget.

“The Heroes Of St Valery piping event is a great way to pay tribute to the boys that were left behind. It’s wonderful they are remembered in this way. I feel proud. It makes my day to hear the pipers.”

We didn’t know about Dunkirk… no-one told us

Great-grandad Donald Smith was a member of the ill-fated 51st Division ordered to fight on by Winston Churchill after Dunkirk.

The veteran, who marks his 100th birthday in October, remembers the events of 80 years ago as if they happened yesterday.

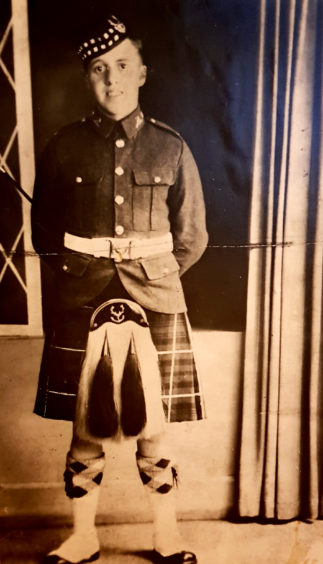

Donald – who lives in Forres, Morayshire, with his wife Helen, 85 – joined the Territorial Army aged 16, before, in 1938, signing up with the Seaforth Highlanders. A year later, during training at Fort George near Inverness, he took a picture of himself with five friends. He was the only one of them to survive.

Reliving the Battle of St Valery-en-Caux, the ex-soldier, who was just 19 at the time and had already lost pals at Abbeville, said: “We didn’t know anything about Dunkirk. They never told us about it.

“We finished up holding the perimeter of St Valery at Veules-les-Roses. It was a big, open space and we had no time to dig in. We saw the German army coming across the fields, soldiers in front, the tanks coming behind. We were lying on the ground, facing them, and leaning over our packs with our rifles. We managed to stop them but that’s when the big guns opened up. We were facing heavy weaponry with small arms. It was a hellish scene. The whole place was on fire. We thought that was the end.

“I was on the Bren gun and the magazine went empty. I lifted my hand to take it off and put a new mag on when a shell burst over us. All I felt was a bang. It knocked my hand right back, took a finger off, and cracked my head. I couldn’t remember anything much after that. My friends Nobby Clark and Bernard Finn were either side of me. They were killed outright.

“You don’t have time to feel fear. All you are thinking about is staying alive and, as bad as it sounds, killing that German in front of you.”

He was severely wounded but managed to make his way to the town of St Valery, where he passed out from blood loss and was captured by the Germans.

He and other prisoners were frogmarched along the top of the cliffs where they could see the boats out in the Channel. He said: “There was a big German officer who asked how old I was. I was in a state, but I managed to say, ‘I’m old enough to fight you’. He just smiled at me and said in perfect English, ‘for you the war is over’.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Northcliffe Collection/ANL/Shutterstock

© Northcliffe Collection/ANL/Shutterstock