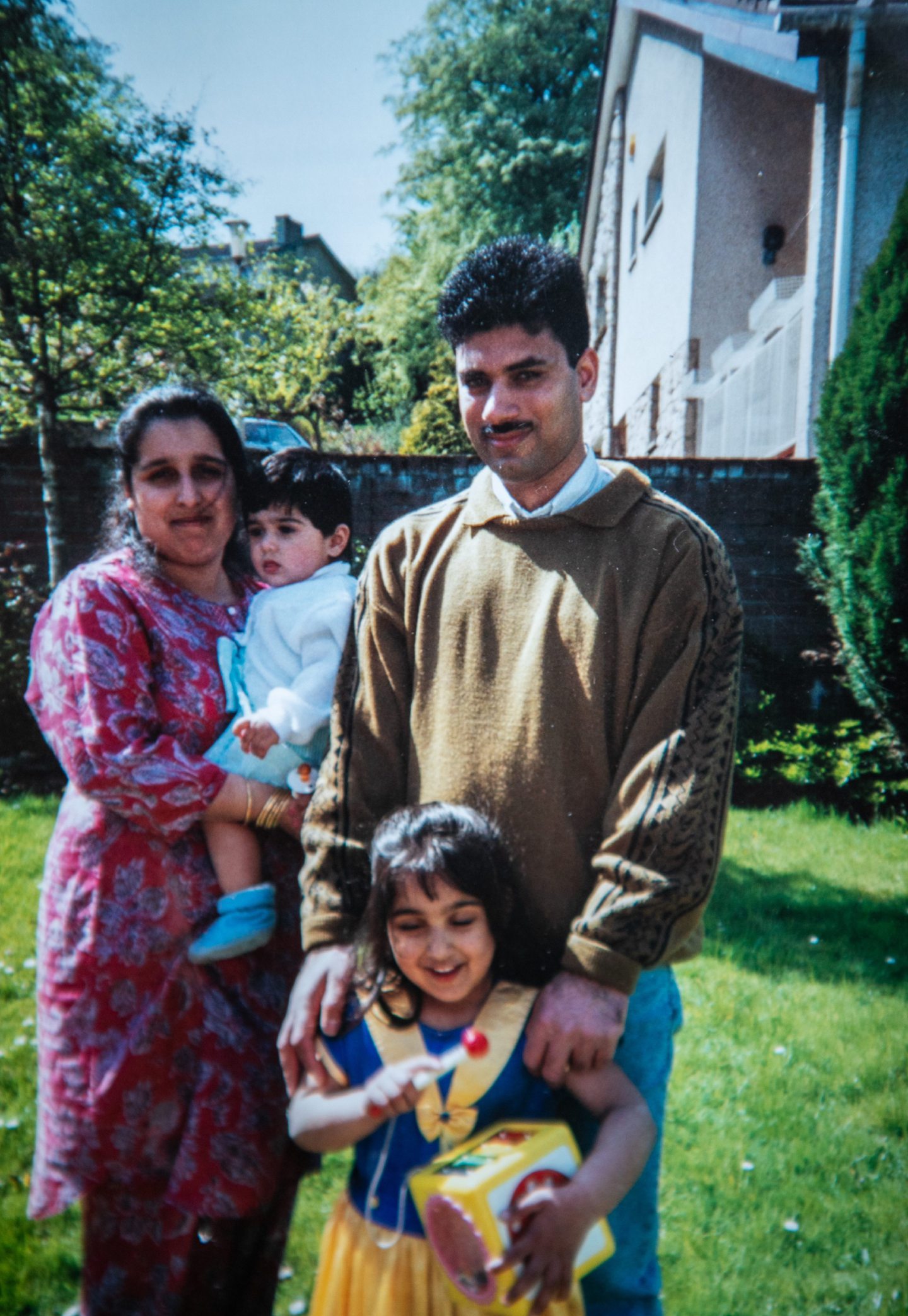

Comedy writer Amna Saleem, 31, is celebrating her sitcom debuting on BBC Radio 4. While her Scottish and Pakistani mash-up, Beta Female, is played for laughs, here she describes how cultural expectations could mean her relationship with parents Saleem and Yasmin was sometimes fraught as she grew up in Motherwell but how her writing career has now brought them closer than ever.

My childhood home was stacked high with books, trips to the library were a weekly treat and the news blared in the background at all times. Yet it seemed to be a complete shock to my parents to discover they had raised a creative young woman with opinions of her own.

My parents were an enigma to me, growing up. My dad was born in Pakistan and found it difficult to release the patriarchal values that were instilled in him. My mum was born in the UK, as were my siblings and I, so she was a little more understanding but ultimately her values aligned with my dad’s. They seemed to exist in a state of cognitive dissonance where they felt they had to behave one way while clearly holding opposing opinions.

My life was a long list of things I wasn’t allowed to do. Hearing the word “yes” was a rare occurrence. What others might think of us was always more important to them than what I thought and I deeply resented their ability to commit to the will of the Asian community but not their children.

At 18, in a misguided and impulsive act of rebellion, I moved to Paris where I found a part-time job to fund my expensive literature habit. A few weeks before, my parents had successfully guilted me out of attending film school and the frustration that had been mounting inside as I yearned for my own autonomy forced me to take action.

It didn’t help that while I loved Glasgow, I was exhausted from trying to fit in. I was constantly being accused of being too brown for my white peers and too white for my brown ones. It just felt easier to be a foreigner in a new city than to be treated like one in my own.

The summer before last, I reluctantly returned home after becoming severely unwell with the intention of only staying for three months while I put myself back together. It was the last place I wanted to be. As I recovered and the worst of my depression lifted, I began to notice things with fresh eyes. I was able to see my parents as people more clearly than I ever had before. Slowly, forgiveness took the place of anger, as I witnessed all the tiny ways in which they had grown and changed. Their unexpected admission that it was the constant challenge of having four bright, kind, well-rounded children that had encouraged them to open their minds was startling.

Later, dad came to understand he had lived his life in a way that deprived him of emotionally connecting with his children. That admission was brave but difficult for him and he fell into a depression of his own, which led to me finding him a therapist.

It was the first time in my life where I had savings which meant I could finance his sessions, allowing him to focus solely on getting better. It was to be the best investment I ever made.

My parents were adorably excited when they heard my sitcom Beta Female was being aired on Radio 4. I accidentally overheard them bragging about it on the phone to relatives which is where all the real unfiltered information is shared. It was nice to know they were proud, especially as it was only a year ago that they were hopelessly praying for me to “find a real job”.

It’s ironic that my biggest detractors became my inspiration. Throughout the course of the last few years, I had unwittingly turned my parents into recurring characters on my Twitter account where I would joke or make wry observations about them and our Scottish-Pakistani lives.

Most of the time, it’s an innocuous existence but every so often the juxtaposition of both cultures gave me fun anecdotes to share on my platform. Many readers could see their own idiosyncratic families reflected in my posts and others were purely entertained by the little glimpses into my colourful life. It was a fun distraction from my job as a receptionist in London where I had moved in hopes of achieving my goal of becoming a writer.

In fact, my tweets were the small seeds from which my sitcom grew. It’s where award-winning producer, Ed Morrish, took note of my comedy chops. He wondered if I could take my anecdotes and weave them into a pitch for BBC Radio. I did, and it culminated in the BBC commissioning a pilot, which aired in 2019, and eventually led to a full season order which started this month.

It’s been an unexpected but exciting journey. The week after the pilot aired, a self-described “old white man” emailed to let me know how much he’d really enjoyed Beta Female.

He confessed that he had actually intended to switch it off on hearing the introduction but his dog had distracted him and he found himself laughing at a show he had been convinced only five minutes before wasn’t for him. He said that he’d been shocked to find it so relatable, which made me chuckle as there are few things more universal than family drama.

A few days later, a lovely British-Indian woman got in touch to tell me about all the ways she had felt. It made me tear up. After years of being told by industry professionals that my writing was too niche for public consumption, I suddenly had more than enough evidence to stop believing them.

Sky sponsored me to write a TV draft of the pilot which would subsequently be showcased as a live table read.

I ended up acting in my own work alongside a wonderful cast which included my childhood icon, Nina Wadia, to an audience of TV executives and peers. I was highly anxious but I needn’t have been as everyone laughed exuberantly throughout. I remember wishing it was possible to capture the sound in a bottle to keep forever. Afterwards, instead of celebrating, I found myself making excuses to hide in the bathroom to cry. There were many friendly and supportive faces in the crowd, but all I could see was the absence of my family.

In their defence, I hadn’t outright invited them to the live reading in London. I had dropped hints, hoping that on the day I’d look out into the audience and see them cheering me on but I didn’t ask and they didn’t come.

It was our status quo. Our relationship had been strained for almost a decade and I guess I turned that pain into humour to protect myself. They had wanted the good Asian daughter who did what she was told and never asked questions but all I had were questions. My curious and creative nature appeared to be something that needed to be extinguished rather than embraced.

If someone had told me that by the time Beta Female returned for its debut series my dad would be one of my biggest fans, I’d have filed the claim under science fiction as only a radioactive meteor shower could be responsible for such a drastic change.

In fact, it’s all turned out much stranger than fiction. After long-held disdain over my choice of career, my dad has asked I write him a role in my first TV project. He now fancies himself an actor.

Beta Female, Radio Four, Tuesday, 6.30pm. The pilot episode can be heard on BBC Sounds

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley