Asterix co-creator Albert Uderzo, who brought the heroic Gaul to life in books that have sold millions of copies worldwide, died earlier this week at the age of 92.

Here, Glasgow University Professor of French and Text/Image Studies Laurence Grove tells Ross Crae The Honest Truth about the French illustrator and his iconic character.

How important was Uderzo’s work, and what is his legacy?

I would say he helped make comics what they are today. Comics nowadays have taken on the status of cinema, and that wouldn’t have been possible without Albert Uderzo.

To a certain extent, you could say Asterix has changed the comic strip world because, when it first appeared in 1959, comics were for kids. As Asterix grew older so did comics.

One of the interesting points is that, when Uderzo retired in 2011, Didier Conrad who did the drawing for the later albums wanted to imitate him. He didn’t want to put his own mark on it at all, he wanted to make it as much like Uderzo as possible.

How iconic a character is Asterix?

For many, Asterix symbolises France itself. When France had a space programme, they named the rocket after him. When they first won the World Cup, the team was compared to having the Asterix buzz to them, that they were the little ones who beat the big ones.

You can also see the history of France through the Asterix albums from 1959 and all the external politics right through to things like the crash of the Berlin Wall.

Why do his adventures have such enduring popularity?

In a similar way to so much of culture, such as the likes of James Bond and Indiana Jones, Asterix has a formula which will always work.

It adapts to individual stories and to the time. It keeps certain pillars that will anchor people in, then it will give you something specific related to what’s going on.

In the swinging sixties, there were references to The Beatles, when it was the American bicentenary they went to what is now New York. In one of the recent albums, there were references to tweeting, and the last one had a female teenager taking up the needs of the planet.

It’s the mixture of the eternal and the specific, all of which is hidden behind anachronisms, the Roman setting and a lot of clever wordplay.

How does he compare to another comic hero, Tintin?

In some ways he’s the opposite of him – Tintin is the adventure hero and Asterix is more the intellectual hero. Tintin is derring-do, Asterix is comedy and slapstick more or less.

Asterix is French and Tintin is Belgian so the two of them form opposites which complement and contrast each other.

What are Asterix’s Scottish connections?

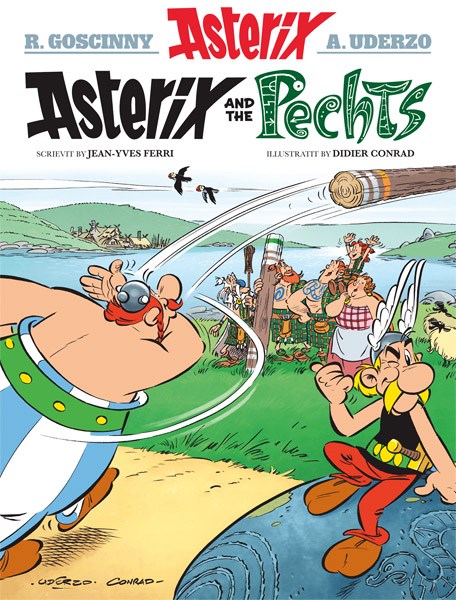

2013’s Asterix and the Picts saw him visit Scotland – or Caledonia as it’s called in the book. It was the first story that wasn’t by René Goscinny and Uderzo, although Uderzo did oversee it.

The new author was a big fan of Scotland, and the Asterix tradition has always been to have a home adventure and an away adventure and so on. For the first one he felt that Scotland was the country which Asterix should have always gone to but never had.

Education Scotland have since used Asterix and the Picts in the curriculum for excellence as a work to improve language skills and social knowledge of France.

The writer, Jean Yves-Ferri, said at the time that the natural landscape of Scotland was a perfect setting, but how did the political landscape also shape the story?

Asterix and the Picts was partly about the 2014 referendum. Scotland was in the news at the time because of it.

Yves-Ferri came to Glasgow for a conference and launched the book there, and he was very clear that it had a pro-independence leaning to it. That was certainly his view and there are one or two hints in the book.

The story is about various clans of Scotland coming together against a common enemy. You can read into that what you like!

Asterix and the Pechts

The 2013 book was the first to be translated into Scots. The adventure saw Asterix and Obelix find a Pict washed up on the Gaulish shores.

They help the warrior, named MacHoolet, return home to win back his kingdom – and the heart of his favourite lassie, Camomilla.

Asterix and Obelix meet Nechtan, an ancestor of the Loch Ness Monster, lots of other Pechts with names like MacSixtiwatt and MacMeboak and, of course, encounter some Romans along the way.

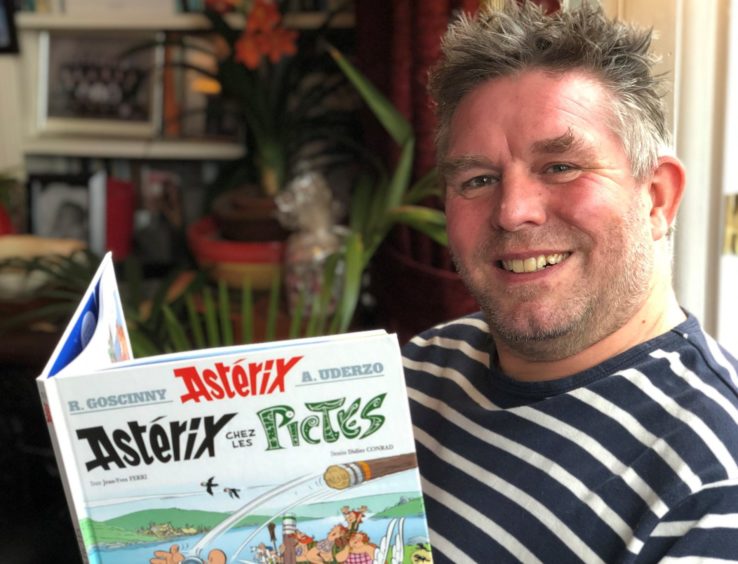

The book was translated into Scots by writer Matthew Fitt.

“I read Asterix when I was a bairn in Dundee libraries,” he recalls. “I thought I was having a skive reading a comic book.

“But I learned more about writing and storytelling and world history from Asterix books than from many of the other books I was meant to be reading.

“It’s the little guy sticking to The Man. Asterix is William Wallace, Spartacus, Joan of Arc, and Katniss Everdeen rolled into one. And it’s funny, laugh out loud funny.”

He joined Prof. Grove in hailing the influence of Albert Uderzo.

“Just say the name Obelix and you see him without going near a book or picture of the character. Albert Uderzo did that,” he says.

“His world class artwork made Asterix known and loved around the planet.”

Matthew says he was ‘over the moon’ to be asked to translate the series into Scots, of which he is a proud speaker.

“Going from reading Asterix in the Wellgate Library to becoming an official translator of the series was something I could never have imagined happening.

“I’ve translated eight volumes into Scots and have laughed my way through every page. Every line Rene Goscinny wrote is a joke, every plot is a cairry-on.”

Matthew was ‘affy chuffed’ when Asterix finally made it to Scotland.

“I got Asterix and Obelix speaking Glaswegian and the Picts coming from the North East had to be Doric speakers,” he says.

“In honour of the great metropolis situated on the north bank of the Tay, I made the Romans in this episode speakers of the best Scots dialect ever, Dundonian.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe