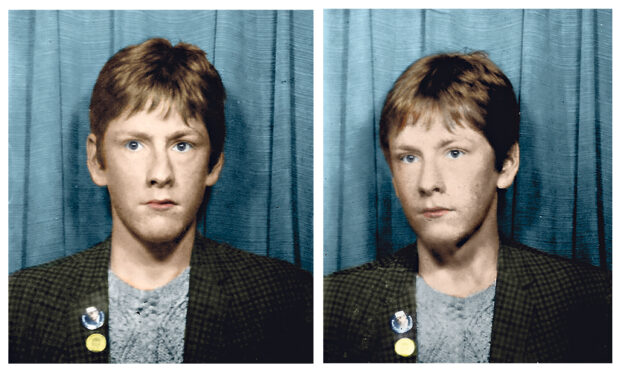

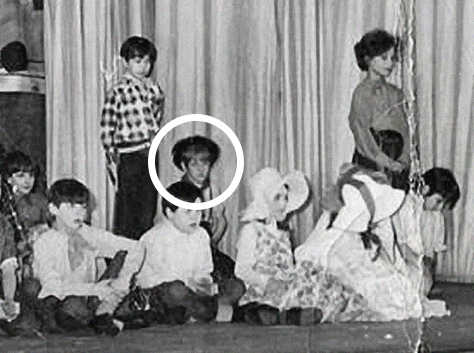

My awkward relationship with music is captured in two school photos. The pictures are from musical shows. These were collaborative efforts when the classes of North Berwick Primary (now Law Primary) would perform to parents in the hall of the high school.

These events were such a rip in the fabric of normal life that I have no trouble remembering them. In one of the pictures, my class is dressed as Ken Dodd’s Diddymen. As most of us were short and thin and the Diddymen were squat and fat, an element of padding was required.

My mum helped out by sewing some strapping on to a cushion, which was stuffed inside a waistcoat while I hid my embarrassment under a rakish top hat. In the picture, with the class spread out across the stage during a chorus of We Are The Diddymen, I look like a cross between the Artful Dodger and Johnny Rotten, albeit fatter than either.

The second show has a Wild West theme. I am happier with my hat in this picture – a Stetson with decorative tassels – but the image does prompt a blush of embarrassment. For the big musical number in this show the class was divided into horses and riders, with the more mature kids getting to embrace their inner bucking bronco, and the smaller kids playing the cowboys.

Obviously, as my physique made the Milky Bar Kid look like John Wayne, I was a cowpoke. I don’t remember exactly how it happened, but I do know that I was bucked on to the top of the piano where I lay for a moment, floating in airless humiliation as the music teacher belted out the saloon bar boogie woogie in the style of a rusty pianola from 1928.

As a shy child, public performances didn’t come naturally. As a shy child from the east coast of Scotland, I had an in-built understanding that reticence was the supreme virtue, as important as wearing clean underpants in case of accidental death on a pelican crossing, or having a bath once a week whether you needed it or not. How shy was I? Well, hiding it wasn’t difficult. I was pretty good at being invisible. And I do remember spending an evening concealed beneath a piano during a social evening with teachers on a school trip to Glen More. If my presence was missed, nobody mentioned it.

But shyness is relative. Long after school, I found myself sitting next to Dolly Parton in her Tennessee theme park, Dollywood. Dolly in the flesh is everything you would hope her to be. She is both smaller and larger than you might expect. She is glamorous and trashy, brazen and entirely unapologetic. So I asked her, only half in jest: have you always been this shy and retiring?

She dissolved into laughter and touched my arm. “Actually,” she said, “when I was little I was always kind of hyper. I had a lot of energy but I was kind of bashful of strangers. I know that sounds funny, saying that I was ever shy or bashful, but there are times even now where I’ll find myself feeling very shy.”

There is, of course, only one Dolly Parton, but it’s not unreasonable to suggest that her greatest creation is her public image, an overstated cartoon which is so irresistible that it allows her to hide in plain sight. What do we know about the real Dolly Parton? Roughly the same as we know about her dutiful husband Carl.

My own journey out of shyness also involved music, but a less flamboyant dress code. At school, music was a dead subject. We sang Marie’s Wedding and The Banana Boat Song for approximately 12 years, during which time I failed to grasp the simple principle that singing involved going higher and lower rather than just hovering in the uncertain space between quiet and inaudible.

In the auditions for the school show, Salad Days, the music teacher stood the class in a line while she assessed our singing voices. My good friend Kendo was praised for his beautiful tenor, and then the music teacher’s ear hovered in front of me. The decision was made at lightning speed. I was assigned a role in the chorus and encouraged to sing silently. Opening my mouth was OK. Making a noise was not.

And then, punk rock happened. It wasn’t an instant thing. Information arrived slowly, via the music papers and late night radio. There weren’t many shows to go to. But Edinburgh had a trail of record shops, from Bruce’s to Hell, Hot Licks to Ezy Ryder and the Other Record Shop. As punk records started to emerge, the Melody Centre in North Berwick displayed the sleeves around the window, with the Sex Pistols’ God Save The Queen facing backwards to minimise offence.

Encouraged by home-made magazines such as Sniffin’ Glue, which came direct from London, Grangemouth’s The Next Big Thing, and Edinburgh’s Jungleland (an early outlet for Mike Scott, later to find fame with The Waterboys) I planned my own fanzine, originally to be called Fish Pie Talks, but later settling on Alternatives To Valium, after a headline in The Sunday Post.

The idea of punk was that anyone could do it, and this applied to making music and writing about it. I had a go at singing, though my music teacher would have balked at that description, and writing, which needed nothing more than willpower. Once, at a reading by James Kelman, the author was asked what it took to become a writer. “A pen and paper,” he replied. He wasn’t being a punk – this was years later – but the attitude was correct. I wrote. It was easier than talking. I wrote letters encouraging musicians to explain their art. I wrote to Mike Scott, and he replied, giving me his views of Yoko Ono. Colin Vearncombe of the Liverpool band Black (later to have a worldwide hit with Wonderful Life) wrote back, adding a bit of pluck to the punk DIY attitude. “Write your own bloody Bibles!” he suggested.

Mark E Smith of The Fall sent a page from Titbits magazine which had inspired one of his songs. I blagged my way into the screening of the BBC arts programme Riverside, where The Cure were collaborating with some ballet dancers. In the bar, I forced myself to approach their singer Robert Smith, who told me that The Cure, as a band, was finished. These were slower times – the internet didn’t exist – so I sat on my scoop for several months, by which time Smith had changed his mind.

The more I talked, the easier it got. Interviewing is a good occupation for a shy person. You have permission to speak, and you know how to listen. Sometimes these rules don’t hold, and something uncontrollable happens, but if you can stand your ground and find a reply, something good can come out of it. That, at least, is what I told myself when Shane MacGowan of The Pogues started off by asking what religion I was, and when I said none, he replied testily, “Only a Protestant would say that” (I paraphrase slightly). Similarly, there was an element of chaos when I summoned all my energy during a press conference for the pro-Labour Party Red Wedge tour to ask Paul Weller about the price of tickets. I was trying to ask something more complicated, but I was lucky to get away without a nosebleed.

One of my favourite interviews was one in which I had almost no control, but a surprising amount of access. Rod Stewart was in Glasgow for a cup final at Celtic Park, and the pre-match lunch at One Devonshire Gardens involved liberal quantities of brandy, and a conga through the hotel of the LA Exiles football team, led by Rod, with his brother trailing along with an upturned laundry basket on his head.

The interview was supposed to continue on the bus from the West End of Glasgow to the east, but Rod had grown weary of answering questions and started singing instead. He ran through Me and My Shadow, Irving Berlin’s When I Leave The World Behind (which tells of a millionaire burdened down by care), Strolling by Flanagan and Allen, Swanee by George Gershwin. There was no need to interrupt. The music said it all.

Sound & vision

From a disgraced singer to a Hollywood legend via The King and a dreamy, atmospheric movie, Alastair McKay shares the music, films and TV shows that have shaped his life

The first record you bought

I’m The Leader Of The Gang (I Am) by Gary Glitter. This is an embarrassment now but it did the trick at the time. I was the runner-up in a Gary Glitter impersonation contest at a disco for the Gullane Under-14s football team. I won 50p and a lifetime of regret.

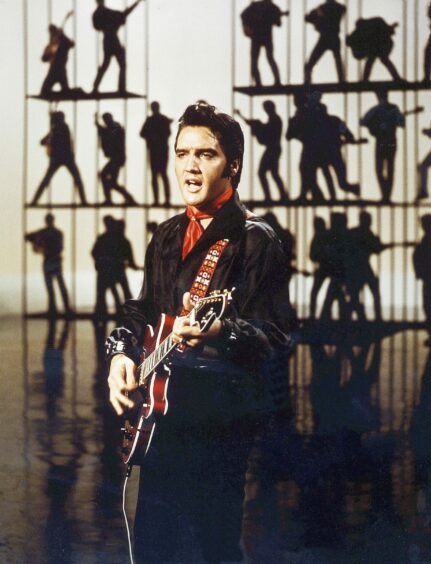

Who is your music hero?

It flickers between Elvis Presley, Hank Williams and Lou Reed. Elvis did everything first and is still almost unbelievable. Hank brought light to the darkness. Lou created his own world.

What is your favourite song?

It changes all the time, but very often it is Party Fears Two by The Associates. It remains amazing that Billy Mackenzie and Alan Rankine managed to make an irresistible pop record from a song about social dread. Also, Gillian Welch’s Elvis Presley Blues is wonderful.

What was your first gig?

Slade at Leith Citadel. It was the best concert I ever went to, even though I got mugged by skinheads on the streets of Leith. For a while, Slade had everything. Their later ballads are the template for Oasis, but we needn’t hold that against them.

What is your favourite film?

Paris, Texas by director Wim Wenders. It’s so beautifully atmospheric. It has a great soundtrack by Ry Cooder and cinematography by Robby Müller which gives it the quality of a dream. Plus, Nastassja Kinski. I love all the Wim Wenders films from that period. But it’s also worth mentioning Bill Forsyth’s Gregory’s Girl, which was an absolute inspiration.

Favourite TV show?

Recently, it would have to be Succession, especially the first two series when there was still the possibility that some of the characters had redeeming features. Brian Cox is always great, and he did a series of independent films building up to Succession which someone should gather together in a cinema season.

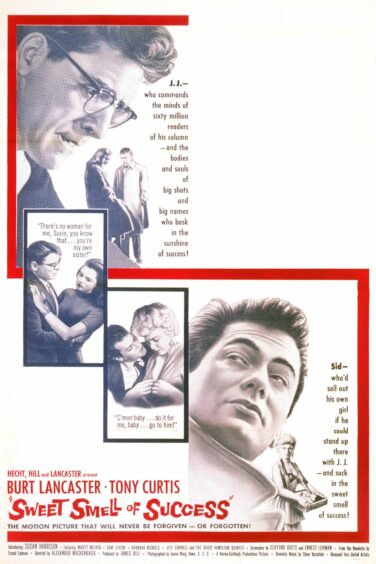

Who is your favourite actor?

Burt Lancaster. He always seems slightly larger than the films he is in, and he has such presence that you forget he is acting. My favourite performances of his are in The Swimmer (1968) and 1957’s Sweet Smell Of Success but I often think about the populist preacher he plays in Elmer Gantry. He’d do well in today’s politics.

Alternatives To Valium: How Punk Rock Saved A Shy Boy’s Life by Alastair McKay, is published by Polygon on Thursday

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© SYSTEM

© SYSTEM